The Real Mars Lander in 'The Martian': Fact Checking the Film's NASA Probe

A historic NASA spacecraft makes more than just a cameo appearance in "The Martian," the new Ridley Scott movie about an astronaut stranded on Mars.

The 20th Century Fox film, which opened in U.S. theaters on Friday (Oct. 2), follows NASA's third crewed mission to land on the Red Planet in 2035. By the movie's timeline, Ares 3 crew member Mark Watney (Matt Damon) walks on Mars 23 years after the space agency's most recent real-life "martian," the robotic rover Curiosity, arrived to search for environments habitable to supporting past and present life.

But it's not Curiosity that is in "The Martian." (Spoiler alert: the following contains plot details from the movie.) ["The Martian" and NASA: Full Coverage]

Rather, it is NASA's first Mars rover, and more specifically its three-petal lander, that Watney uses to contact Earth.

Mars Pathfinder and its small, six-wheeled Sojourner rover touched down on Mars on July 4, 1997. For almost three months, the lander beamed back billions of bits of data, including tens of thousands of images, before it fell silent. The science gathered by the lander and rover suggested that Mars was warm and wet in its past, a finding that was confirmed by later NASA missions, including Curiosity.

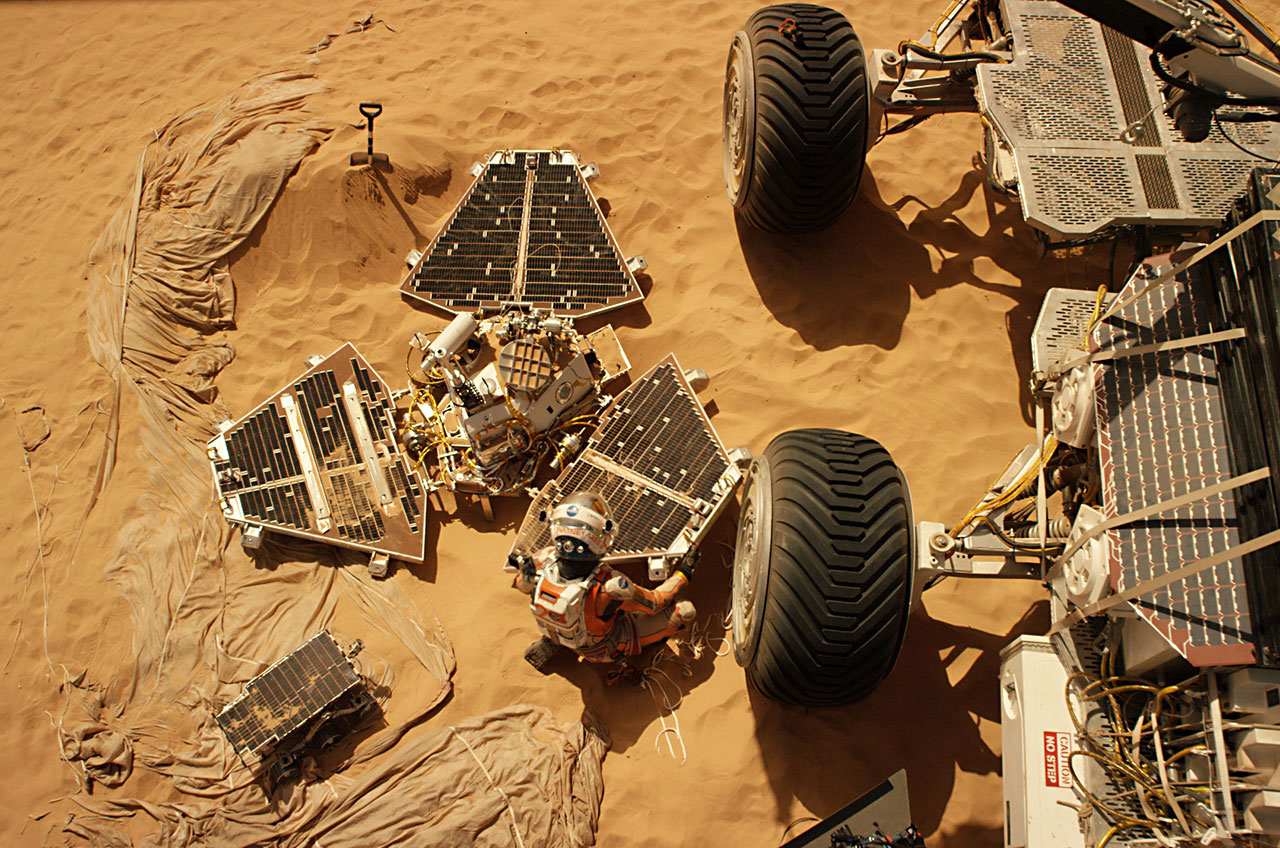

In "The Martian," Watney sets out to retrieve Pathfinder to use its radio and camera to re-establish communications with NASA after his own habitat's antenna is destroyed in a dust storm. The filmmakers consulted with engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) before recreating the probe for the film.

"They were helpful with drawings and technical information about how that worked and the components, which we had to replicate," described production designer Arthur Max in a video released by the studio. "We have a fully practical working Pathfinder, which we use throughout the movie."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ready for its close-up

"[It] looked pretty good to me," said Donna Shirley, who in 1997 was NASA's Mars Exploration program manager. ["The Martian": A Movie and Book Review]

collectSPACE.com asked Shirley and Rob Manning, who was Pathfinder's chief engineer, to help fact check the movie's version of the spacecraft that they designed and helped to oversee on Mars.

"It looks like they got close," said Manning. (Both he and Shirley had yet to view "The Martian," but commented for this article based on studio-released stills and descriptions shared by collectSPACE.)

There were some differences in the details. For example, the film's version of the Pathfinder lander is equipped with LED status lights.

"Nope, no LEDs," Manning confirmed. "That would have been cool. We did talk about that possibility back then but LEDs were hard to qualify for the Mars environment."

And then there's how Pathfinder first appears in the movie when Watney arrives at its landing site — the lander and rover are completely buried in the sand. Thirty-eight years later, would the lander be covered?

"While we don't have many decades of observation of the dust storm conditions, we can say from observations at the landing sites and observations so far that it is unlikely at the relatively short time scale between 1997 and 2035 that a significant fall out of dust could accumulate in such a short time," said Manning. "However it's not impossible."

Powering up Pathfinder

Appearance aside, "The Martian" relies on how Pathfinder was designed in order to allow Watney to trade messages with Mission Control. After moving the lander to the Ares 3 hab, the astronaut sets about rebooting the probe.

"There was no accessible power plug or power connector other than the solar panel connectors" Manning said. "The power to the lander while cruising to Mars would come in through the top of the lander, [but] that becomes unusable on Mars because the lander opens up relays to prevent those wires from shorting during landing and while on [the surface]."

Even if Pathfinder had a spare port by which to plug in an external power source, as is shown in the film, it may not have done much good.

"Remember, we think Pathfinder died because something inside it broke," Manning explained.

After about its 40th day (sol) on Mars, the lander's battery no longer held a charge, so from that point forward, it shut off before sunset and woke up with the sun.

"At night, without a battery, it got really chilly inside the lander, and we think that the electronics got too cold and something inside broke," Manning said. "If someone came along and put 30 volts on the lander's solar array cables that went into the lander, [Pathfinder] would probably not wake up."

"On the other hand, there were failure mode possibilities where a solid external 30 volts supply may have been able to overcome the fault and the lander computer might have booted," he added.

Smile for the camera

To communicate with NASA, Watney manually points the lander's high gain antenna towards Earth (something only possible if he unbolted it first, Manning said) and then sets up three signs around the Pathfinder in view of its mast-mounted revolving camera. On the middle sign, he writes a question ("Are you receiving me?") and on either side are signs that read "Yes" and "No." [Surviving "The Martian": How to Not Die on Mars]

To respond, NASA sends a signal to point the camera at the "Yes" sign.

"This was quite a good idea," said Manning. [The] camera could be aimed within a degree or so in both azimuth and elevation."

In order to allow more complex questions, Watney figures out he can arrange even more signs at intervals around the lander so NASA can spell out its replies using ASCII in hexadecimal code. The flight controllers catch on and the camera pivots between the signs in quick fashion.

Manning thought this too would be possible, although at a slower pace (minutes rather than seconds) than is shown in the film.

Ultimately, NASA conveys the instructions to Watney on how to reprogram Pathfinder such that it can be plugged into the astronaut's rover, enabling longer text messages to be transmitted. Unlike the problem of the missing power port, establishing the comm connection might be feasible.

"There is a spare RS-422 [serial interface] port directly into the flight computer that we used to give us access to the flight software and low level commands while it was still here on Earth," noted Manning.

Continue reading at collectSPACE about Mars Pathfinder's fate in real life and how it may compare to "The Martian."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.