SAN FRANCISCO — There's a good chance that NASA's highly anticipated Europa mission will do much more than just fly by the ocean-harboring Jupiter moon.

NASA has already selected the nine primary science instruments for the Europa spacecraft, whose core mission involves performing dozens of flybys to gauge the Jovian satellite's life-hosting potential. But the probe should be able to accommodate an additional 550 lbs. (250 kilograms) of payload, and NASA would rather not let that "excess" go to waste.

"There's a variety of things that we can do," Jim Green, the head of NASA's Planetary Science division, said here Tuesday (Dec. 15) during a town hall presentation at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU). "Perhaps plume probes, perhaps penetrators, or even a small lander." [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

Researchers are studying these various possibilities, and will present their findings to NASA Headquarters "in the January time frame," Green added.

There's no guarantee that any additional instruments or miniprobes will make it onboard the Europa spacecraft. But the smart money may be on one or two ultimately being selected.

"We're pretty hot on doing something," Green told Space.com after his presentation.

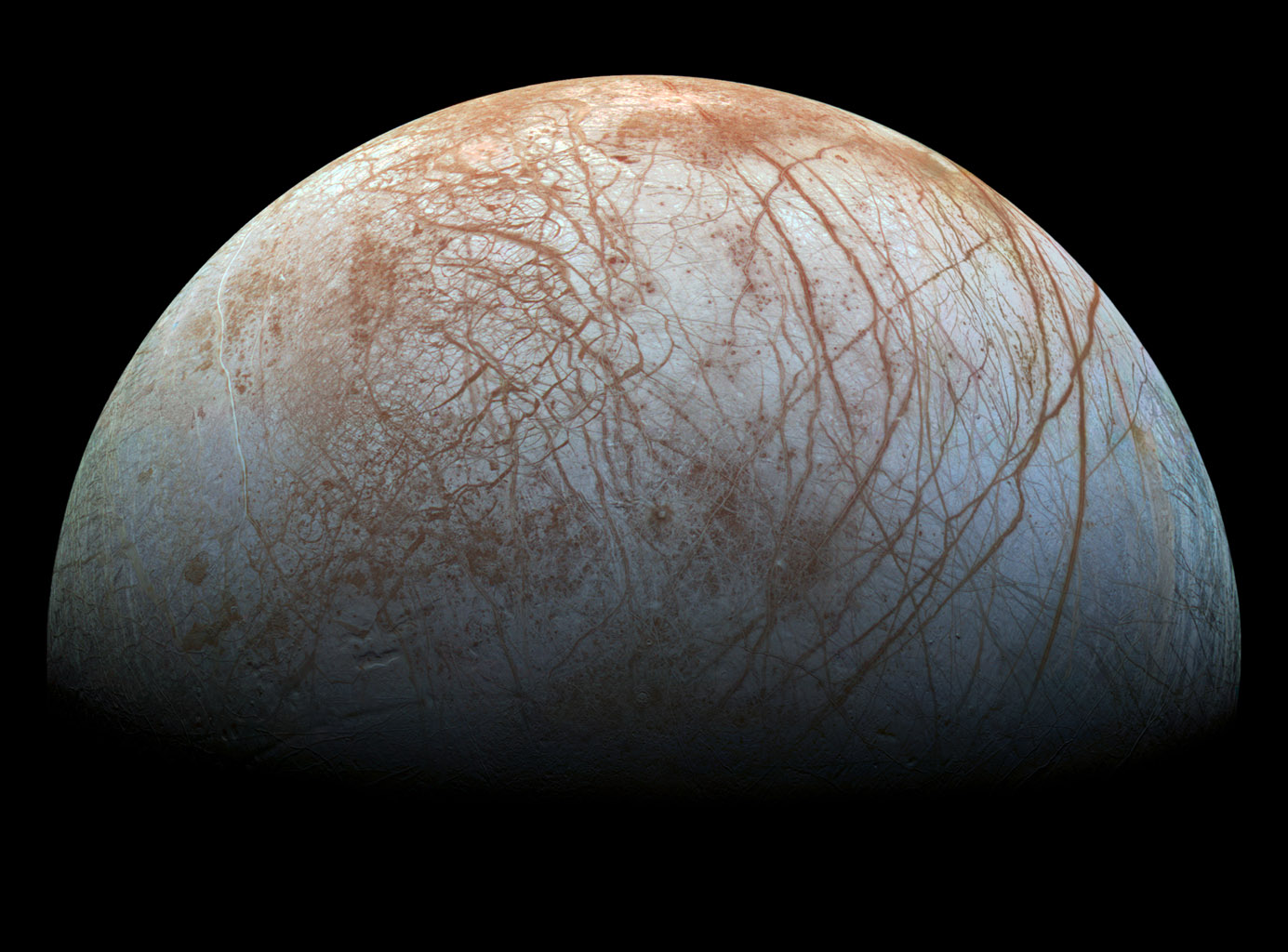

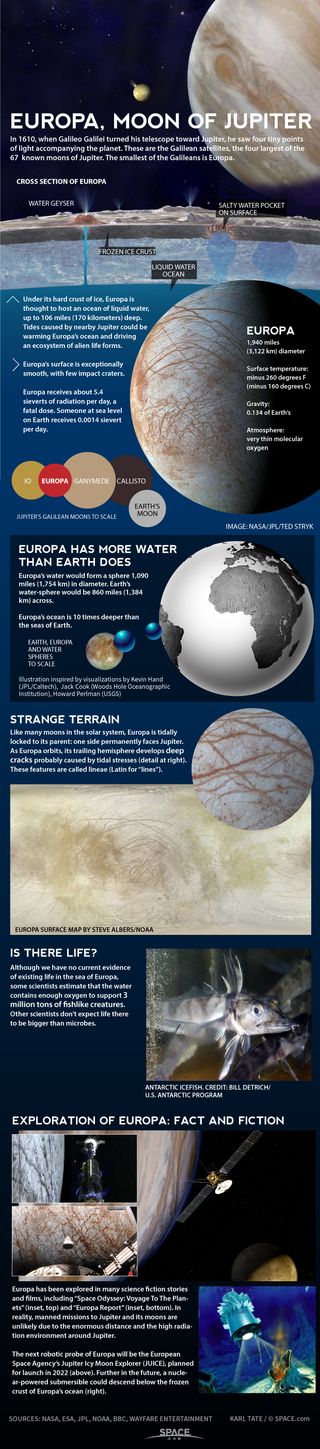

The 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) Europa is regarded as one of the solar system's best bets to host alien life. Though Europa is covered by an ice shell perhaps 50 miles (80 km) thick, the satellite also harbors a huge subsurface ocean that contains more water than all of Earth's seas combined.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This ocean is in contact with Europa's rocky mantle, making possible a range of interesting and complex chemical reactions, researchers say.

The $2 billion Europa mission, which does not have an official name yet, aims to investigate the habitability of the moon and its ocean.

The spacecraft is scheduled to launch in the early to mid-2020s and reach the Jupiter system 8 years later, if a "standard" rocket such as United Launch Alliance's Atlas V serves as the launch vehicle. (Using NASA's in-development Space Launch System megarocket would slash the travel time to 3 years or so, Green said.)

The probe would then perform 45 flybys of Europa over the next 2.5 years or so, studying the satellite with high-resolution cameras, a heat detector, ice-penetrating radar and other scientific gear.

None of the nine already-announced instruments were designed to hunt for signs of life. But it's possible that a small deployable plume probe — which would fly through putative plumes of water vapor near Europa's south pole, which were detected in December 2012 but have yet to be confirmed by follow-up observations — could carry life-detecting gear. So could a penetrator, which would slam into Europa's ice shell at high speeds, or a lander, which would touch down softly.

Europa's rough and rugged terrain — a complex jumble of big ice cliffs and crevasses — would make a soft landing extremely challenging, Green said, and surface work would be tough in the moon's high-radiation environment (though radiation levels aren't uniform across Europa, and analyses suggest that a lander could operate for extended periods in some locales, Green added).

We'll all just have to wait and see if NASA will add these challenges to its Europa to-do list.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.