Nobel Prize in Physics Honors Flavor-Changing Neutrino Discoveries

Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald will share this year's Nobel Prize in physics for helping to reveal that subatomic particles called neutrinos can change from one type to another — a finding that meant these exotic particles have a teensy bit of mass.

Neutrinos are the second-most abundant particles in the cosmos, constantly bombarding Earth. (Photons, or particles of light, are the most numerous.) The tiny particles come in three flavors: electron, muon and tau. In their separate experiments, Kajita and McDonald each showed that neutrinos change between certain flavors — a process called neutrino oscillation.

"The discovery has changed our understanding of the innermost workings of matter and can prove crucial to our view of the universe," representatives of the Nobel Foundation said in a statement about this year's Nobel Prize in physics.

In 1998, Kajita presented research that showed that muon-neutrinos created by reactions between the atmosphere and cosmic rays changed their identities as they traveled to the Super-Kamiokande detector, buried in a zinc mine, about 155 miles (250 kilometers) northwest of Tokyo. [5 Mysterious Particles Lurking Underground]

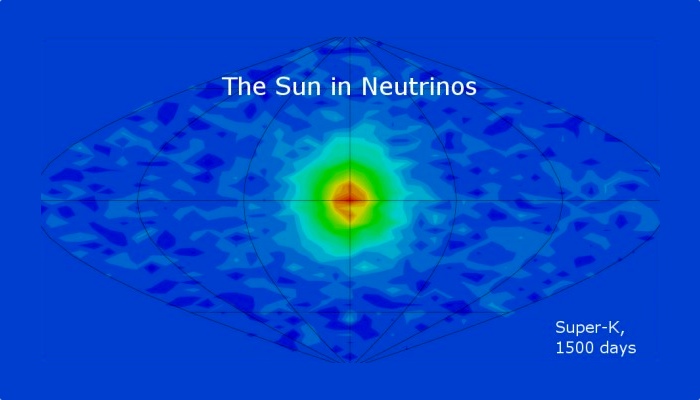

In 2001, McDonald and his team announced that they had discovered that electron-neutrinos from the sun changed flavors into muon- or tau-neutrinos on their way to the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Canada.

Neutrinos very rarely interact with matter; they can zip through a block of lead a light-year across. Large underground detectors, like the ones in Japan and Canada, are needed to observe such rare interactions with matter.

The Nobel Prize-winning discoveries have far-reaching implications, scientists with the Nobel Foundation say. For instance, they could help physicists figure out the matter-antimatter puzzle: Scientists think that during the Big Bang, equal amounts of matter and its weird cousin antimatter were produced; smash-ups with matter destroyed most of this antimatter, leaving a slight excess of matter in the universe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Physicists are still unsure why matter won this cosmic clash. One way to solve the puzzle would be to find matter behaving differently from antimatter; flavor-changing neutrinos could be one way to see this difference.

In addition, neutrinos would not be able to oscillate, or change their identities, if they had zero mass, physicists say. Therefore, the experiments by Kajita and McDonald also uncovered neutrinos' slight mass.

Kajita, like most Nobel Prize winners, was surprised to get the call this morning letting him know of his achievement. When Adam Smith of the official Nobel Prize website asked Kajita if he'd ever dreamed of this moment, he responded, "Well, of course, well, as really a dream, maybe years, but not serious dreaming so far."

Kajita, of the University of Tokyo in Kashiwa, Japan; and McDonald, of Queen's University, in Kingston, Canada, will share the Nobel Prize amount of 8 million Swedish krona (about $960,000).

Yesterday, the Nobel Foundation announced the Prize in physiology or medicine to a trio of scientists for discovering novel treatments for parasitic infections. Tomorrow (Oct. 7), the Nobel Prize in chemistry will be announced.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.