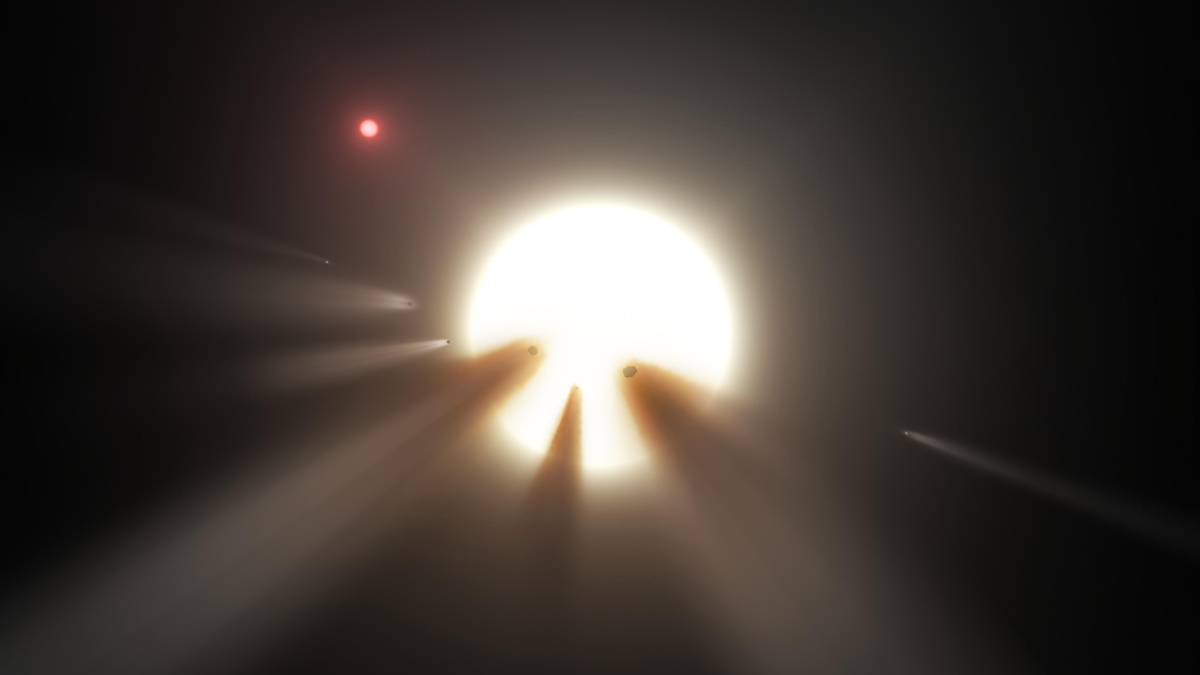

Comets May Not Explain 'Alien Megastructure' Star's Strange Flickering After All

It's looking less likely that a swarm of comets or an "alien megastructure" can explain a faraway star's strange dimming.

The star (nicknamed "Tabby's Star," after its discoverer, Tabetha Boyajian) made major headlines last October when Jason Wright, an astronomer at Pennsylvania State University, suggested that it could be surrounded by some type of alien megastructure. A more likely idea — one that's far less exciting — is that the star is orbited by a swarm of comets. But scientists can't be sure either way.

Now, Bradley Schaefer, an astronomer at Louisiana State University, has probed the star's behavior over the past century by looking at old photographic plates. Not only does the star's random dipping date back more than a century, but it also has been gradually dimming over that period — a second constraint that makes it even harder to explain. [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Alien Life]

The first signs of the star's oddity came from NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope, which continually monitored the star (as well as 100,000 others) between 2009 and 2013. Astronomers, citizen scientists and computers could then search for regular dips in a star's light — a sign that an exoplanet has passed in front of that star. The largest planets might block 1 percent of a star's light, but Tabby's star dropped by as much as 20 percent in brightness. That, in and of itself, would be weird. But the periodic dimmings didn't occur at regular time intervals, either — they were sporadic. The signature couldn't be caused by a planet, scientists said.

In September, a team led by Boyajian, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University, tried to make sense of the unusual signal. First, the researchers looked into any angles that might mean there was something wrong with the data itself. They even checked in with Kepler mission scientists. But everything came out clean. "The data that we were observing with Kepler is, in fact, astrophysical," Boyajian told Space.com.

Still, nothing about the observations indicated what might be causing the extreme interference. After considering many possible scenarios, Boyajian determined that dust from a large cloud of comets was the best explanation. But she admits that "it's a bit of a stretch to have comets that are large enough to block that much of the light from the star." With her paper published, she hoped that other astronomers would jump in with alternative solutions.

And they did. A month later, the star exploded into the public's eye when Wright announced that an advanced extraterrestrial civilization could be responsible for the signal, assuming this civilization built a megastructure, like solar panels, around the star. And Boyajian thinks the theory is definitely worth a follow-up.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have to look at every angle that we can — and that's one angle, as wild and crazy as it seems," she said. Slate blogger and astronomer Phil Plait, too, admitsthat "while it's incredibly unlikely, it does kinda fit what we're seeing."

A follow-up looking for alien signals, however, turned up empty-handed.

So Schaefer turned to old photographic plates from the Harvard College Observatory. Lucky for him, the star has been photographed more than 1,200 times as part of a repeated all-sky survey between the years 1890 and 1989. That many data points revealed that Tabby's star is acting strangely in more than one way: It's flickering on short timescales, as the Kepler and Harvard data show, and it's dimming over the course of a century, as the Harvard data show.

"Occam's razor [the simplest explanation is likely the best one] needs to be considered in a scenario like this," Boyajian said. A single phenomenon must be causing both behaviors, she added. But what is it?

Well, the results don't look good for a family of comets. It would take a vast number of comets to pass in front of the star for a century, astronomers say.

"It would be more mass than what we have in the whole Kuiper Belt" [the band of icy bodies in the vast region beyond Neptune], said Massimo Marengo, an associate professor of astronomy at Iowa State University who co-authored a paper supporting the comets theory in December.

"You can get out of that if you assume it's the same family of comets passing in front of the star over and over," Marengo told Space.com. But with the century-long dimming trend, too, that family of comets has to get bigger every time it passes the star. "It's a difficult thing to do," he said.

The results also change the requirements for the alien megastructure hypothesis. Plait pointed out that the general fading is actually what you'd expect to see if aliens were building a massive sphere around their star. But before you get your hopes up, consider this: Plait calculated that aliens would need to build a minimum of 750 billion square kilometers (290 billion square miles) of solar panels to account for the 20 percent drop in their star's brightness. "That's 1,500 times the area of the entire Earth," Plait wrote. "Yikes."

So astronomers now have to hope that future observations might shed light on this stellar oddity. "Nature can help us by creating another one of these events," Marengo said. "But sometimes, we don't get lucky."

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.