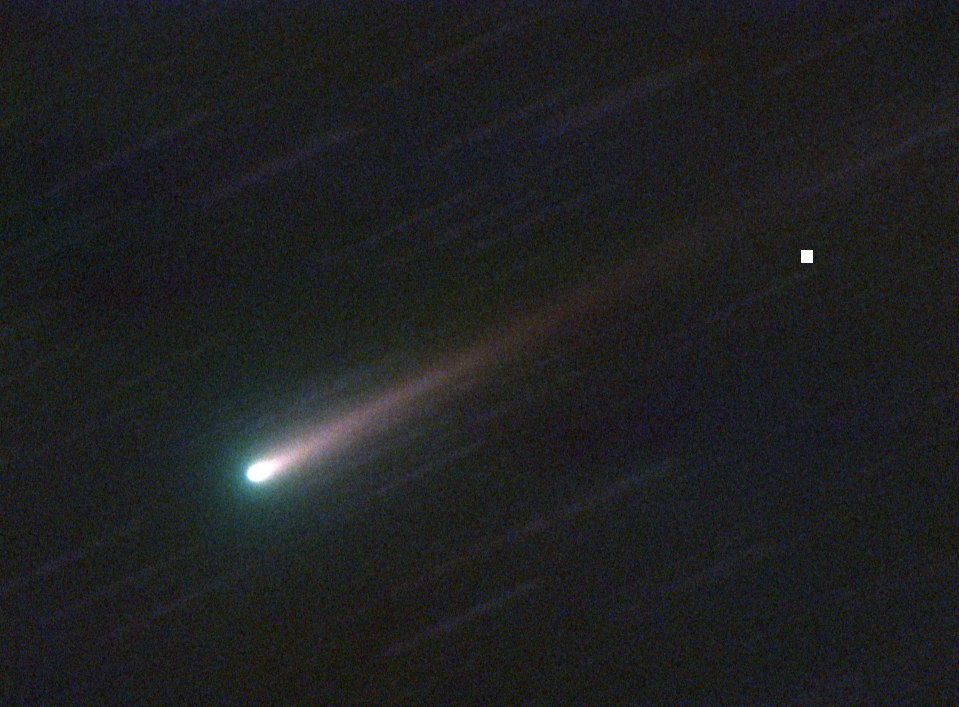

Comet's Close Encounter with Mars Dumped Tons of Dust on Red Planet

Comet Siding Spring's close shave by Mars last year provided a rare glimpse into how Oort Cloud comets behave, according to new research.

The comet flew by Mars at a range of just 83,900 miles (135,000 kilometers) — close enough for the outer ridges of its tenuous atmosphere to pummel the planet with gas and dust.

In just a short flyby, the comet dumped about 2,200 to 4,410 lbs. (1,000 to 2,000 kg) of dust made of magnesium, silicon, calcium and potassium — all of which are rock-forming elements — into the upper atmosphere, the new study found. [Comet Siding Spring's Mars Flyby in Photos]

Comet Siding Spring also left behind a substantial quantity of carbon dioxide, nitrogen and water that couldn't be detected because Mars' atmosphere is also made up of those elements. However, the long-term effect was minimal, said lead author Carey Lisse, a senior astrophysicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Research Laboratory.

"It was pretty transitory," Lisse told Space.com. "The Martian skies were polluted by the dust, but it looks like it lasted for a Martian day or two, and then it relaxed afterwards."

Small nucleus

Siding Spring's journey from the Oort Cloud — a collection of comets beyond the orbit of Neptune that stretches for hundreds of astronomical units — meant it was pristine when it showed up beside Mars.

Current rocket technology is not capable of going after these faraway comets, so having Siding Spring come so close to Mars allowed for a rare close-up view of the comet's nucleus from NASA's Mars fleet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Pictures from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter revealed a nucleus of just 0.4 miles (0.7 km), smaller than the typical Kuiper Belt (near Jupiter) comet that repeatedly enters our solar system. In fact, given that the solar system has been around for 4.5 billion years, a Kuiper Belt comet of that size probably would have evaporated by now due to the sun's heat and particle pressure, Lisse said.

Another Mars orbiter, NASA's MAVEN spacecraft (the name's short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission), arrived at the planet in October 2014 and was able to monitor Comet Siding Spring's effects on Mars' atmosphere. Meanwhile, the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers took pictures of the comet from the Martian surface— the first time these types of pictures had been taken in another world.

Solar system history

There is still considerable debate as to whether water and other life-bearing elements came to Earth via comets. While a study of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (studied by the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft) showed that the ratio of deuterium (a heavy form of hydrogen) to hydrogen was different from that on Earth, other studies show that Kuiper Belt comets may be more similar, Lisse said. "We go back and forth," he added.

But Siding Spring's close approach could have been representative of what happened commonly in the early solar system — repeated close shaves and hits by comets and asteroids that, over long periods, delivered elements to Earth and the other planets, he said.

Lisse praised the ability of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to assess the dust risk of the comet and to tailor spacecraft observations accordingly — for instance, by placing Mars between the spacecraft and the comet during its closest approach.

Amateur astronomers also played a key role in observations. In fact, it was a group of amateur skywatchers in South Africa that first alerted the astronomical community that Siding Spring had passed by Mars intact, Lisse said.

Lisse looks forward to cooperation between professionals and amateurs in 2017 and 2018, when comet 46P/Wirtanen (the first target of Rosetta) will come fairly close to Earth and will shine at an estimated magnitude 3 on the brightness scale used by astronomers. For comparison, the dimmest object in the night sky visible to the unaided eye is a magnitude 6 on the scale. Several other fairly bright comets will also come, such as 2P/Encke and 41P TGK.

The results of the study were published today (Oct. 15) in the journal Science.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.