Subaru Telescope Tour: A Journey to the Top of the World

On the summit of Hawaii's Mauna Kea sits Japan's premier instrument for viewing the universe in optical and infrared light: The Subaru Telescope.

Subaru is a 26.9-foot (8.2 meters) instrument that bears the Japanese name for the cluster of stars known as the Pleiades.

In December 2015, I joined several astronomers in taking a tour of the enormous telescope, which sits high above the island state. [See more photos from our Subaru Telescope tour]

The road to Mauna Kea

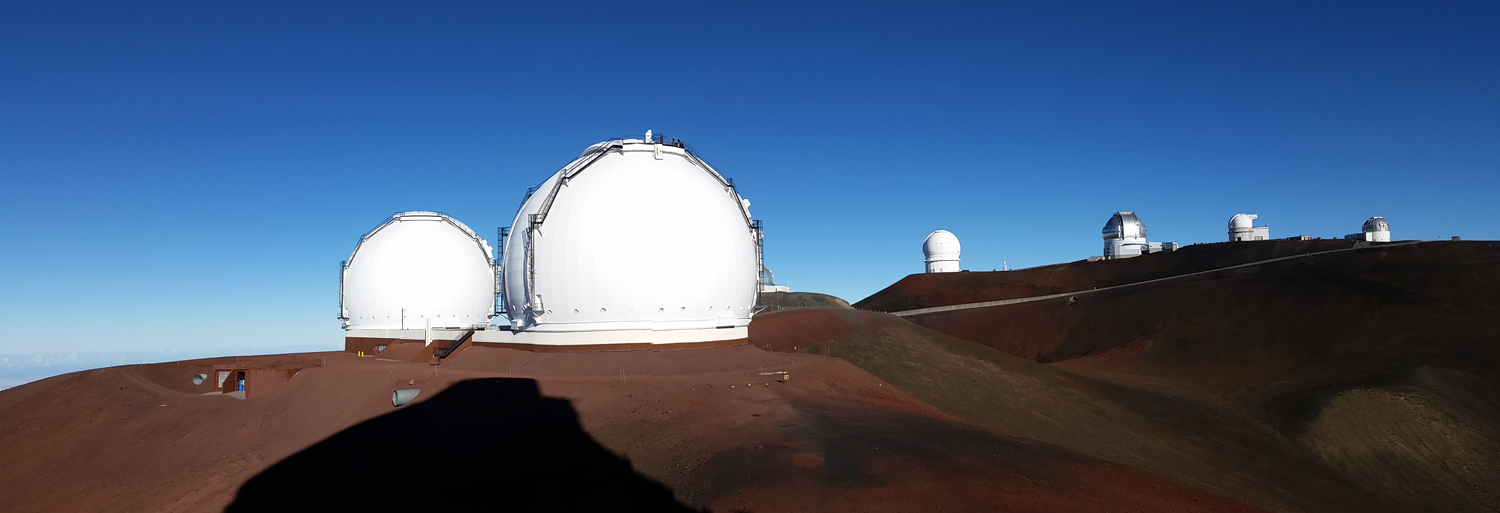

Once an active volcano, Mauna Kea hasn't erupted in about 4,5000 years. The peak of the mountain is the highest point in the state of Hawaii. Although Mauna Kea hosts 13 advanced telescopes that probe the outer edges of space for astronomers and astrophysicists, the dirt road to reach the observatories felt like a throwback to another generation, when paved roads were few and far between. Being dragged over a washboard seemed like a more pleasant alternative.

Saddle Road, which crosses from the east to the west side of the Big Island of Hawaii, doesn't rise far above sea level. It isn't until you reach the turnoff for the mountain that you start to climb. The Maunakea Visitor Center, operated by the University of Hawaii, sits at 9,300 feet (2,800 meters), and is reachable by many types of vehicles. Once you leave Saddle Road, the path to the peak becomes perilous. Only four-wheel-drive vehicles are permitted to ascend. The primary reason for the precaution has more to do with the amount of dust kicked up, our tour driver told us; a two-wheel drive vehicle can stir up enough dirt to obscure the instruments' ability to probe the heavens above. Still, I wasn't altogether convinced that that was the only reason; the ungraded dirt road was extremely rough and windy, and not one that I would have cared to attempt on my own.

When we left the Visitor Center, scattered plants were visible. But once we began the trek up the mountain, the terrain outside seemed more Martian than terrestrial. The ground was red and rocky, and no vegetation was in sight. As we crawled slowly over the road on a half-hour-long journey, we seemed to be the only life for miles — not necessarily a bad thought, since I was hoping we wouldn't have to pass another car on the narrow trail. Winding around the top of the mountain, the domes of the observatories slowly rose to greet us.

The Subaru Telescope, operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), sits at an elevation of 13,579 feet (4,139 m), on the highest peak in Hawaii. Before we began our trip, we had to sign a waiver acknowledging the potential danger of the ascent (no scuba diving 24 hours before or after climbing!). We spent an hour at the Visitor Center to become acclimated to the slight change in elevation before continuing up. We were warned about altitude sickness in a lecture before we ascended, and at the peak we were reminded to let our guide know if we felt dizzy, nauseous or had headaches.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This wasn't just due to our visitor status. Our guide, Nemanja "Nem" Jovanovic of the NAOJ, told us that when he made his first trip up, he noticed that it took him three or four attempts to perform simple tasks correctly.

"The best way to be up here is to not trust yourself. Always second-guess everything," Nem said. "The more cocky you are, the more likely you are to screw up."

When he works with Subaru's instruments, Nem wears an oxygen tank to help him stay sharp and focused. And he's not the only one. During the tour, I noticed oxygen canisters placed throughout the observatory, each as clearly marked as fire extinguishers. Partway through the tour, I also noticed that my fingers had started to go numb, making note taking more challenging. It was only then that I realized that Nem was wearing thin gloves to keep his hands warm.

Nem has been working at Subaru for more than three years. He lives in the town of Hilo, and makes the hour drive up to the observatory every few months. While on site, he stays at the visitors' quarters, located near the Visitor Center. He'll come up about a week before the observing run "because our instrument needs some pampering," then stick around through it.

His longest run was 23 days. He explained that there's no limit to the number of days you are allowed to work, but Subaru management limits you to 14 consecutive hours a day on the peak.

'The prettiest telescope'

Construction on the Subaru Telescope wrapped up in 1998, and its first scientific images were released in early 1999.

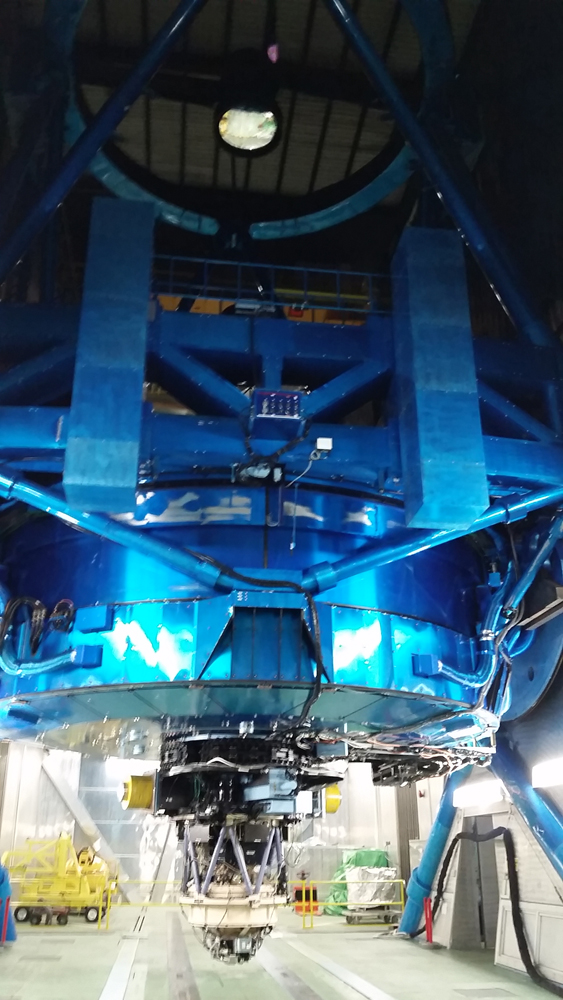

The enormous telescope stands in the center room of the observatory, which opens outward. We stood beneath the behemoth instrument, peering upward at the mirrors that rose above us. The telescope is bright blue, leading Nem to dub it "the prettiest telescope."

Unlike most other observatories, Subaru's instruments are located in other rooms (separate from the telescope itself). Since the telescope's room opens up to the outside, this keeps the expensive instruments protected from dust, wind (which can reach speeds of 100 mph) and extreme temperatures. A series of vent rooms surround the outer walls of the observatory and run through the building, keeping the temperature of the instruments the same as the telescope. At nighttime, these vent rooms open automatically. Sometimes, at night, Nem said he comes down from observing and stands in one of these vent rooms to look outside.

Subaru contains 13 instruments that enable the telescope to observe cool interstellar dust, observe faint objects and search for things like the presence of the solar system's proposed "Planet Nine."

"It means we have more instruments than we know what to do with," Nem joked.

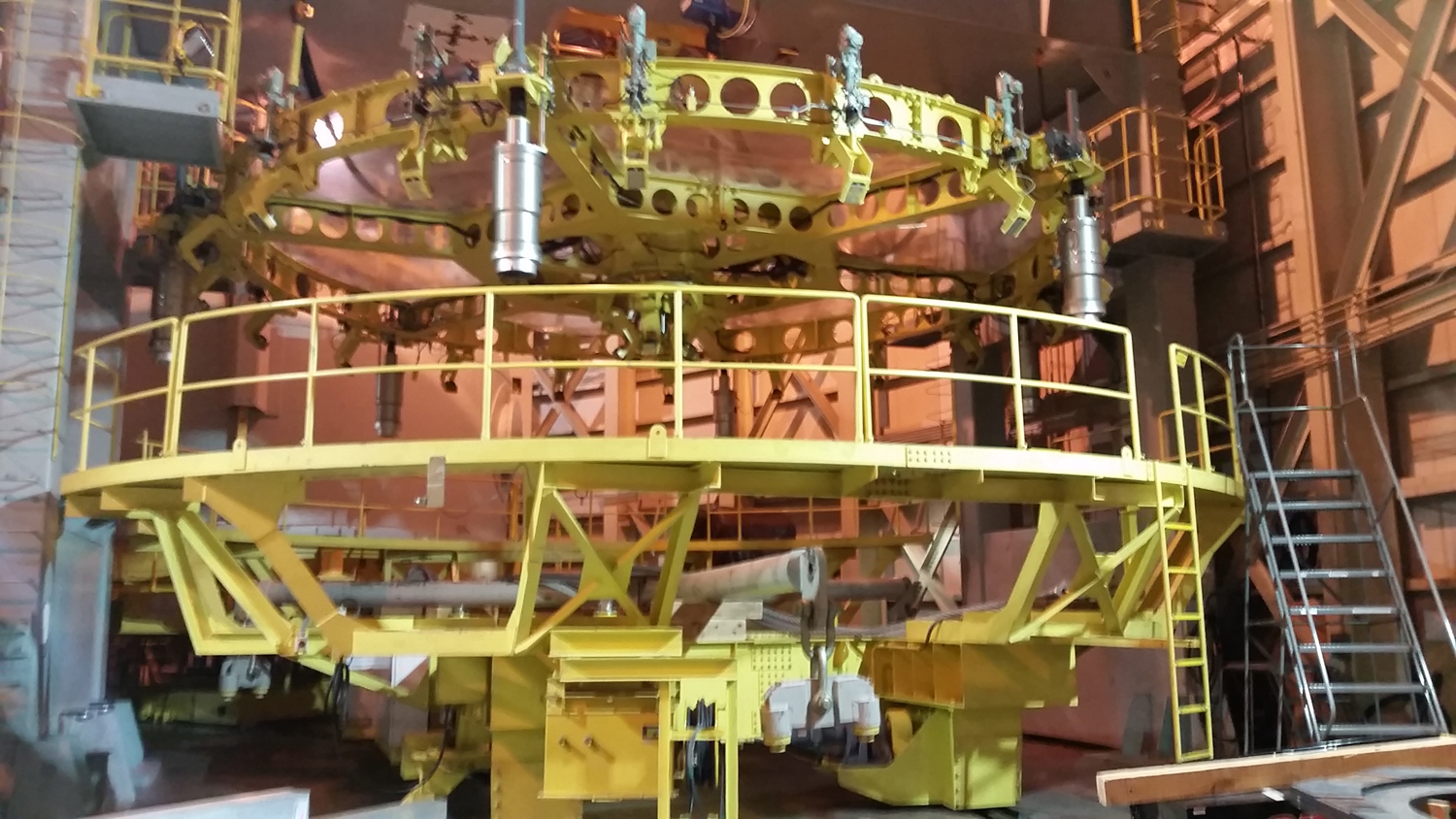

Three of the instruments are known as Cassegrain instruments, which change the location of the telescope's focal point, and are kept in a storage room connected to the telescope room. A vehicle that runs along one of the many tracks in the floor is used to change them out. The instruments themselves are mounted on a revolving carousel, which Nem likened to one found in a six-shooter gun.

When a new Cassegrain instrument is placed on the telescope, the custom-built cart picks it up and carries it beneath the telescope. The instrument is then jacked up to the telescope, where it can be secured.

"It's a really simple system for swapping out instruments," Nem said. "There's no craning needed."

But some of the instruments go on the top end of the telescope, and those do require heavy lifting. A crane comes in and hoists the instrument currently on top of the telescope, while operators disconnect it. Two drivers work the crane; one drives it and the other adjusts its alignment with the telescope.

"It's a pretty scary thing when you've got a 7-ton instrument over the mirror," Nem said.

The crane then moves the instrument into the storage room for top-end units, where it is swapped out for another one. The new instrument is hoisted onto the telescope and connected. This happens about twice a month, Nem said. If everything goes smoothly, the swap can take a full day. With minor technical problems, Nem said it can extend the changeover to three or four days.

Things don't always go smoothly. Not long ago, one of the sensors on the crane was off by a very little bit, and the instruments bumped into each other, precipitating an immediate shutdown. After that, the top-end instrument couldn't be changed for two months.

During the instrument exchange, Nem said the crane driver wears an oxygen mask. Whether or not other members of the team carry a tank is up to them; some do and others don't.

"But they work up here a lot more than I do," he said. Members of the technical staff are present on the mountain seven days a week, 365 days a year.

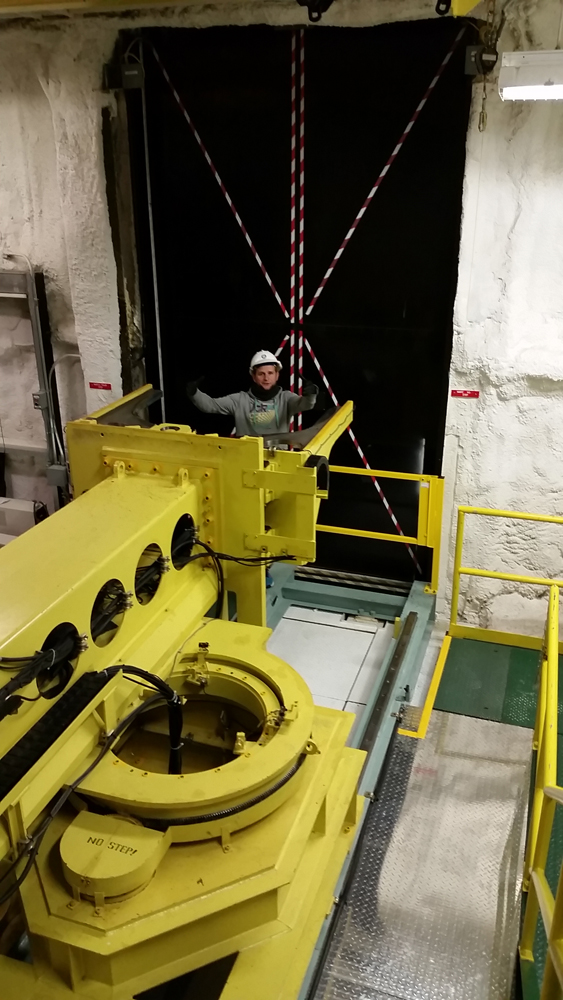

Every two or three years, the primary and secondary mirrors of the telescope are removed to update their aluminum coating. An 80-ton crane lifts the primary mirror from its place and sets it in a cradle below. The cradle descends through a round hole in the floor to the mirror recoating room, which you see when you walk in the entrance. The cradle is pushed on rails running around the floor. A sprinkler system from above rains acid down on the mirror, which dissolves the aluminum coating, and a new coating is applied. The entire recoating process takes two to three weeks, and technicians use the time to overhaul the rest of the telescope as needed.

The instrument storage room was amazing to see. Not only was our group able to examine the outside of the various instruments, Nem also invited us to lie on the floor and look at the mirrors from below. Despite the chilly concrete floor, I wasn't about to miss the chance. While trying to find the best perspective to capture the mirror, I realized that I was in position to take the world's best selfie.

"Does it make you look fat or skinny?" Nem asked from above.

"Well, I like it, so, skinny," I responded.

When I attempted to scoot out from beneath the telescope, Nem reached out nervously to make sure I didn't smack my head into the $10 million lens, making me question the wisdom of my decision after the fact. [10 Biggest Telescopes on Earth: How They Measure Up]

On top of the world

After our tour of Subaru, Nem led us out on the catwalk to see the view. Observatories abounded at the top of the peak. I spied the twin domes of the Keck telescope when I stepped through the door. I caught a glimpse of Gemini North Telescope. On the other side, I could see the movable dishes of the Smithsonian Submillimeter Array.

Off in the distance, marked only by a lone construction truck, was the intended site of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), the latest source of contention on Mauna Kea.

"Come back in 10 years' time, and you can take a before and after picture," Nem said.

Then, considering the recent delays (I made my visit the same day that Hawaii's Supreme Court ruled against the legality of TMT's building permits, though the announcement wasn't made until later in the day), he added, "Although, at the rate they're going, come back in 10 years and it will still be the same."

But the observatories weren't the only sight to see. From the peak, we could see one of the peaks rising above the island of Maui. Clouds around the base of Mauna Kea blocked the view of most of the Big Island, making it feel like we were isolated from the rest of the world.

By the time we returned to our vehicle to descend, I was feeling chilly, even through my jacket. We passed back through the clouds to the roads below. But glancing back, I thought I saw the light winking off one of the many telescopes on the peak — instruments that will continue to study the stars above for decades to come.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd