After zipping around Earth for nearly a year, NASA astronaut Scott Kelly must now get used to living on the planet's surface again.

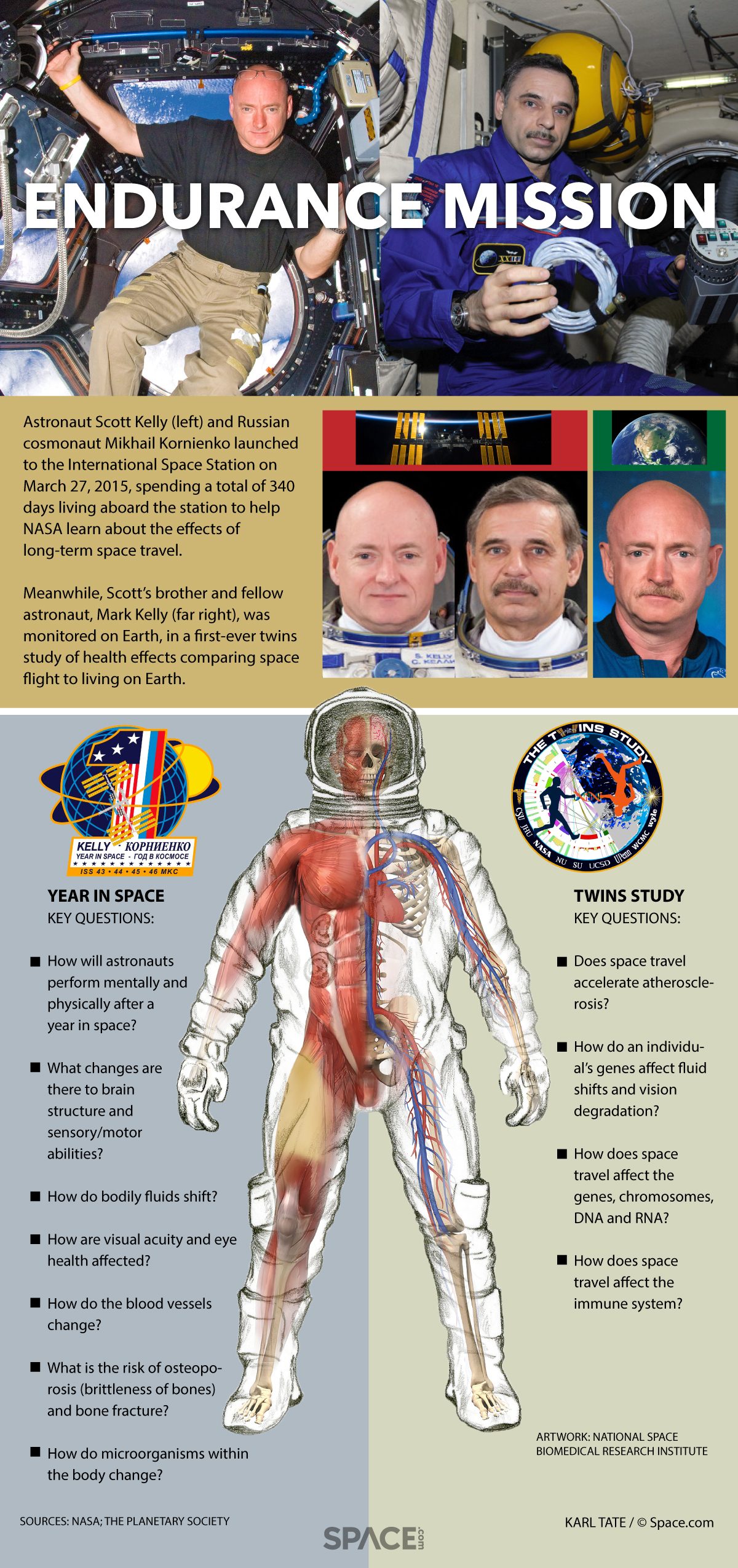

Kelly and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko returned to Earth with a landing on the steppes of Kazakhstan late Tuesday (March 1), ending their unprecedented 340-day stay aboard the International Space Station.

Shortly after landing, both spaceflyers — along with cosmonaut Sergey Volkov, who also came home, but after the typical, 5.5-month station mission — were taken out of their Soyuz spacecraft, placed in chairs near the landing site and taken into a medical tent for an hour-long "field test" to assess their general condition. [Welcome Home! Landing Photos for 1-Year Astronaut Scott Kelly]

That test consists of a variety of experiments, Kelly said late last month in his final conversation from the space station with reporters.

"Some are physical — kind of like even an obstacle course, where you run around obstacles and stand up from a sitting position, and jump and stand," he said.

The spaceflyers then went their separate ways, with Kornienko and Volkov headed to Moscow and Kelly to Houston, where NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) is located.

NASA astronauts just back from an ISS mission undergo several hours of medical tests at JSC, Kelly said. They then generally complete a 45-day "reconditioning period," to build up bone mass and muscle strength lost in the microgravity environment of space, said Stevan Gilmore, the lead flight surgeon for Kelly's one-year mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There are daily workouts and exercises to make sure that we return the crewmember back to the same kind of functioning that they had before the mission started," Gilmore said last month during a NASA TV interview with NASA spokesman Dan Huot.

Even though Kelly stayed aboard the International Space Station for twice as long as crewmembers usually do, the current plan is to put him through the standard 45-day reconditioning program, Gilmore added.

"We do have the latitude, in the case that a little bit more time is required for the rehab process — we can extend that if necessary," Gilmore said. "But I anticipate that it'll look in many ways similar to the six-month experiences that most of the station astronauts have."

The main goal of Kelly and Kornienko's mission — a joint effort involving the United States and Russia —is to better understand how astronauts cope physiologically and psychologically with long-duration spaceflight. This information should help mission planners map out future crewed journeys to Mars, NASA officials have said. (The space agency aims to get astronauts to the vicinity of the Red Planet in the 2030s.)

Kelly and Kornienko are participating in 17 different experiments related to the one-year mission, said John Charles, the chief scientist of NASA's Human Research Program. And those experiments aren't over just because the spaceflyers have landed.

Indeed, Charles said, many of the duo's blood samples won't even come down to Earth until next month, when the samples are scheduled to land aboard SpaceX's robotic Dragon cargo capsule. Furthermore, researchers will be tracking Kelly and Kornienko's progress for a while even after that happens.

"There's months and months of post-flight data collection," Charles told NASA spokesman Gary Jordan during an interview on NASA TV last month.

"In some cases, up to nine months after landing, we're still acquiring samples of the astronauts — perhaps even longer, as they return to their normal duties and we acquire data from their annual physicals and so forth," Charles added. "And then the data analysis really begins."

Some of this analysis involves comparing Scott Kelly to his identical twin brother, Mark, himself a former NASA astronaut. Mark stayed on the ground during the yearlong mission and serves as a control, to help researchers identify any genetic changes spaceflight induced in Scott.

Scott Kelly said during his last in-space news conference that he has been experiencing some issues with his vision, a common occurrence among astronauts. However, while scientists will ultimately have the last word on how the 340-day mission affected Kelly, the astronaut said he's doing all right.

"Physically, I feel pretty good," Kelly said.

The nearly yearlong mission, while unprecedented for the ISS, did not set the record for most time spent in space continuously. Cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov earned that distinction, living aboard Russia's Mir space station for more than 437 days, in 1994-95.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.