Mars on Earth: Canadian Arctic Serves as Red Planet Training Ground

Would-be Mars explorers can get a taste of what Red Planet life would be like with a trip to the Canadian Arctic.

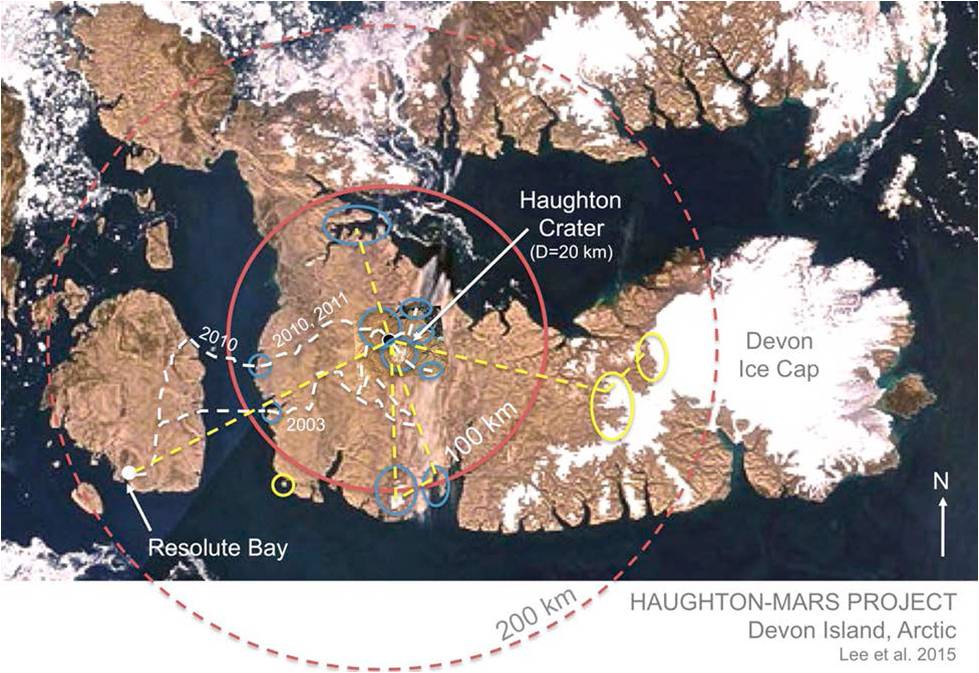

Devon Island, the largest uninhabited island on Earth, is home to the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP), an international, multidisciplinary field-research venture that aims to help lay the foundation for crewed missions to the Red Planet.

HMP started in 1997 and has been hosting NASA-supported research each year since then. The rocky, barren terrain of Devon Island offers many challenges, from remoteness and isolation to extreme temperatures and lack of infrastructure. [The 9 Coolest Mock Space Missions Ever]

But that cold-shoulder inhospitality is key to Devon Island's appeal as a Mars-analogue site.

In the right direction

"This upcoming season is our 20th consecutive field season," said HMP's mission director and principal investigator, Pascal Lee of the Mars Institute, the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute and NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

"HMP is now the longest NASA-funded research project at the surface of the Earth," Lee told Space.com.

What makes Devon Island so Mars-like?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The climate is cold — not quite as cold as Mars, but in the right direction," Lee said. "The climate is dry — not quite as dry as Mars, but it's in the right direction. And the terrain is unvegetated, not completely, but mostly. Not to mention the rocky, frozen ground and glaciers."

And there's another plus.

Impact crater

The island is scarred by Haughton Crater, roughly 12 miles (20 kilometers) in diameter and some 23 million years old.

The impact that created Haughton Crater "was so violent that it dug all the way down to a mile [1.6 km] into the rocks of Devon Island," Lee said.

As a result, the once very compact rocks of Devon are now heavily shattered and colonized by microbes.

"The upshot of this," Lee said, "is that impacts may be bad news for highly evolved creatures like dinosaurs or us … but they were a boon for microbes. Impacts brought in heat, and they created fractures and porosity in rocks to allow microbes to colonize. They were likely part of the vector for the early colonization of life on Earth."

Lee said the initial motivation to go to Devon Island was strictly scientific, because of its Mars-like setting — an impact crater in a polar desert. Around the crater are also valley networks, canyons, gullies and ancient lake beds. In terms of their detailed morphology, those features have counterparts on Mars.

"That's not to say that they were necessarily the same things that we were seeing on Mars. But there was a convergence of all these geologic features in one location," Lee said. [Photos: The Search for Life on Mars]

Cold-climate Mars

Lee said he believes that Devon Island holds important clues about early Mars. He said he's skeptical of the classical view that the Red Planet had a warm and wet climate early in its history. Instead, Lee has proposed that while the ground was warm, early Mars had a cold climate.

"The idea of a warm ground under a cold-climate Mars is still gaining acceptance," Lee said. "Impacts were dumping heat into the ground. Volcanism was also more active on a young Mars. Those two processes were injecting water vapor into a frigid atmosphere. The water vapor would then condense out onto the surface. There were transient ice covers here and there on Mars. Because the ground was warm, not the climate, these ice covers were melting from underneath, creating valley networks."

Examination of Devon Island has raised the prospect for reinterpreting the Martian landscape in terms of a cold climate, ice caps, frozen lakes and other glacial features, Lee said. Mars of old was more likely quite chilly, enveloped in a cold, frigid, thin atmosphere, much as it is today, he added.

Pilot model

With so many Mars-like attributes, Devon Island offers the perfect backdrop to plan out a crewed trip to the Red Planet, Lee said.

Devon Island is rife with canyons, valley networks, gullies, ground ice, patterned ground, debris flows, cold-desert weathering crusts and paleo-lake deposits.

HMP is a real field-exploration setting, Lee said. Valuable lessons learned at HMP are informing the planning and optimization of future human science and exploration activities on Mars, he said, including astrobiology and planetary-protection investigations.

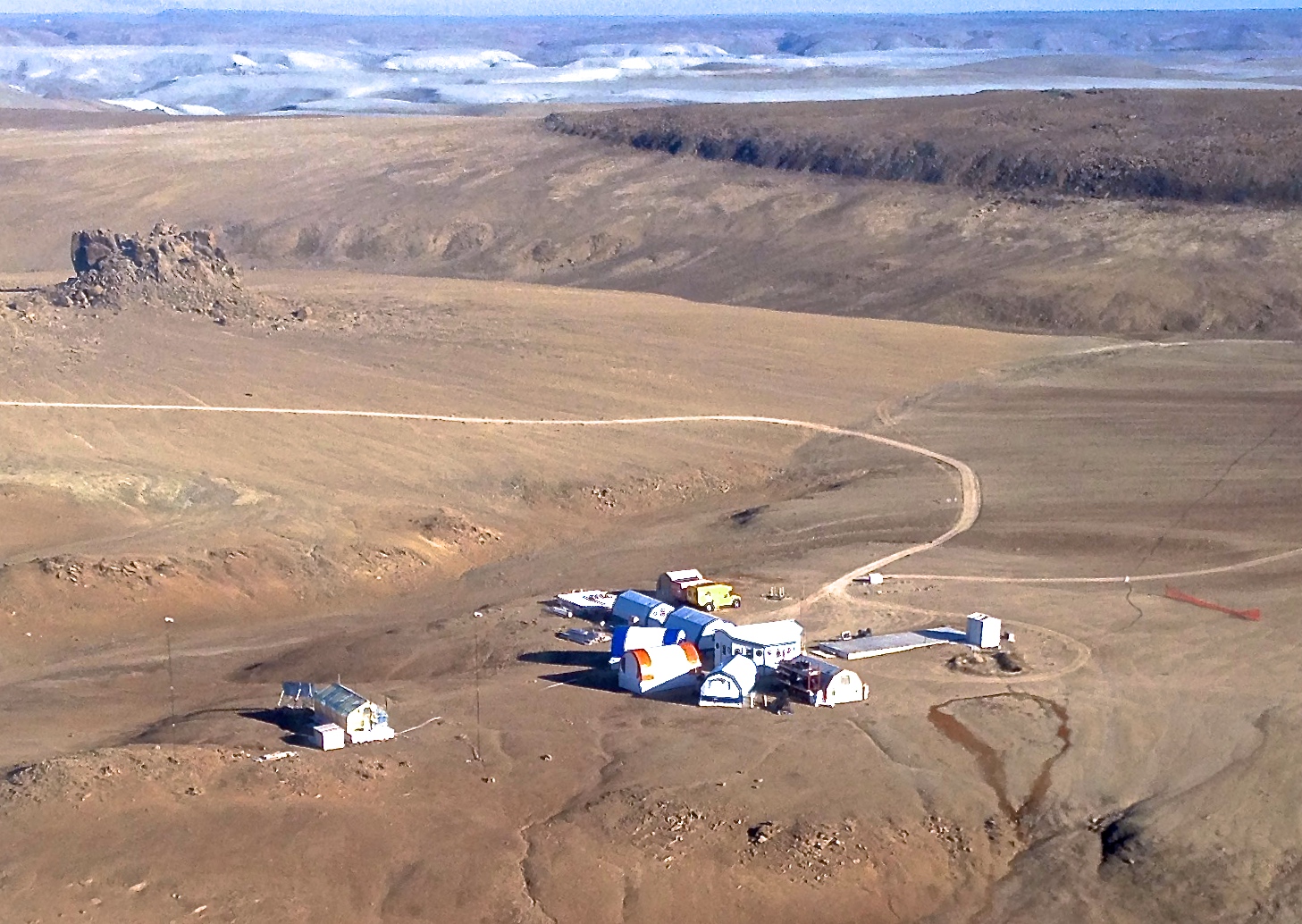

"It's a big team effort," Lee said. The HMP Research Station, the project's base camp, both satisfies scientific interests and serves as a pilot model for how a future Mars outpost might be designed and operated, he said.

"It's an infrastructure that is dedicated to advancing the exploration of Mars by robotic and human means," Lee said. "We've already had astronauts visit the place. We expect more will come as part of the actual training."

HMP expeditionary teams have tested all manner of hardware: new robotic rovers, spacesuits, drills and aerial drones. There is other gear at the site, too, including the Mars-1and OkarianHumvee rovers — the HMP's two simulated pressurized rovers for lengthy traverses into the wilderness — as well as personal all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) for short treks.

An imperative stop

"In terms of the science, I anticipate that there will be many more years of scientific work to be done on Devon Island," Lee said. "We're still making discoveries … we're still learning about the site."

Lee and a small group of other scientists from around the world are now busy plotting out the 20th HMP field campaign, which is scheduled to occur in mid-2016.

And as future human-to-Mars activities gather steam, Lee said that the experiences gleaned from Devon Island will be invaluable.

"The way I envision it, Devon Island will eventually become a training site for astronauts bound for Mars," he said. "It will become one of the imperative stops, if not the final stop, in your preparation for the Red Planet."

Lee said, with a smile, that the first words pronounced on the surface of Mars might be: "Wow! This looks just like Devon."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's 2013 book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration," published by National Geographic with a new updated paperback version released in May 2015. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.