NASA's highly anticipated mission to the potentially life-supporting Jupiter moon Europa may not get off the ground until the late 2020s, agency officials say.

Last year, Congress granted NASA $175 million to continue developing its Europa mission, which will perform dozens of flybys to gauge the life-hosting potential of the icy moon's huge subsurface ocean.

In that allocation, Congress declared that NASA must have the Europa mission ready to launch by 2022. But NASA's fiscal year 2017 budget request, which was released Tuesday (Feb. 9), includes just $49.6 million for the Europa effort — a level that, when combined with predicted funding in the coming years, "supports a Europa mission launch in the late 2020s," NASA chief financial officer David Radzanowski said during a news conference Tuesday. [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

Getting the Europa flyby spacecraft ready to launch by 2022 would probably require a 2017 investment of about $194 million (out of a total NASA budget request of $19.03 billion), Radzanowski said. The space agency has provided this estimate to Congress, he added.

"Within our $19 billion request, to find an additional $150 million — whether within the science portfolio or abroad — we felt would upset the balance of the overall portfolio," Radzanowski said. "So we do not think it's prudent to support a 2022 launch at the funding level requested."

Scientists regard Europa as one of the solar system's best bets to host life beyond Earth. The moon's vast ocean — which harbors more water than all of Earth's seas combined — is in contact with Europa's rocky mantle, making possible all sorts of interesting chemical reactions, researchers say.

So astrobiologists are eager to explore Europa — and they're not the only ones. Congress shares this enthusiasm, in large part because of John Culberson (R-TX), who chairs the House of Representatives' Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies, and has a longstanding interest in the search for alien life.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Indeed, in the 2016 budget deal, Congress directed NASA to make its Europa mission more ambitious, ordering the agency to add a component that would actually touch down on the icy moon. The deal also stipulated that NASA use the agency's in-development Space Launch System (SLS) megarocket, as opposed to a currently available booster. (Launching atop the powerful SLS would cut travel time to Europa considerably.)

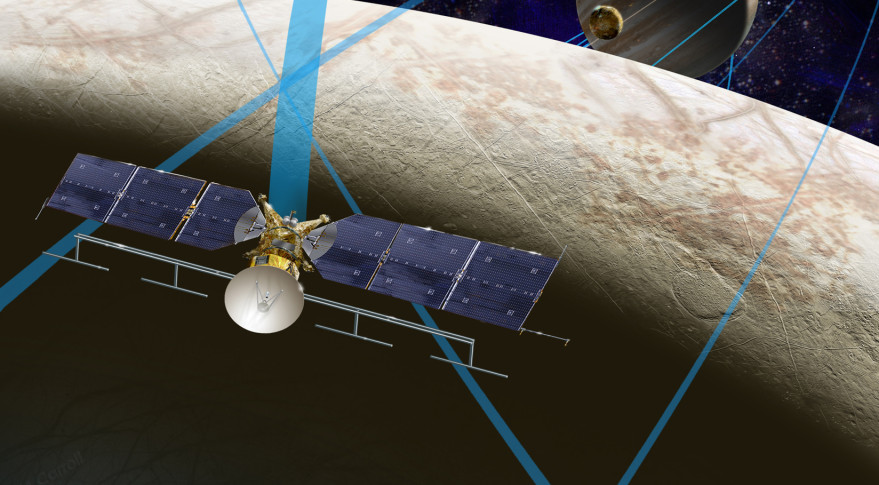

NASA is still assessing how it can incorporate these directives, and how doing so would change the Europa mission's pricetag, Radzanowski said. (The flyby-only version, which would conduct 45 close encounters with Europa from Jupiter orbit over 2.5 years or so, is estimated to cost about $2.1 billion.)

It's too soon to know exactly what's going to happen with the Europa mission, which is still in the early-development phase. For example, Congress may end up giving NASA far more for the project than the $49.6 million it requested this year, bringing a 2022 liftoff back into the realm of possibility.

In fact, that will probably happen, if precedent is any indication. NASA didn't ask for any Europa-mission funding in 2013 or 2014 but ended up getting more than $120 million for those two years combined. And in 2015 and 2016, NASA requested a total of $45 million for the Europa project, and Congress allocated $275 million.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.