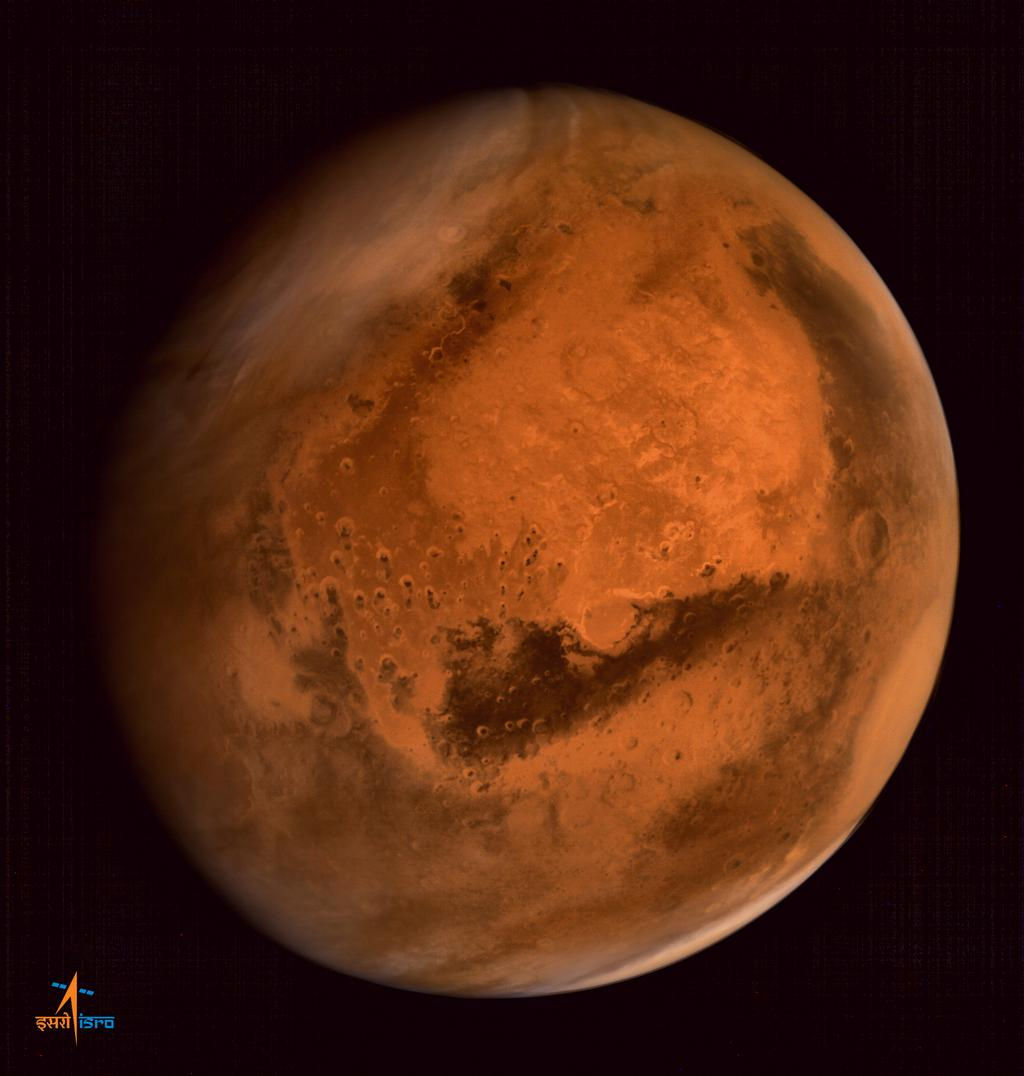

Send Humans to Mars Orbit, Not the Surface (Op-Ed)

Neil MacDonald is the editor of Federal Technology Watch and Joshua Chamot is the editor of Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights section. The authors contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices.

Establishing a permanent human presence at Mars is a daunting challenge for any nation. Yet global partners expect the United States to lead the effort, despite the policy gauntlet of new presidents every four to eight years, shifts in Congress every two years and an uncertain, evolving aerospace industry.

Under such conditions, securing a mandate for the multiyear, billion-dollar budgets to construct massive spacecraft and crew support for the first human visitors to Mars seems, at best, unlikely. [5 Manned Mission to Mars Ideas]

But what if Mars exploration were unshackled from the freeze-thaw cycles of American politics? What if instead of one massive mission to the Red Planet decades hence, public and private space industries launched dozens of smaller, more efficient coordinated missions — starting now?

We have the technology

A crewed mission to the Martian surface will likely be mired in budget talks for several political generations to come, but there is an alternative that could launch within years, not decades. If the goal shifts from establishing a colony on the Martian surface to the development of a permanent space station at Mars, crewed spaceflight can evolve from low-Earth orbit to low-Martian orbit in line with breakthroughs in transport.

This approach would combine the best successes from nearly two decades of building, operating and living safely aboard the International Space Station (ISS) with improved safety, recent developments in cargo-delivery vehicles and the critical breakthrough in orbital mechanics dictated by ballistic capture.

And it would mean the Mars mission need not rely on the budget cycle of any single nation. Instead, the existing international partners, and new members to the club, could simultaneously draw down ISS while sending a crew toward a space presence in orbit around the Red Planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Getting off planet, piece by piece

Key to starting now is sending components — including pre-assembled habitation modules modeled on the pieces that make up ISS — into orbit around Mars as part of a continuous cycle of deliveries that can launch at any time, when budgets and assembly dictate.

Such flexibility is made possible by a recent discovery in orbital mechanics. In 2014, mathematician Edward Belbruno of Princeton University in New Jersey and Francesco Topputo of Politecnico di Milano in Italy proposed a unique mechanism, called ballistic capture, to send spacecraft to Mars. By first sending a craft to one of several locations along a planet's orbit around the sun, not directly to the planet itself, the vehicle "catches up" with the planet over time.

If such a craft is heading toward a space station, or the location where a station is to be constructed, entering Martian orbit becomes the (far simpler) goal, instead of landing — which is reserved for smaller trips from station to surface. As long as missions are coordinated, then simultaneous construction projects are theoretically possible, allowing for nations or companies to send components as completed.

With launch timing nearly irrelevant, structures and supplies can be sent on a regular schedule, in manageable sizes, using mostly standard modular units. These would be space equivalents of the ubiquitous shipping containers that dominate most cargo movement on Earth.

This orbital pre-colonization allows a Mars mission with an international crew to overcome three critical obstacles:

- Crew safety concerns, as protection would be provided by mechanisms similar to those safeguarding crews on ISS, enhanced with current knowledge from long-term astronaut missions

- Time delay for communications to the Martian surface

- Budgetary delays, as competing ventures, or nations, can independently launch modules when available, without reliance on any single nation's budget cycles

The Mars International Space Terminal (MIST)

Crew safety and health remains the primary concern in sending humans to Mars. ISS has provided much useful information about how the human body copes with microzero gravity conditions in confined spaces for long periods — such as loss of bone mass and vision issues — as well as the potential exposure to large does of radiation on site and en route.

More experiments on the ISS, which is now expected to remain in orbit until 2024, could improve knowledge of human health issues for long-term space assignments by males or females, young or old.

A space station orbiting above Mars could continue to expand that knowledge, equipped to deal in real time with medical matters and employing a physician (who might also be a part-time researcher), luxuries a small surface exploration team could not justify.

The components needed to build a robust space station at Mars could be sent into orbit around the planet as they are made, assembled remotely, shielded from radiation and designed for safety, with emergency supplies and systems available whenever humans arrive.

A crew-return vehicle could also be pre-positioned, while smaller missions, some undertaken by private-sector partners, could accomplish a range of complex goals that less frequent, huge and expensive launches could not.

Once completed, the orbiting station, which we dub the Mars International Space Terminal (MIST), could offer a permanent Mars presence and a safe outpost from which to launch activities by more modest, and reusable, shuttles to the Red Planet's surface. [How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic)]

And, critically, crews would be able to control surface robotics and communicate with human explorers on surface missions nearly instantaneously, instead of dealing with an Earth-Mars lag time that can be up to 24 minutes long one-way (depending on the ever-changing positions of the two planets in space).

A new way forward

Prior to permanent residents arriving at Mars, ISS could be used as a platform to conduct the necessary experiments for understanding the construction and assembly of modular structures made of metal, composites, and perhaps carbon composites and nanofibers in orbit around Mars.

ISS partners could gradually shift budgets into the MIST mission portfolio, avoiding a funding hiatus during the transition — and improving the stability of MIST management.

Further, rather than accept that ISS, after decommissioning in 2024, will become a huge piece of space junk — the largest human-made object in space, intended to burn up during re-entry — it could be possible to cannibalize some ISS structures and repurpose them for the Mars orbiting station. After the huge international investment made in ISS (more than $100 billion over the past few decades), it would be satisfying to see efforts made to recoup these costs by recycling some of the ISS structure and components. Meanwhile, safely dismantling ISS could offer lessons in space-debris control, perhaps a future grand challenge for sustainability.

To investigate the prospects of a MIST venture, NASA could convene a meeting of ISS partners to propose a multinational effort to: identify parts of ISS that could be repurposed, advise on methods and techniques to be used to dismantle ISS sections without making extra space debris, and suggest ways to employ unique or dedicated equipment systems from ISS in a potential orbiting Mars station without fitting that station with obsolete or outdated systems.

Recognizing that intense technical, operational, fiscal and geopolitical issues will accompany any U.S. or international effort to construct and operate an orbiting space station around the Red Planet, no crewed mission to Mars will be simple. But the obstacles that have held human exploration back for decades no longer need be the roadblocks they once were.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dr Macdonald is a lecturer at the University of Liverpool, his interests focus on four principal themes: (i) flood and drought frequency; (ii) the reconstruction of long hydrological and meteorological series from multiple sources, including proxy datasets; (iii) development of novel approaches and techniques to better understand and manage flood risk; and, (iv) the implementation of strategic drainage approaches, which focus on the practicalities of interdisciplinary collaboration across traditional boundaries (social, physical and environmental sciences). He has worked within the UK and EU. He current sits on the main committee of the British Hydrological Society and the British Institute at Ankara (British Academy) and is the UK representative on the EU eCOST Floodfreq programme.