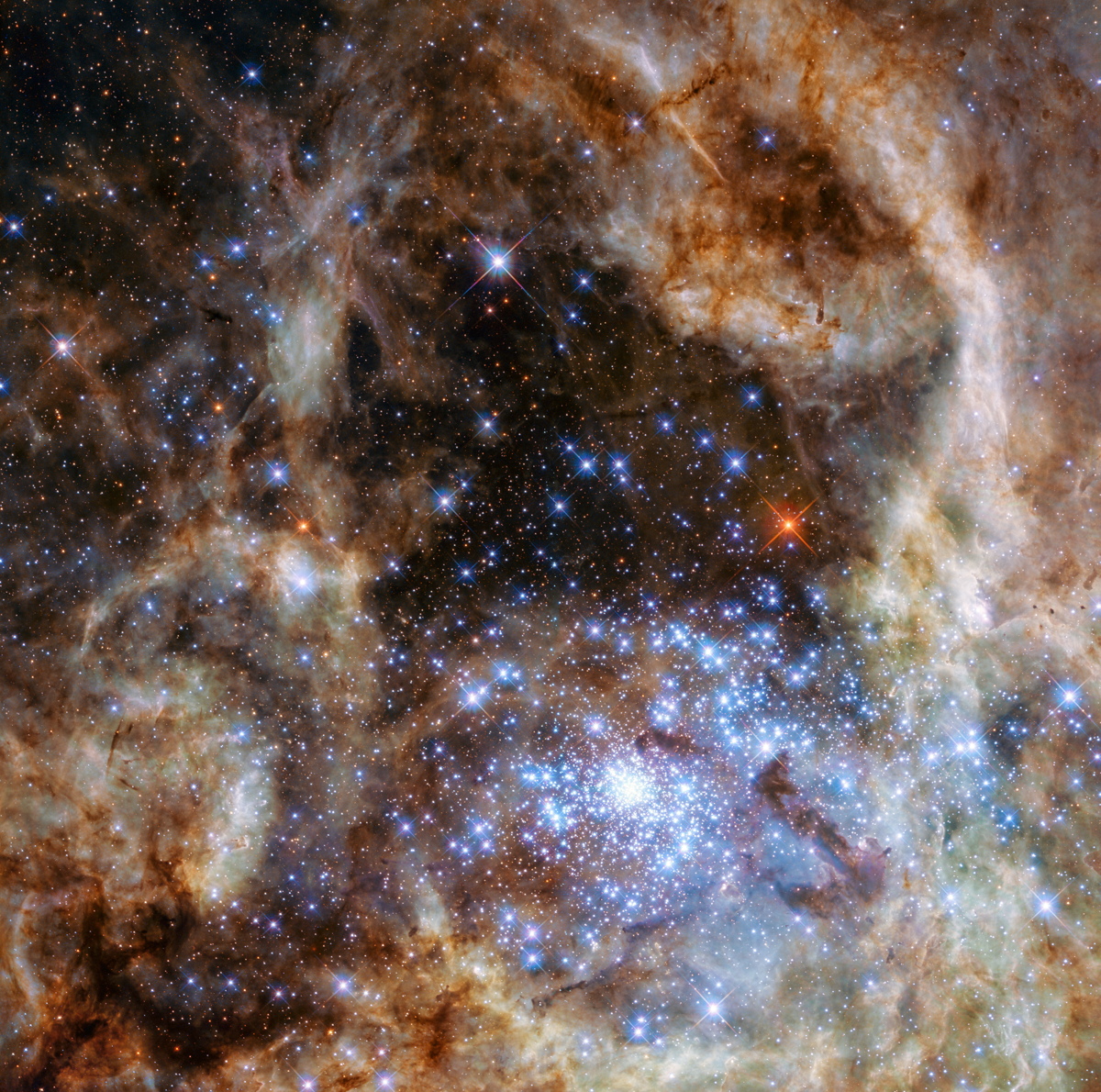

Some of the biggest and brightest stars in the universe are packed within a single cluster, a new study reveals.

Researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to image the young star cluster R136 in ultraviolet (UV) light for the first time. The cluster is located in the Tarantula Nebula of the Large Magellanic Cloud galaxy, about 170,000 light-years away from Earth.

The scientists were hunting for very big and very hot stars, which radiate most of their energy in the UV range of the spectrum. And the researchers hit the jackpot, spotting dozens of stars within R136 that are at least 50 times more massive than the sun, and nine that harbor more than 100 solar masses. (One of these giants, the previously discovered R136a1, is the largest known star in the universe, at more than 250 solar masses, NASA officials said.) [Celestial Photos: Hubble Space Telescope's Latest Cosmic Views]

![Find out how Hubble has stayed on the cutting edge of deep-space astronomy for the past 20 years here. [See the full Hubble Space Telescope Infographic here.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/qK2xWDesnWUEsoFccAR7pM-320-80.jpg)

These behemoths are extremely luminous as well as extremely large; together, the nine biggest ones are about 30 million times brighter than the sun, researchers said.

The sheer abundance of these giants in R136, which is just a few light-years wide, should help astronomers better understand how the massive stars form, study team members said.

"There have been suggestions that these monsters result from the merger of less-extreme stars in close binary systems," co-author Saida Caballero-Nieves, of the University of Sheffield in England, said in a statement.

"From what we know about the frequency of massive mergers, this scenario can't account for all the really massive stars that we see in R136, so it would appear that such stars can originate from the star-formation process," Caballero-Nieves added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers also determined that these enormous stars lose mass extremely quickly over the course of their brief and dramatic lives (which often end with the stars collapsing to become black holes). The stars eject up to one Earth mass of material every month, at speeds that can reach 1 percent the speed of light.

The new study will be published in the monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The Hubble Space Telescope, a joint project involving NASA and the European Space Agency, launched into orbit in April 1990 with a slightly flawed primary mirror. Spacewalking astronauts fixed the problem in 1993, and upgraded the observatory several more times over the years, with the last servicing mission launching in 2009.

The telescope continues delivering important science, and jaw-dropping images, to this day.

"Once again, our work demonstrates that, despite being in orbit for over 25 years, there are some areas of science for which Hubble is still uniquely capable," study lead author Paul Crowther, also from the University of Sheffield, said in the same statement.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.