Space.com senior writer Mike Wall is in Chile this week chronicling the groundbreaking ceremony for the Giant Magellan Telescope this week. Read his dispatches about his trip to Chile's high Atacama Desert:

Nov. 12: Chile's astronomy riches

At the groundbreaking ceremony for the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) on Wednesday (Nov. 11), Michael Hammer, the United States' ambassador to Chile, called the South American nation an "astronomical superpower."

It's easy to see where Hammer is coming from. The Chilean highlands' famously dark, dry and clear skies have lured astronomers from around the world for decades. The nation hosts such scientifically important telescopes as the Paranal Observatory, La Silla Observatory, the Magellan Telescopes, the Gemini South Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), to name just a few.

And more are coming, including the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), GMT and the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT). GMT will be the world's largest optical scope when it begins science operations in 2021 or 2022, but it will lose that title to E-ELT (and the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawaii) a few years later.

Chile obviously values these observatories and the international partnerships behind them; President Michelle Bachelet attended GMT's groundbreaking ceremony, as well as LSST's, which occurred this past April.

But what does the nation value, exactly? What does Chile get out of all this astronomy infrastructure, which, after all, tends to be run by foreigners? I asked several astronomers and GMT team members these questions over the past few days, and several answers came up repeatedly: Money (though probably not enough to make much of a difference in Chile's broader economy), jobs and prestige.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But perhaps the most important thing, multiple people said, is technical expertise, training and inspiration. Indeed, Hammer and Bachelet both stressed the importance of getting more kids interested in science and engineering, and creating an educated, highly skilled workforce. It's likely that Bachelet and other Chilean officials hope that partnering with international researchers on projects such as GMT, E-ELT and LSST generates more Chilean astronomers — and scientists and engineers of all stripes — down the road.

Nov. 11: Dark southern skies

It's almost midnight. I'm in a bus heading down the mountain from Las Campanas Observatory to the coastal city of La Serena, about 2.5 hours' drive away, and my head is swimming with everything I saw tonight.

The groundbreaking ceremony for the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) this evening was fascinating, entertaining and faintly surreal, featuring as it did the president of Chile whacking a rock with a golden hammer. (This was not an exercise in absurdist theater; Las Campanas — which means "the bells" in Spanish — was named after the odd ringing rocks in the area.)

Chilean schoolkids then performed a 20-minute interpretive dance routine for the 200 or so attendees, who proceeded to tuck into a buffet dinner fit for a head of state. There were five different kinds of salad, nearly as many types of roasted meats, quiche Lorraine and ceviche, among other things. I'm not sure what the dessert was, because I skipped that course to watch the sun set over the Andean foothills to the west.

I did not regret this decision. The golden light faded to gray, and then the fog hugging the lowlands near La Serena began glowing deep red, like a giant log that has been reduced to embers after burning all night. The wind, which had been howling in great rushing gusts all evening, shaking the big white tent during the groundbreaking ceremony, felt even colder with the sun now gone from the sky.

But the coming darkness was very much welcome, for I was about to get a taste of what brings astronomers to the Chilean Andes — the gorgeously clear night sky.

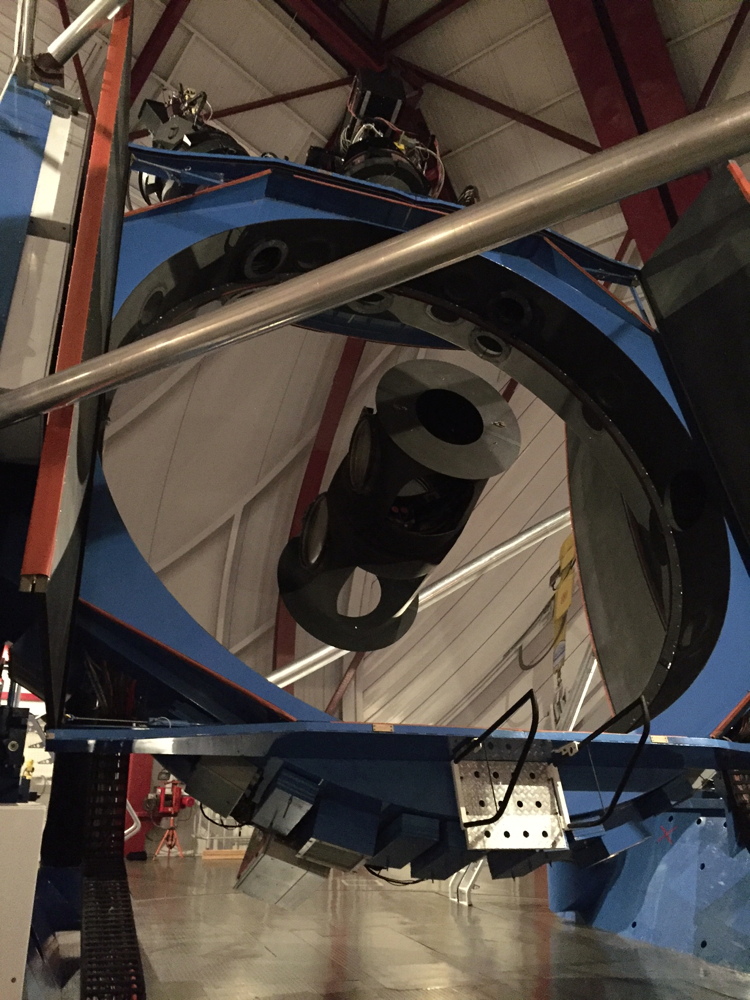

After sunset, the Giant Magellan Telescope Organization took everyone over to the Magellan Telescopes, a pair of 21-foot-wide (6.5 meters) scopes on an adjacent hillside. (For comparison, GMT's light-collecting surface will be about 82 feet, or 25 m, wide.)

While we waited to tour the facility, we craned our necks up to take in the amazing vistas overhead (though this was done in spurts, since the frigid wind chased people inside the support buildings regularly). Several Las Campanas astronomers had set up small telescopes to show folks globular clusters and nebulae, which were very nice to look at. But mostly I just stared up, taking in the cosmic immensity with my unaided eyes. I saw the Large Magellanic Cloud and the Small Magellanic Cloud, the band of the Milky Way, the zodiacal light (which is caused by sunlight hitting deep-space dust), two meteors and stars beyond counting. It was incredible.

An hour or so ago our group got called in to view one of the Magellan scopes. We strolled around inside the dome and marveled at the giant, shiny, perfectly smooth mirror pointed toward the heavens. The plan had called for us to look through the telescope's eyepiece, which would have been fantastic, but that didn't work out; the wind was gusting at more than 40 mph (64 km/h), so operators had to close the dome.

Our bus just left the dirt observatory road, turning onto the main highway back to La Serena. The dark Andean skies, studded with jewels both large and small, bright and subtle, are now fading into memory, as everything must. Maybe they'll work their way into my dreams tonight.

Nov. 11: At the telescope site

I'm standing inside a giant white tent near where the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) will be built, at the Las Campanas Observatory in the Chilean Andes.

I'm one of several hundred people who are nibbling hors d'oeuvres, listening to the wind howl and waiting for Chilean President Michelle Bachelet to get here.

Various dignitaries will speak here at the GMT's groundbreaking ceremony, but President Bachelet is the biggest name. Her participation had been expected and hoped for, but heads of states' schedules are busy and ever-changing, so a buzz went through the crowd when somebody grabbed the microphone and announced that President Bachelet is now on the road up to Las Campanas. (She apparently took a helicopter from Santiago to a little-used landing pad near the observatory.)

Now we are taking our seats, waiting for what comes next. The wind continues to howl.

Nov. 10: Flying over the Andes

The first thing I saw this morning was the sun climbing high over the Chilean Andes.

It wasn't a particularly restful night; I was on a red-eye from Houston to Santiago, Chile, and I'd managed to catch a few hours of sleep after watching "Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation" on my seatback entertainment center.

I had a window seat, and the drawn white shade blazed yellow-orange in the morning light. I lifted it and, bleary-eyed, beheld a sea of fog lapping at the foothills of the Andes, whose highest peaks were wreathed in clouds. Based on the flight map, I think the biggest mountain in view was Aconcagua, which, at 22,841 feet (6,962 meters), is the tallest peak outside Asia.

We touched down in Santiago about 45 minutes later. I'll be here until Tuesday morning (Nov. 11), when I catch a 1-hour flight to the city of La Serena. From there, it's a 2.5-hour bus ride up to Las Campanas Observatory, where the groundbreaking ceremony for the Giant Magellan Telescope will take place tomorrow evening.

Nov. 10: Springtime in Santiago

It's spring in the Southern Hemisphere, and the arid hillsides in and around Santiago are awash in color — mostly the yellow-orange of poppies, but pale yellows and blazing reds liven the landscape as well.

I saw this floral display first-hand today during a hike through Santiago's Parque Metropolitano, a large green (and brown) space in the northeastern part of this city of 5.1 million people. Some trails in the hilly park offer great views of the city, which is hemmed in by snowcapped mountains — a huge, sprawling beast trapped in a cage of rock.

Other signs of spring abounded in Parque Metropolitano: Butterflies and bees flitted from flower to flower, and lizards scurried underfoot, seeking cover beneath trailside rock and brush. But winter is a permanent presence here, at least visually, looming forever overhead in the towering Andean peaks.

The giant, gleaming tower in the photo above, incidentally, is the 64-story-high Gran Torre Santiago, the tallest building in Latin America.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.