In Alien Solar Systems, Twin Planets Could Share Life

Alien planets that are close neighbors to each other around the same parent star could help each other support life, creating what scientists are now calling "multihabitable systems."

In the past 25 years, astronomers have confirmed the existence of more than 1,900 exoplanets, or alien planets around other stars. Past research suggested that billions of exoplanets are potentially habitable in the Milky Way — that is, they lie in the habitable zones of their parent stars, where temperatures are right for liquid water to exist, and thus life as it is known on Earth.

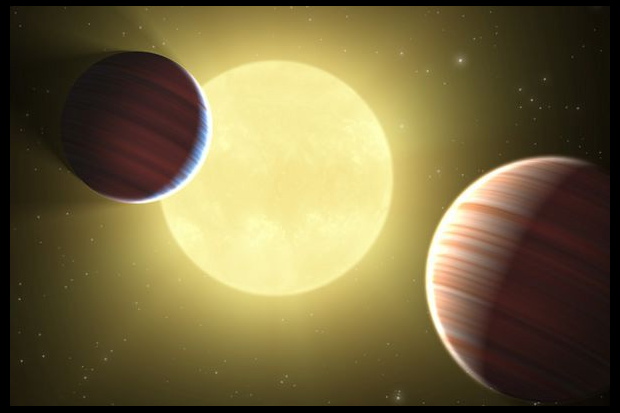

Two exoplanets that astronomers recently discovered around the star Kepler-36 are so close together they could experience a planetrise, similar to moonrise on Earth. Their parent star Kepler-36 is located about 1,200 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus (The Swan). If this system was scaled up "to the size of the Earth's orbit, then the two planets would only be one-tenth of one astronomical unit apart at their closest approach — that's only 40 times the distance to the moon," study lead author Jason Steffen at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said in a statement. [10 Alien Planets That Might Support Life]

An astronomical unit (AU) is the average distance between the sun and Earth, about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). At best, Mars and Earth are about one-half of an AU apart, or 200 times the distance between Earth and the moon.

The discovery of Kepler-36's two planets raises the possibility of multihabitable systems with two or more Earth-sized planets orbiting near each other in the habitable zones of their stars. To see what life might be like on such worlds, the scientists ran a series of computer models simulating multihabitable systems.

The researchers discovered that climates might be stable on planets in multihabitable systems. The seasons and climate on Earth depend on its obliquity, or the 23.5-degree tilt of the Earth's axis relative to its orbit around the sun — for instance, at Earth's poles, the lengths of days and nights change drastically over the course of the year, but at the equator, they stay about the same over time. A change in obliquity of only a few degrees can set off ice ages, but the scientists found that it was unlikely that gravitational interactions between planets on closely neighboring orbits would trigger large changes in the obliquities of the orbits of those worlds.

"We found that the obliquities of the planets in multihabitable systems were not really affected by their close orbits," study co-author Gongjie Li at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., said in a statement. "Only in rare instances would their climates be altered in dramatic ways. Otherwise, their behavior was similar to the planets in the solar system."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

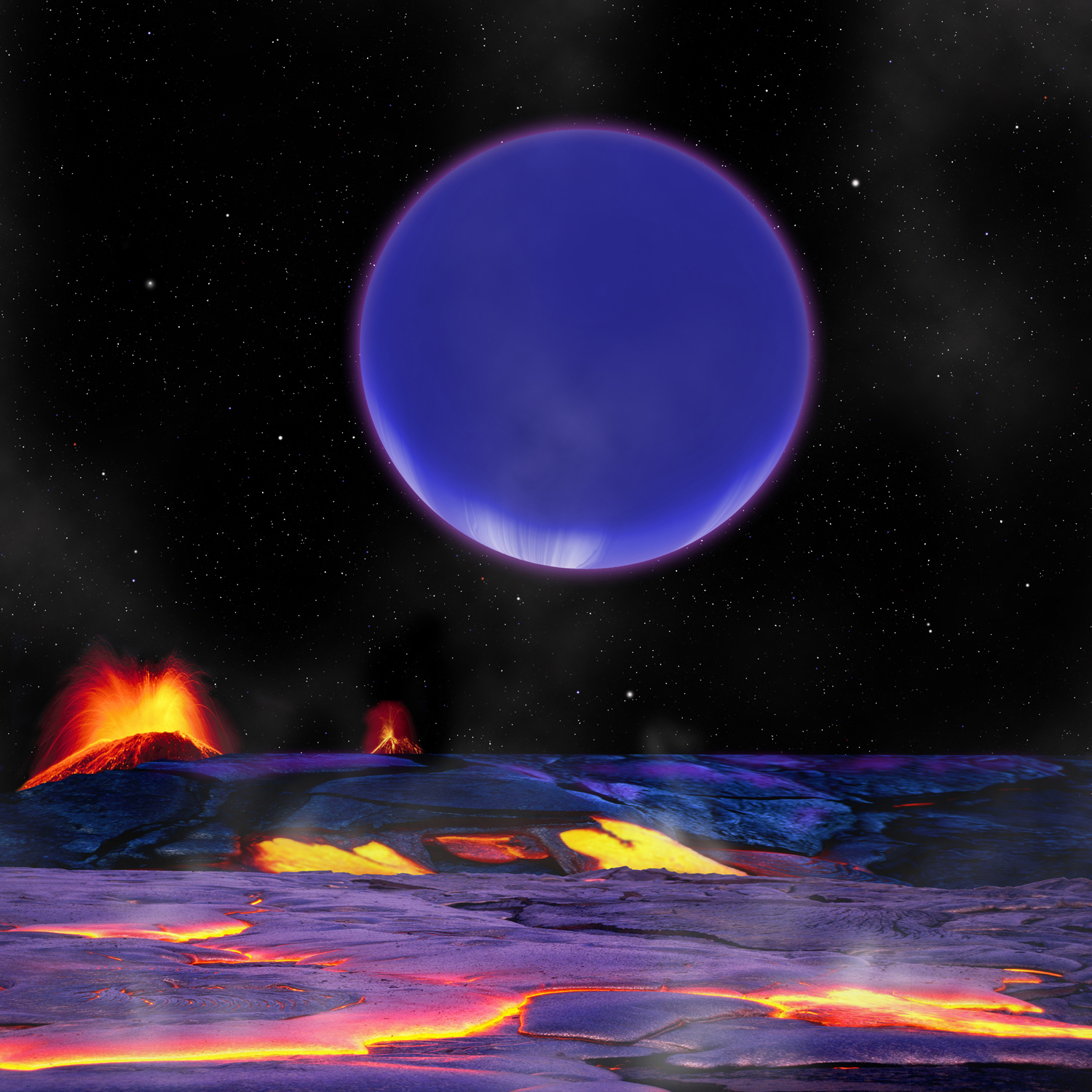

The scientists also found that each planet in this scenario could be capable of seeding its partner with life. Cosmic impacts regularly blast debris off planets that can crash on nearby planets — for example, past research discovered more than 100 meteorites of Martian origin on Earth. In principle, such meteorites could bring life-bearing material from one world to another, a process called lithopanspermia.

It remains uncertain whether lithopanspermia was possible between Mars and Earth. The great distance between the planets means it would take a lot of time for meteorites to bridge the gap between the worlds, making it less likely for any hitchhikers to survive. Powerful impacts are also needed to hurl meteorites across such a vast distance, and the energy from such collisions might easily kill any potential stowaways.

However, since planets in multihabitable systems are much closer to each other than Mars and Earth are, microbes are more likely to both survive the impacts that launch them into space and the long times they would spend traversing interplanetary space.

"The most interesting possibility that these systems enable is a biological family tree that is shared among the two planets," Steffen told Space.com. [Video: The Search for Another Earth]

The researchers even suggested that possessing a habitable companion might help life survive on distant exoplanets.

"The climate isn't likely to be any worse in multihabitable systems, and the possibility of two planets sharing the biological burden could help the system traverse the inevitable rough times," Steffen said in a statement.

The scientists concluded that multihabitable systems are among the few scenarios "where life — intelligent life in particular — could exist in two places at the same time and in the same system," Steffen said in a statement. "You can imagine that if civilizations did arise on both planets, they could communicate with each other for hundreds of years before they ever met face-to-face. It's certainly food for thought."

However, "we have not seen a real system with aliens that are communicating with each other," Steffen emphasized.

The scientists detailed their findings Tuesday (Dec. 1) at the Extreme Solar Systems III meeting in Waikoloa Beach, Hawaii. The findings have also been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original story posted on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us