Violent Impact That Created Moon Mixed Lunar and Earth Rocks

The colossal impact that created the moon may have spawned the cosmic mashup between the rocks that ultimately became Earth and its lunar neighbor, researchers say.

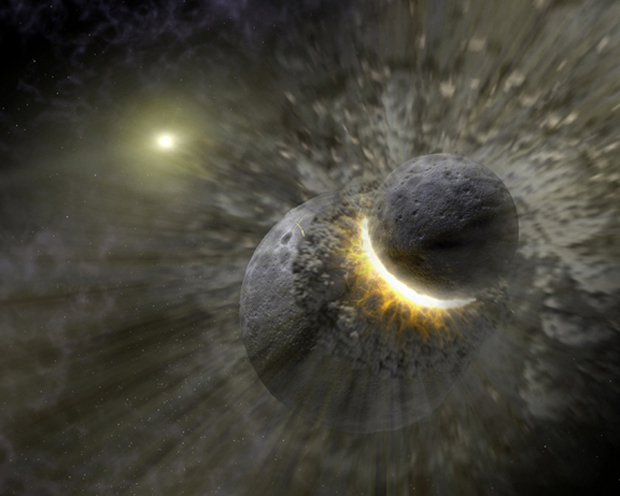

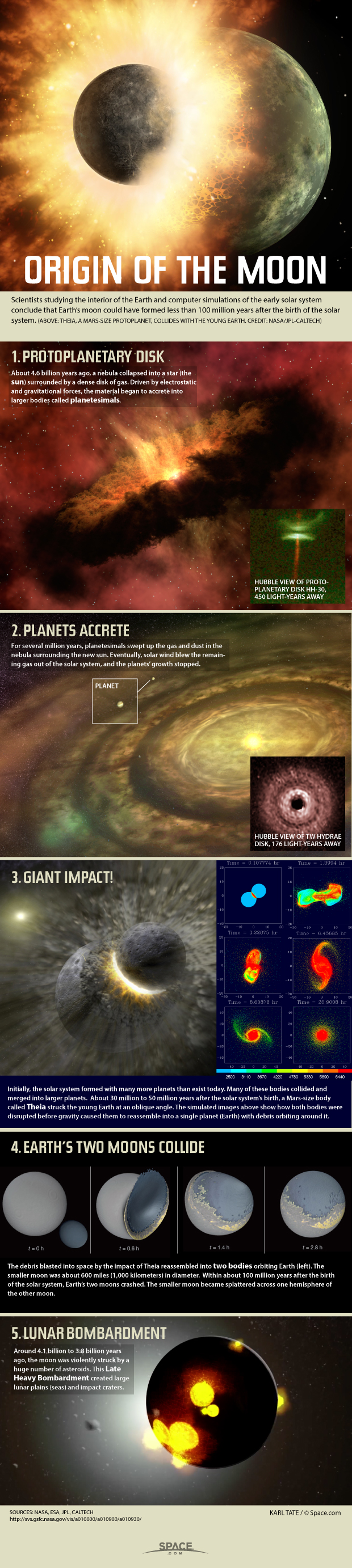

Previous research suggested that about 100 million years after the solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago, the newborn Earth was hit by a Mars-size rock named Theia, named after the mother of the moon in Greek myth. Debris from the collision later coalesced into the moon.

Much remains uncertain about the precise nature of this giant impact. For instance, scientists have long debated how much debris, including water, was exchanged between the nascent Earth and moon, and whether the collision was a glancing blow or a high-energy impact. [Watch: How the Moon Was Made, and What It Did for Life]

Now scientists find evidence that the rocks that went on to become Earth and the moon were thoroughly mixed together before they separated. This suggests that "the collision that formed the moon was a high-energy impact," said study lead author Edward Young, a cosmochemist and geochemist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Moon rocks tell the tale

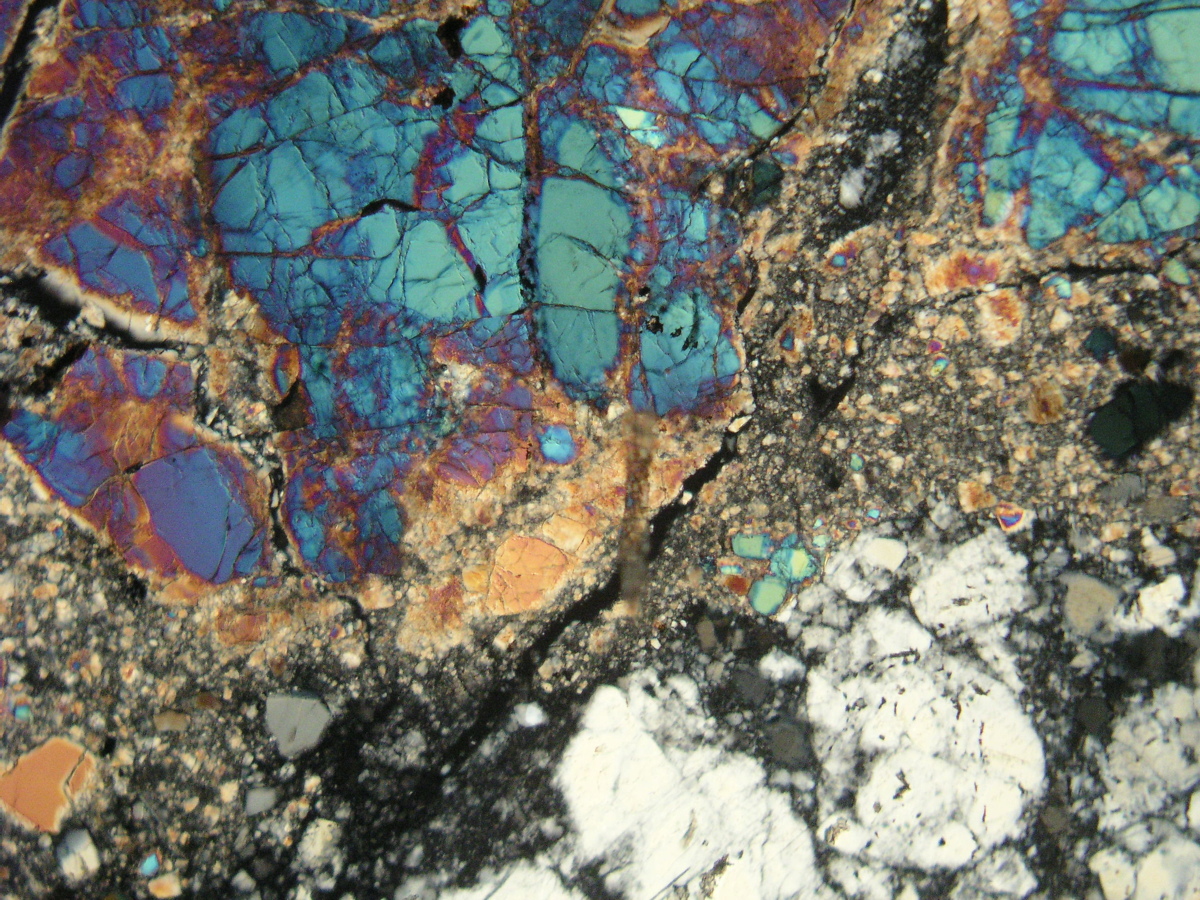

The researchers analyzed seven moon rock samples collected during the Apollo 12, 15 and 17 lunar missions. They also examined one lunar meteorite — a rock that a cosmic impact knocked off the moon, which later crashed on Earth.

The researchers focused on ratios between different isotopes of oxygen in the rocks. Isotopes of an element have differing numbers of neutrons from one another — for instance, oxygen-16 has eight neutrons in its nucleus, while oxygen-17 has nine. [Violent Birth of the Moon Explained (Infographic)]

The ratio of oxygen-17 to other oxygen isotopes typically gets smaller the bigger planets and moons get. This means that different planets and moons usually have distinct isotope signatures.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, the researchers found that Earth and the moon have indistinguishable oxygen isotope ratios, within 5 parts per million when it comes to oxygen-17.

"As we continue to improve our ability to make measurements, the moon and Earth continue to be more and more alike isotopically," Young told Space.com.

Previous research from another group in Germany found subtle differences in oxygen isotope ratios between Earth and the moon, differing by about 12 parts per million when it came to oxygen-17. This prior work suggested that less mixing occurred between Earth and the moon than now proposed.

Moon-Earth mix-up

Young and his colleagues said their analysis was more precise than previous studies because they were able to identify and overcome potentially major causes of error, such as contamination by water.

"It should be remembered that the new level of precision that we are working with is challenging, and so it is not surprising that there will be some disagreement in the beginning," Young said.

Isotope geochemist Andreas Pack at the University of Göttingen in Germany, whose group previously found oxygen-isotope ratio differences between Earth and the moon, said this new research presents "high-quality data along with a sound explanation for the surprising similarity of Earth and the moon. There is nothing for me to criticize."

These findings suggest that the newborn Earth and Theia contained substantial amounts of water bearing oxygen-17, the researchers said. This water may have come in the form of ice- or water-laden minerals, they added.

In the future, "we will be measuring many more lunar samples to get a feel for what sort of variability there might be from terrain to terrain on the moon," Young said. "For example, we see evidence for oxygen isotope differences between basalts on the moon and the highlands of the moon. These differences mimic similar variability seen here on Earth."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Jan. 29 issue of the journal Science.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally posted at Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us