Apollo 11 Crew Wrote on Moon Ship Walls, Smithsonian 3D Scan Reveals

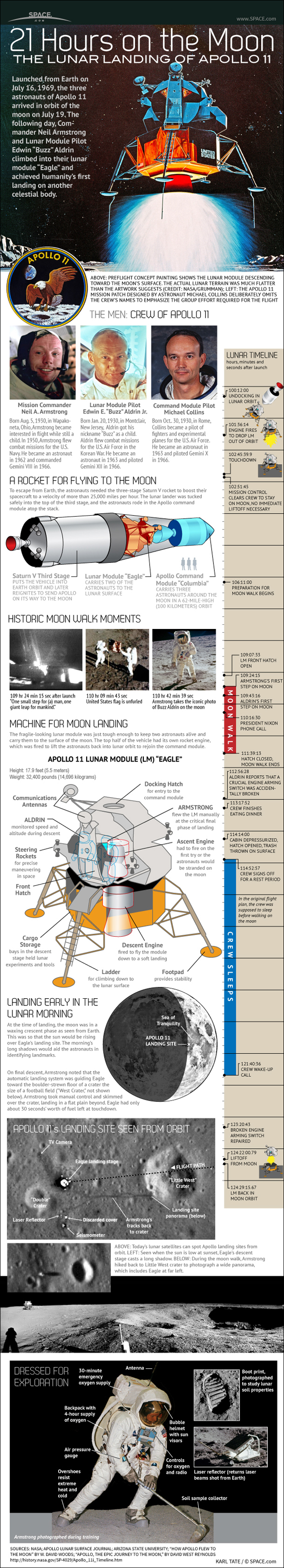

Apollo 11, the first moon landing mission in July 1969, produced a number of iconic quotes, such as, "The Eagle has landed," and "That's one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind."

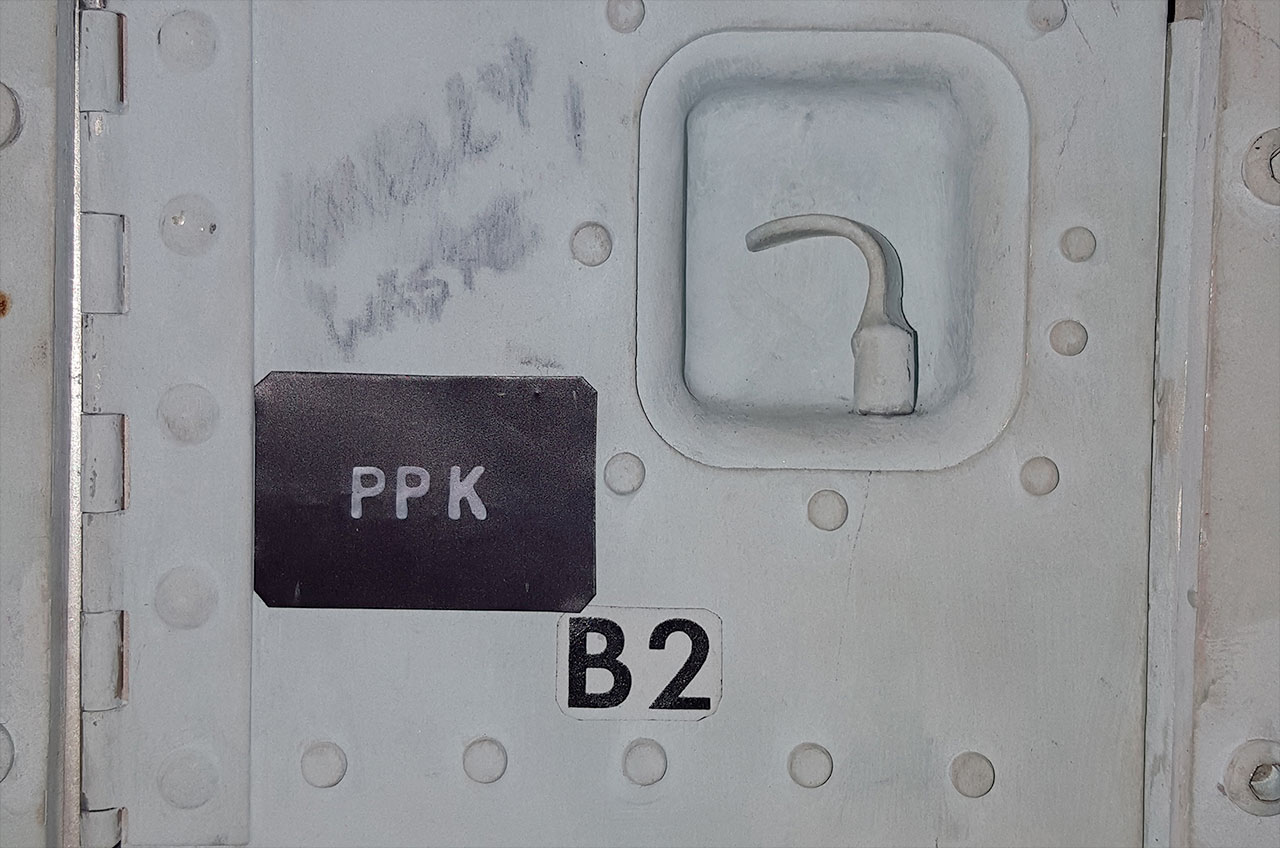

Now, thanks to a surprising discovery by the Smithsonian, history can possibly add "Smelly Waste!" to that list.

Curators working at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. uncovered the short but perhaps notable quip, among other unexpected inscriptions, written on the walls inside the Apollo 11 command module, Columbia. [The Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures]

"By writing 'Smelly Waste!' on there, we presume that [the astronauts] were warning themselves they probably should open this locker again at their own peril — and probably leave it closed," said Allan Needell, a curator in the space history division at the museum.

The olfactory warning, along with a hand-drawn calendar and navigational notations, were found during the first 3D scan of the historic spacecraft, which flew Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the moon and back.

Skinless scanning

For the past 40 years, the Apollo 11 command module has been on display at the National Air and Space Museum in a plexiglass skin. The covering protected the capsule from the public's hands, but also precluded curators, historians and researchers from accessing the inside of the vehicle.

That changed last year, when, as a part of a still on-going renovation of the museum's main gallery, the decision was made to move Columbia from the Milestones of Flight to a new exhibit hall, "Destination Moon," opening in the 2020 timeframe. In preparation for its eventual new display, the capsule was removed from its angled stand and its plastic skirt was removed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This has provided access to it that really none of us have ever had," Needell said in an interview with collectSPACE.com.

At the same time, the Smithsonian's Digitization Program Office was looking to identify iconic objects that would be useful to 3D scan. The project, which seeks to extend the public's access to historic artifacts by bringing them online, had previously documented the Wright Flyer airplane, also at the National Air and Space Museum, but Columbia is the first spacecraft to be imaged inside and out.

"We thought this would be a very, very good thing," stated Needell.

The project uses new software and techniques to produce a very detailed 3D model, stitching together data collected from multiple sources, including laser measurements and high resolution photometry. The result is not just a model that the public will be able to access at the museum, online and possibly even through VR headsets, but also of value to researchers.

But to create the model, the digitization program needed to be able to go inside Columbia and that meant figuring out what was safe to do and what was not.

"We tried to determine how to provide the most possible access to the data collecting technology, but at the same time, protect the object and not damage it," said Needell. "We decided that [the people collecting the data] could not get in and sit in the seats, for instance, nor could they build a platform to put scanners physically inside the command module."

So instead, workarounds were developed, using booms for example, to introduce the equipment into the spacecraft.

Writing on the wall

Needell and his team also decided that they would provide access to the lower equipment bay, the area located below the astronauts' seats, which housed the ship's navigation sextant, telescope and computer. [Lunar Legacy: 45 Moon Landing Moments in Photos]

"No one from the Smithsonian, as far I knew — not as long as I've been the curator for 20 years, has ever been below there to document the conditions or any of the aspects of the lower equipment bay," said Needell. "We've been able to sort of see above the seats, but that's about all."

So, for the first time, the curators removed from the lower bay the large bag that held the Apollo 11 crew's pressure garment assemblies — in other words, their spacesuits — as well as several helmet bags and a checklist pocket that command module pilot Michael Collins used while orbiting the moon alone.

And then they saw it, the literal writing on the wall.

"On a panel to the left of the navigation station, there were numbers," described Needell. "Right now, I'm working with [other historians] to try to describe at just what point in the mission these were written down and what was going on."

Believed to be in Collins' handwriting (though when he was contacted recently by Needell, Collins said he did not have recollection of the inscriptions), the numbers may correlate to data that was radioed by Mission Control to Columbia's pilot as he tried to pinpoint the lunar module Eagle on the moon's surface below.

Other writings discovered in the command module, like the "Smelly Waste!" note, seem to indicate some improvisation by the crew. The pre-launch stowage lists indicate that the stinky locker had been where the personal preference kits (PPKs) — the astronauts' mission mementos — had been packed for the flight.

"We can trace later that they moved the PPKs to another location and they put in, well, one can only speculate what was there, but maybe a damaged fecal containment bag. We don't know," said Needell.

On the subject of stowing waste, near another locker is the note, "Launch Day Urine Bags." The curiosity with that find is that there was no indication in the pre-launch checklists for such an accommodation.

"There is a device for venting into space excess water, the urine dump," explained Needell. "But clearly you can't use that pre-launch. So probably, and this is just speculation, that if they actually had to use a urine bag during the pre-launch period, this was where they needed to put it."

Tracking the days

And then there is the calendar.

At some point during the flight, one of the astronauts drew a small calendar on the wall below one of the lockers.

"We are still trying to figure out on this calendar when and who would have drawn it," Needell described. "Why would someone have put this checkbox and checked off day by day on the wall?"

"Every box, from [July] 16th through the 23rd is checked. The 24th [landing day] is written in numerically, but is not checked." he added.

Needell has begun looking through the mission photos and television broadcasts for possible clues. A mid-mission TV report filmed by the crew may show the calendar had yet to be drawn. A post-landing photo, that shows a technician working inside the command module, reveals it there, just as it appears today.

"We are speculating that it was Mike, when he was alone [in lunar orbit]," Needell said. "You think about the human instinct to do that kind of thing, like somebody in a prison cell or prisoner in a war camp. Mike was this 'loneliest man in the world' on the far side of the moon, and so maybe he decided to do it."

There even is a piece of plastic taped over the calendar to protect it from smearing, as some of the other writings (like the "Smelly Waste!") did.

"It looks like at some point somebody realized that it was going to be smeared and found a piece of plastic sheeting, cut it and taped it over. It looks like the lower left corner of the tape had been folded up and opened, so my guess is that they did that and then lifted the tape and sheeting to do the crossing out [of the date]," said Needell, implying that the covering was the astronauts' own doing in-flight.

Bringing Columbia to life

The newly-discovered writing was not the first to be found in Columbia. Collins, now rather well known, inscribed the wall of the command module after splashdown with, "The Best Ship to Come Down the Line, God Bless Her."

But that epitaph (of sorts) was commemorative in nature. The writings near the lockers and in the lower equipment bay were part of the historic flight itself.

"It kind of brings to life the command module and shows there were people in there dealing with human-type issues as they were trying to carry out this mission," Needell said. "You can see in detail that this object is not just a machine like any of the others."

"It has unique things because it participated in the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission," he said.

And the exciting thing is that there still may be even more to be learned, even almost 50 years after Apollo 11 ended. An online version of Columbia's 3D model is expected to be available by July, the 47th anniversary of the mission.

"There is a lot that if we can crowd-source I think will be fascinating," Needell remarked. "It seems to me, there are people out there who are just terrifically good at some of the details and we'll be able to share this data and let them be able to do that kind of work.”

Preview the Smithsonian's 3D scan of the Apollo 11 command module, Columbia, and see more photos of the writing found inside at collectSPACE.com.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2016 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.