It's officially autumn, and time once again to seek out the two most distant planets of our solar system, Uranus and Neptune.

Both are gas giants and each can be readily identified using good binoculars. Uranus, in fact, can be seen with just your unaided eyes under a dark, clear sky — if you know where to look. Fortunately, both are currently well-placed for viewing in our evening sky and with the waning moon moving into the morning sky, it will be a good time to look for these two faint planets.

Here's an overview of where to spot the distant planets, as well the intriguing histories of their discovery. [October 2015 Skywatching Guide]

Uranus at opposition

Interestingly, although the planet Uranus can be glimpsed with the unaided eye under favorable conditions, its presence was unknown until March 13, 1781, when William Herschel discovered it by accident using a 6-inch reflecting telescope. Herschel initially believed he had discovered a new comet, noting that it was moving slowly through the constellation Gemini. He did not announce the discovery until just over a month after his first observation of the new object.

But after several notable European astronomers calculated its orbit it became clear that Herschel's object was not a comet, but actually a brand-new planet; the very first planet that was discovered scientifically.

Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal of England, asked Herschel to name the new planet and Herschel responded with Georgium Sidus (George's Star), or the "Georgian Planet," in honor of King George III of England.

Unfortunately for Herschel, his proposed name for the new world was not very popular beyond the realm of Great Britain and other possible names were soon put forth: Neptune and Uranus were the two that were most bandied about with Uranus — the primal Greek god personifying the sky — being the most popular. The confusion over what moniker to definitively assign to the seventh planet continued right up through the first half of the 19th century until 1850, when the British Nautical Almanac Office finally switched from Georgium Sidus to Uranus. That's when the name finally stuck. [Photos of Uranus, the Tilted Giant Planet]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

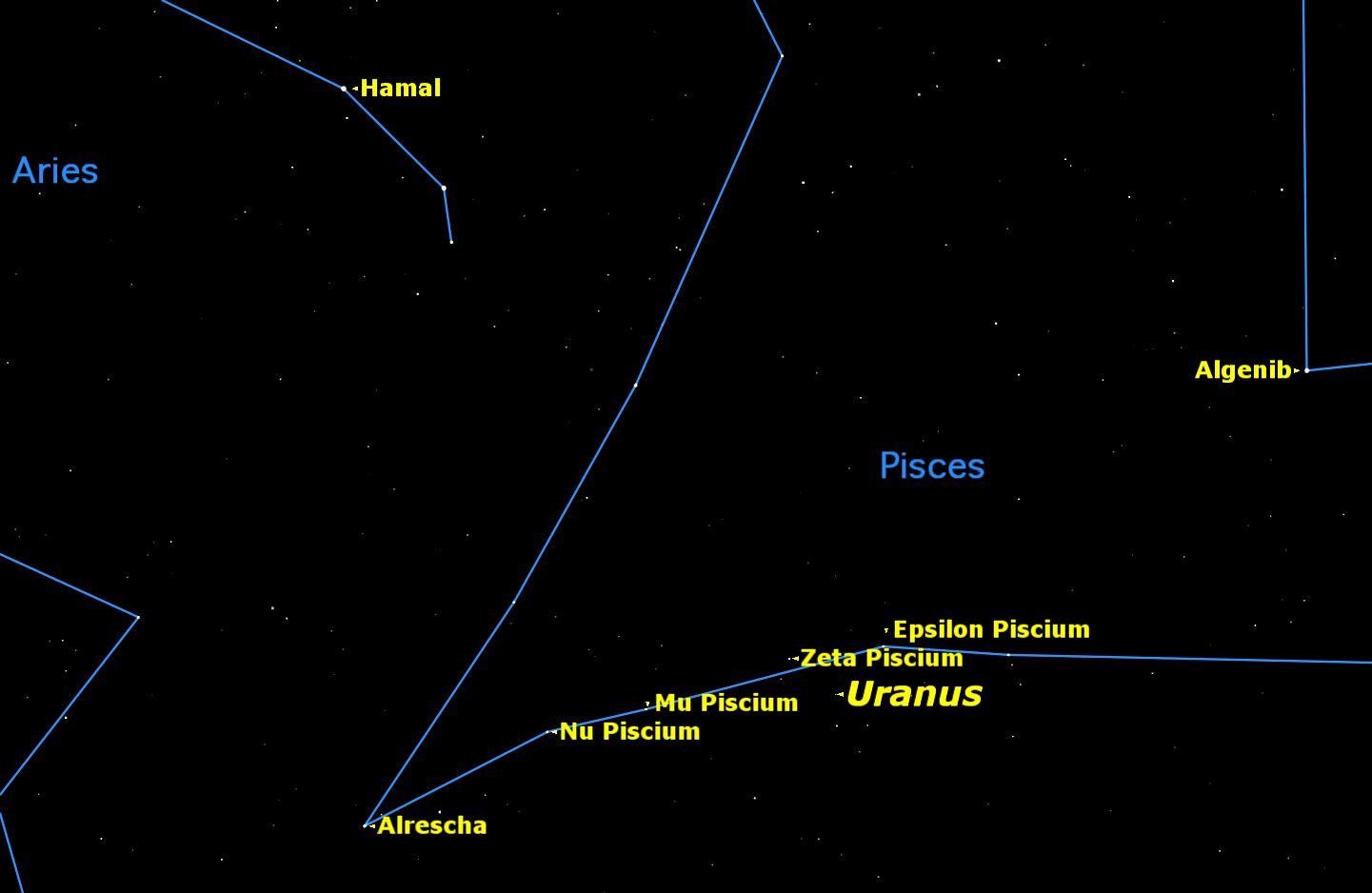

Uranus is currently visible in our early evening sky, within the dim constellation of Pisces, the Fishes. On Oct. 11 it will arrive at opposition, its furthest point from the sun, and will be visible the entire night. It shines at magnitude +5.7, which places it near the threshold of naked-eye visibility under dark, clear skies.

It is best to study the chart attached to this column first, then scan that region with binoculars. Using a magnification of 150-power with a telescope of at least 3-inch aperture, you should be able to resolve it into a tiny, pale-green featureless disk. Uranus, which on average lies 1.783 billion miles (2.870 billion km) from the sun, has a diameter of 31,763 miles (51,118 km) and, according to flyby magnetic data from Voyager 2 in 1986, has a rotation period of 17.2 hours and takes 84 years to make one trip around the sun. At last count, Uranus has 27 moons, all in orbits lying in the planet's equator. There is also a complex of nine narrow, nearly opaque rings, which were discovered in 1978.

Uranus, Neptune, Jupiter and Saturn are all rather similar in the sense that their interiors consist mainly of methane, water and ammonia, encased in an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

But the most bizarre thing about Uranus is the tilt of its axis with respect to the plane of its orbit. The other seven planets are tilted somewhere between 3 and 29 degrees.

Uranus is tilted at 97.8 degrees.

So from our Earthly perspective, seasons on Uranus are extreme: when the sun rises at its north pole, it stays up for 42 Earth years; then it sets and the north pole is in darkness for 42 Earth years.

Neptune in the night sky

In contrast to Uranus, distant Neptune is much too faint to be perceived with the unaided eye. Its average distance from the sun is 2.795 billion miles (4.497 billion km); the eighth and (since the demotion of Pluto to dwarf planet status in 2006) farthest planet in the solar system.

It is slightly smaller than Uranus, with a diameter of 30,250 miles (48,682 km). Currently at magnitude +7.9, it's more than six times dimmer than Uranus. Nonetheless, if you have access to a dark, clear sky and carefully examine our map, you should have no trouble in finding it with good binoculars. The planet currently resides in the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Carrier. It arrived at its opposition to the sun on Aug. 31 and is now highest in the south in the middle of the evening. [Photos of Neptune, The Mysterious Blue Planet]

With a telescope, trying to resolve Neptune into a disk will be more difficult than it is with Uranus. You're going to need at least a 4-inch telescope with a magnification of no less than 200-power, just to turn Neptune into a tiny blue dot of light.

Neptune's atmosphere has an active and visible weather pattern, driven by the strongest sustained winds of any planet in the solar system, with recorded wind speeds as high as 1,300 miles (2,100 km) per hour.Its period of revolution around the sun equals 164 years.

In 1989, Voyager 2 revealed the existence of at least three rings around Neptune, composed of very fine particles. Neptune has 14 moons, one of which — Triton — has a tenuous atmosphere of nitrogen and at nearly 1,700 miles (2,700 km) in diameter, is larger than Pluto. Because it is moving in a retrograde (backward) orbit, there are suggestions that Neptune may actually have captured it in the distant past. Those who have access to a telescope of 12 inches or more might even be able to get a glimpse of Triton, very close to Neptune itself.

Neptune's discovery came about from long-term observations of Uranus. It seemed to astronomers that some unknown body was somehow perturbing Uranus' orbit. Then, as so often happens in science, two men attacked the problem at the same time without knowing of each other's intentions.

In England, young John Couch Adams, just out of college, proved by mathematics that there must be an unseen planet beyond Uranus and indicated where in the sky it might be found. Meanwhile, in France, Urbain J.J. Leverrier came up with a similar solution. Both believed that the unseen body was then in the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Carrier, where Neptune resides today.

Adams and Leverrier appealed to other astronomers for help in tracking down the planet. In England, James Challis, the director of the Cambridge Observatory, searched for the planet during the summer of 1846 following Adams' directions. Amazingly, Challis actually saw Neptune twice — but failed to recognize it because he was using an out-of-date star map!

Meanwhile, on Sept. 23 of that year, a letter arrived at the Berlin Observatory from Leverrier requesting that they search in the place he suggested. Johann Galle and Heinrich d'Arrest did exactly as instructed and found the new planet in less than an hour.

Sometimes I wonder why Adams and Leverrier did not actually look for Neptune on their own. It appears that they both preferred spending much of their free time working out complicated mathematical problems as opposed to actually looking through the eyepiece of a telescope.

Desk men to the end!

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing image of the night sky that you would like to share with Space.com and its news partners for a story or photo gallery, send photos and comments in to: spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.