These Ancient Stars May Be the Oldest Ever Seen in the Milky Way

Astronomers have found what may be the oldest stars in the Milky Way. The stars, discovered in the galaxy's bulge, reveal that extraordinarily powerful explosions known as hypernovas might have dominated the Milky Way during its youth, researchers say.

The oldest stars in the universe are poor in what astronomers call "metals" — elements heavier than helium. When these stars died in giant outbursts known as supernovas, they released these metals into the cosmos, and each succeeding generation of stars is generally more metal-rich than the last.

Previous research suggested the first stars formed about 13.6 billion years ago, within 200 million years of the Big Bang, initiating what scientists call the cosmic dawn. Astronomers have not yet discovered a first star, but extremely metal-poor stars that were probably immediate successors of the first stars have been seen in the outer regions, or "halo," of the Milky Way. [Watch: The Universe's Oldest Stars May Be Close to Us]

Still, prior studies indicated that extremely metal-poor stars should mostly be found not in the halos of galaxies, but in their central regions, or "bulges." Galactic bulges are loaded with gas and dust — the building blocks from which stars are born.

Stars from the cosmic dawn

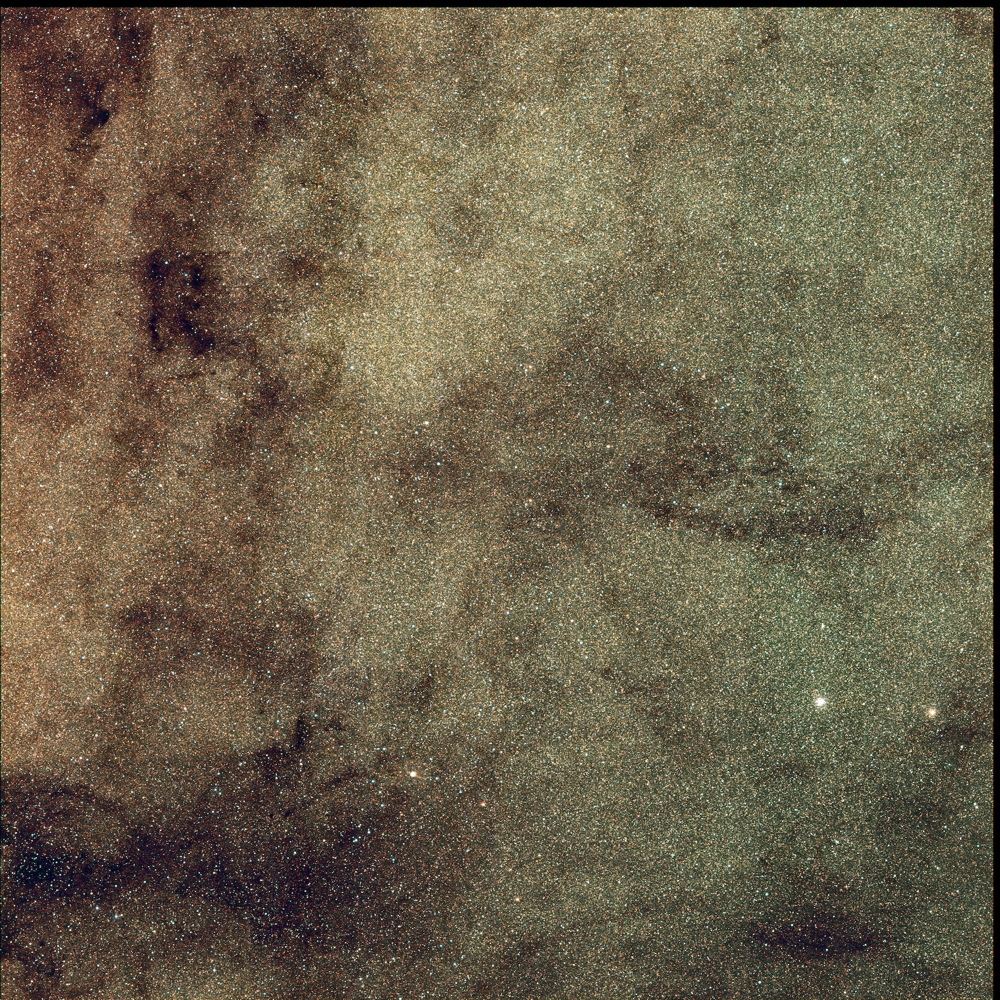

Until now, astronomers had not detected any extremely metal-poor stars in the Milky Way's bulge, in part because Earth is located in the Milky Way's halo, and the bulge is very far away, with a lot of intervening dust obscuring Earth's view of the bulge.

In addition, the vast majority of the stars in the Milky Way's bulge are metal-rich. Because the bulge is dense with gas and dust, star formation happened quickly there, and when the galaxy's early stars died, they enriched their surroundings with heavier elements within the first 1 billion to 2 billion years of the universe. This makes finding extremely metal-poor stars in the Milky Way's bulge "like searching for a needle in a haystack," said study lead author Louise Howes, an astronomer now at Lund University in Sweden, who carried out this research while at Australian National University in Canberra.

Now, Howes and her colleagues have, for the first time, identified stars from the cosmic dawn in the Milky Way's bulge.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"These are the oldest stars that have ever been found in the Milky Way," Howes told Space.com.

The researchers used the Australian National University's SkyMapper telescope to scan about 5 million stars in the Milky Way's bulge. They focused on the fingerprints of elements in the stars, which appear as distinct lines in the spectrum of their light.

A starry sleuth job

After using SkyMapper to discover more than 14,000 potential extremely metal-poor stars, the scientists used the Australian Astronomical Observatory's Anglo-Australian Telescope to confirm that more than 500 of these stars were extremely metal-poor, each possessing less than one-hundredth the amount of iron seen in the sun. As expected, most of the extremely metal-poor stars that astronomers now know about are found in the galaxy's bulge instead of its center.

Using the Magellan Clay telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, the astronomers closely analyzed 23 of the most metal-poor bulge stars to determine their chemical composition. Oddly, the researchers found that these bulge stars were as poor in carbon as they were in iron. In contrast, metal-poor stars in the galaxy's halo are often rich in carbon, possessing as much as the sun does.

"That's surprising — it's goes against what was predicted," Howes said.

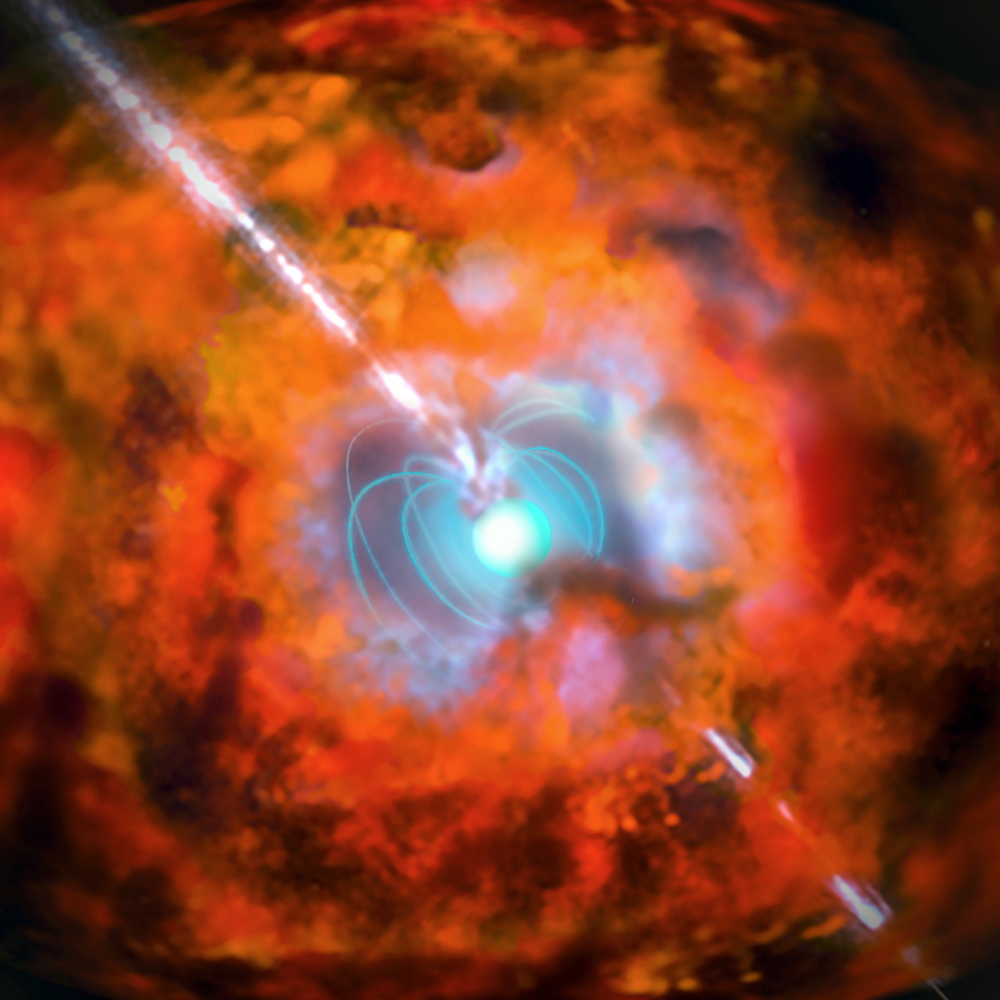

These findings suggest that the earliest stars might not have died in normal supernovas, but in titanic explosions known as hypernovas, which are 10 times more powerful than regular supernovas.

"This work really changes our ideas of what the first stars would have looked like, and how they would have developed and died, and how the galaxy would have evolved, and also sheds light on the formation of all the elements in the universe," Howes said.

This research analyzed only one-third of the part of the sky that the Milky Way's bulge covers. Future research could analyze the rest of the bulge that astronomers can see, so they can learn more about the metal-poor stars there, Howes said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Nov. 11 in the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us