When Black Holes Run Out of Gas, They Turn Off the Lights

Some of the brightest objects in the known universe may abruptly go dark at the whims of the black holes that power them, new research shows.

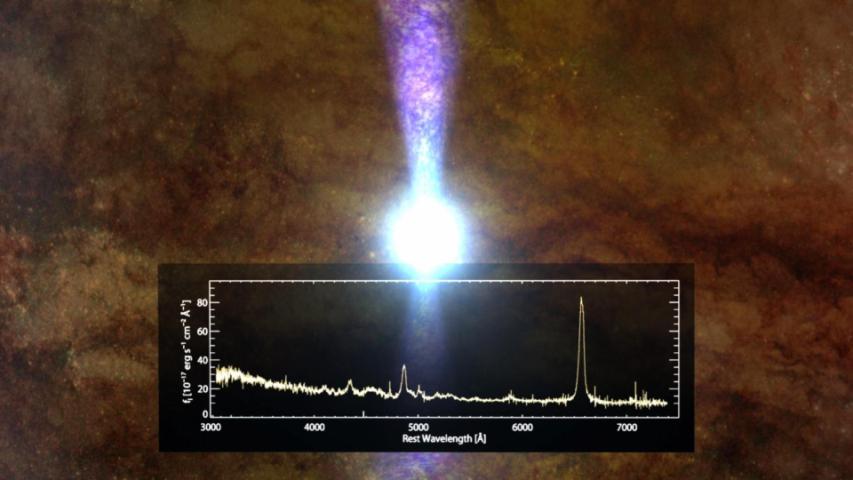

A recent study reveals a dramatic example of this newly discovered type of object, called a "changing-look quasar," which seems to have winked out in as little as a decade when its black hole no longer had gas to suck in.

"This is an intrinsic change in the gas that's falling on the supermassive black hole," Jessie Runnoe, a postdoctoral student at Pennsylvania State University and lead author of the new work, said at a news conference Jan. 8. Runnoe presented the results of the changing-look quasar at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, Florida. [The Cosmos' Most Famous Black Holes (Photos)]

"At least temporarily, the supermassive black hole has run out of fuel," Runnoe said.

"A brand-new phenomenon"

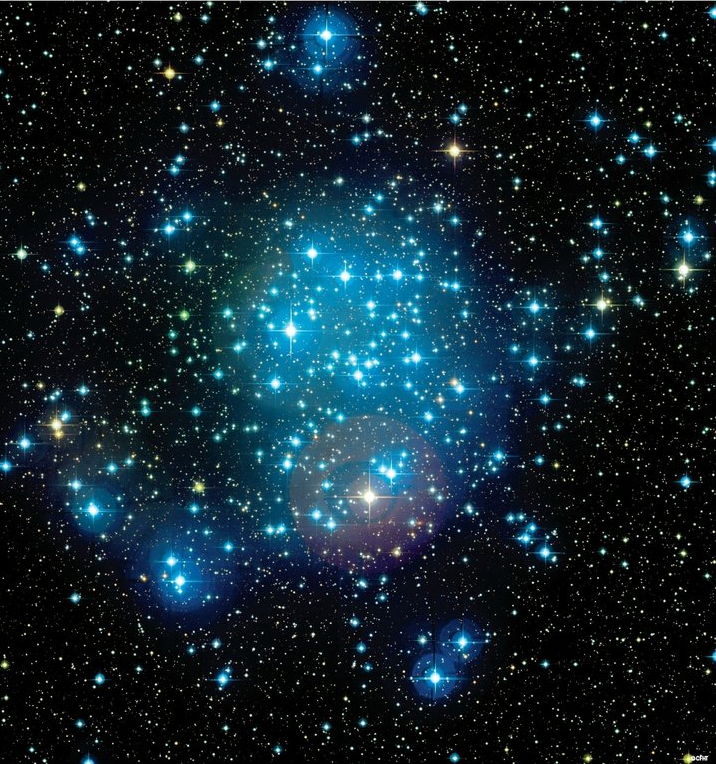

At the center of most galaxies lies a supermassive black hole weighing thousands to a billion times as much as the sun. As black holes swallow up nearby gas and dust, they can emit light and radio waves that shine brightly across the universe — a feature called a quasar.

However, if the material the black hole is sucking in runs out, the quasar's powerful light appears to shut down quickly, the new research suggests. Astronomers are used to looking at objects that change over millions or billions of years, so the researchers were surprised to spot an object that changed over a decade or less.

"This is a brand-new phenomen[on]," John Ruan, a graduate student in astronomy at the University of Washington in Seattle, said at the same conference. Ruan is co-author of the new paper, and also led an archival search for more changing-look quasars in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We've never actually seen a quasar just turn off before," he said.

In early 2015, after the discovery of the first changing-look quasar, Runnoe and her colleagues decided to visually search for the objects by eye rather than by computer in the Time Domain Spectroscopic Survey (TDSS), which incorporates data from Sloan and other sky surveys to identify objects that vary in brightness over time. And they uncovered a particularly striking example.

A strange object known as J1011+5422 lies approximately 3.4 billion light-years from Earth, and when it was first spotted by Sloan in 2003, it looked like a regular quasar. But when TDSS followed up in 2015, just 12 years later, the light from the bright quasar had faded away. Only the light from its parent galaxy shone through.

"The difference is pretty dramatic," Runnoe said. "This is the most dramatic one we've found."

Previous evidence suggested that quasars shut off over tens or hundreds of thousands of years, Ruan said.

"To observe a quasar shutting off in just a few years is very surprising," he added.

The results were detailed Nov. 18 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

"More serendipitous discoveries"

Several phenomena could be responsible for the sudden cutoff in light streaming from the quasar, and Runnoe and her colleagues sought to determine which was responsible for J1011's dramatic shutdown.

The most obvious cause would be a massive cloud of gas and dust moving between the quasar and the Earth. But after combing through more than a decade's worth of observations made by Sloan, the astronomers concluded that the quasar slowly shut down over a period of at least 7 years, finally disappearing by 2015. In contrast, it should have taken a giant molecular cloud several decades to obscure the quasar. Furthermore, the team saw no signs of the cloud's chemistry in the dimming light from the quasar — something they would have expected to see, especially as quasars are already used to study the chemistry of such clouds.

The researchers also considered that the original object was not a quasar at all but instead only an extremely bright flare caused by a star wandering too close to the black hole and being torn apart. However, such disruptions typically occur over months rather than years, making it an extremely unlikely scenario.

The most likely explanation, according to the team, is that the inner disk of material surrounding the black hole ran out, consumed by the gluttonous giant.

"If you drain the inner part of the disk, you could just shut everything down," Runnoe said.

If the rapid consumption of material turned the quasar off, it is possible that the addition of new material could activate it again at some time in the future, Ruan said.

"With continuous observation of these changing quasars, we may be able to see them turn back on," Ruan said.

Since the discovery of the first changing-state quasar in 2015, about a dozen additional changing quasars have been observed by TDSS. All of them paint a consistent picture of the material falling into the black hole being cut off and the quasar shutting down.

With so many examples found and TDSS just wrapping up the first of its five-year observing program, Ruan said this suggests that such objects may be widespread throughout the universe. He expects to spot as many as 200,000 quasars shutting off before the survey concludes in 2020.

"We expect there to be a lot more serendipitous discoveries," he said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd