'Abandoned in Place': NASA's Decaying Spaceflight Facilities Preserved in Photos

In his new book "Abandoned in Place," photographer Roland Miller takes readers on a visually stunning, emotionally charged tour of various abandoned facilities connected to NASA's space program, including now-unused launchpads and retired science facilities. Miller's images highlight the age and decay of these locations, but also forge a connection to their past lives.

Miller spoke with Space.com about how he first began photographing these sites more than 30 years ago, and what he hoped to convey with his particular approach to this visual documentation. In addition to the photographs, the book includes essays by Miller, and people connected to the various sites.

"I always joke with people that [if it weren't] for the fact that I wear glasses and about 40 or 50 IQ points, I'm sure I could have been an astronaut," Miller told me when I asked him about his connection to NASA and space exploration. [Stunning, Tragic Images of Abandoned Space History (Photos)]

Now a dean in the Communication Arts, Humanities and Fine Arts Division at the College of Lake County in Illinois, Miller taught photography for 22 years. He insists that photographing abandoned sites is a "side project" and a "hobby," and that he is neither a historian nor the kind of space enthusiast who can "name every astronaut who ever flew."

But Miller is a child of the Apollo era, and like many people his age, he has a deep sentiment for human spaceflight. And also like many others, he mourns the loss of the way NASA pushed boundaries when he was young. (You can read more about his thoughts on this in the op-ed he wrote for Space.com).

"Growing up in the 1960s … it was just such a fascinating time and such a unique experience," Miller said. "In the mid- and late '60s, there were a lot of awful things going on. Vietnam was in full swing. The civil rights movement was well on its way to making the changes it finally has made, but you know there was quite a bit of struggle that had to go on. The assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King in 1968. The riots in Chicago in 1968. There was a lot of tension in America at that time, and the space program was a shining example of what we could do if we really set our hearts and our minds to a gargantuan task. And I think, as we move farther from that, that accomplishment is only going to seem more and more impressive."

Miller moved to Florida in 1984, and shortly after arriving, he was asked to come out to NASA's Kennedy Space Center to help dispose of some old photo-developing chemicals. His guide at the facility offered to take him over to Launch Complex 19, the site of the Gemini crewed-vehicle launches in the 1960s. The complex was no longer in use, and stenciled on a concrete pillar was the phrase "Abandon in Place," which indicates that a site is no longer expected to be up to code. Miller was fascinated by what he saw. Around 1990, he approached NASA about a larger project to photograph more of the agency's abandoned launch sites and facilities.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I'm a photographer — I like to make photographs, so [early on], it was really about making the photographs, and I hope I exhibit that," Miller said. "And then, I fairly quickly started to realize that this was a fairly unique opportunity I had. And, in part, I felt I had a great responsibility, because I don't think anyone has photographed at Cape Canaveral as much as I have.

"And it was obvious from the start that NASA wasn't going to be able to preserve these sites, because they're right on the ocean, and the salt water environment [causes things to] rust away," Miller continued. "It's a constant battle to keep that steel from rusting. So it was pretty obvious these were not going to be sites that could be preserved long-term. So I thought that photography was one way to preserve them and show the evolution of how time affected them."

The chapters of the book are divided by era or program, starting with facilities that hosted the early rocket tests, such as the Navaho Launch Complex 9 at Cape Canaveral. Miller's photos of Complex 9 show vines swallowing up stairways; the weathered paint on a group of electrical panels that has peeled away into a colorful abstract pattern; and massive metal bolts on which lives might have once depended, which are now rusted a deep red.

"[This work] does show the temporal nature of life," Miller said. "It does show the aging. It does show how something that was once the focus of the world's attention can, only a few years later, become completely obscure and out of touch with what's going on contemporarily."

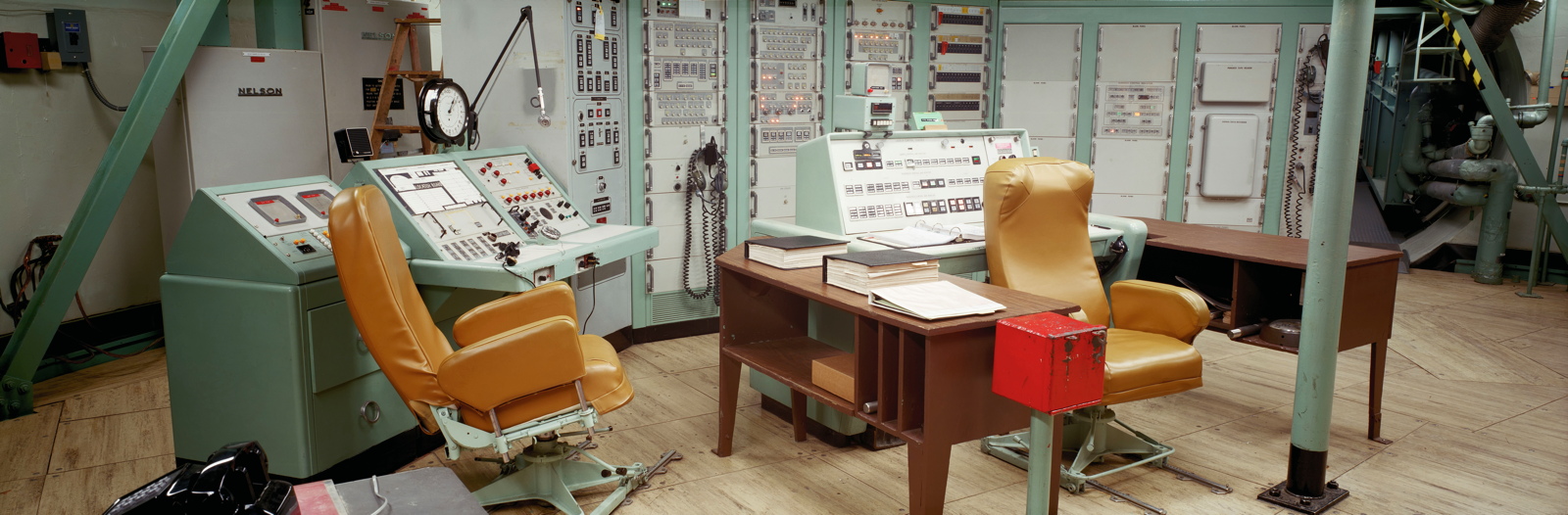

Some of Miller's photographs impart a certain sadness — the locations from which humanity first escaped the clutches of gravity look like ancient ruins. But for the most part, Miller avoids that sadness. Instead, he photographs the structures with great dignity, capturing their awesomeness, even if it lies under a layer of rust and decay. Miller doesn't forget that these structures and facilities are still examples of great engineering and construction.

"There are visual references to other archaeological sites, like the great pyramids," Miller said. "I see things that remind me of Mayan ruins, of Greek ruins, of Anasazi Native American ruins in the southwestern United States. There are so many visual references to those types of sites that, once I started seeing [them], I was trying to connect that."

"Because [the sites in the book] really have become archaeological sites in many ways, and I think, just at a base level, I was just trying to preserve them in this state of their existence," he added. "There are obviously thousands of photographs of these facilities while they were active. I wanted to show how they've evolved and what had happened, and I do think there is that sense of loss."

Many of Miller's images try to convey the massive scale of these former launch sites and facilities, and those images cannot help but simultaneously illustrate the desertion that surrounds these locations. There are no cars, no lights on; and weeds poke through the cracked pavement. But more of the images in the book focus on smaller details. They closely examine the decay that is taking place, and frequently capture the unintentional beauty that has arisen from that decay.

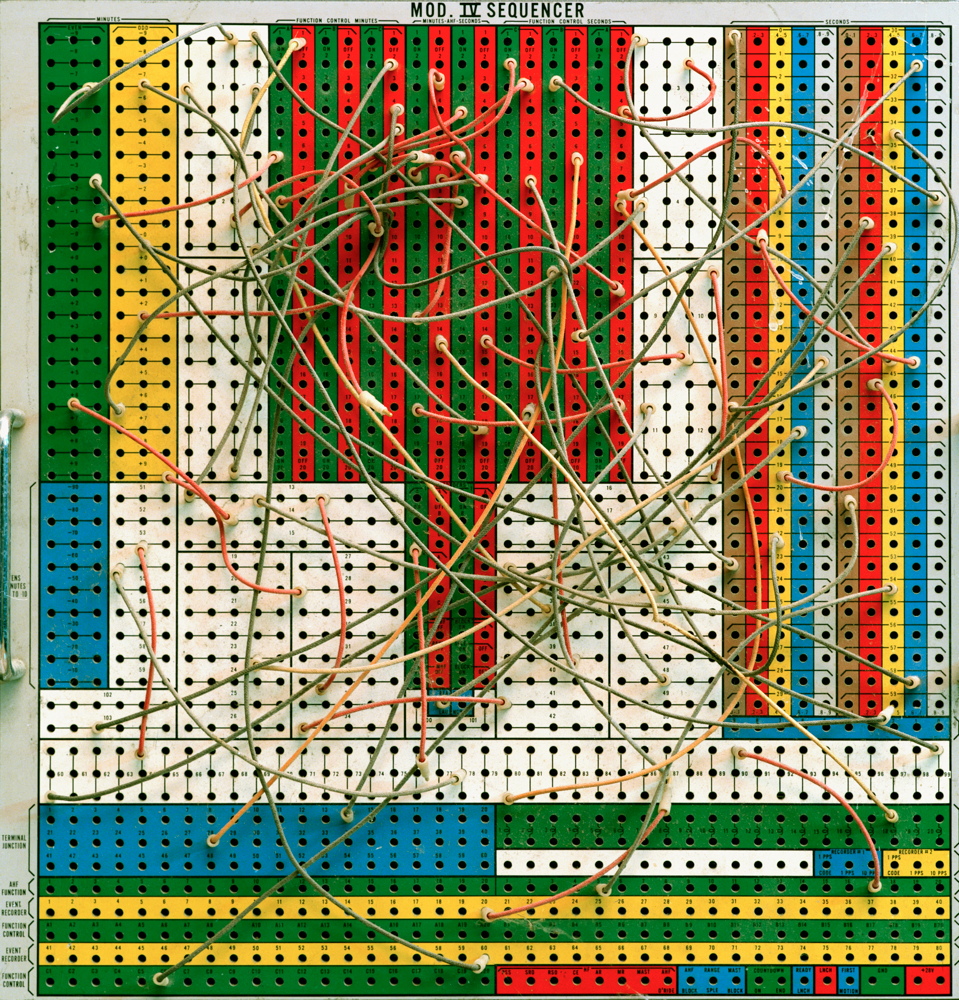

One photograph zooms in on a "plug board" (it looks sort of like an old telephone switchboard, with wires connecting different peg holes in some indecipherable pattern) from the Redstone Launch Complex 26 Blockhouse. It's framed so that nothing else around it can be seen, and it's easy to imagine the people who focused so intently on it, and arranged those wires in just the right way. It looks frozen, rather than abandoned, like someone's hand might move into view at any moment and move one of the cables.

"I took what I refer to as a dual approach to the subject matter because, at some level, it has to be documentary in nature," Miller said. "There are a lot of overall shots where you see the whole pad or good portion of the structure, but I also wanted to photograph the nuances, the smaller details, the more abstract things, if you will — things you wouldn't necessarily notice.

"I think, when people think of a launchpad; they think of the whole thing," he said. "They think of the tower and the mobile service tower, but they don't really think about the details. So, to tell a fuller story, I made a very concerted effort to [do that]. Plus, there are so many visually interesting things going on when you get down to that detail level. It's actually one of the unusual things about the project … People tend to do one or the other, not both. And I took some grief at the beginning of the project for doing that, and I'm glad I stuck with it because I think it's one of the more important aspects of it."

Paired with the photographs are essays by Miller, as well as a handful of essays written by people with very different connections to the space program.

"I approached quite a number of people I knew in the space industry — and I guess it was one of the happy accidents, because these were the folks that responded and said, 'Yeah, I'd like to do that,'" Miller said.

"I think it actually fit very well with the flow of the book to have an art historian write the introduction and kind of describe the history of space and art," Miller said, referring to Betsy Fahlman, a professor of art history at Arizona State University. Craig Covault, an aerospace journalist who has "covered every U.S. space launch since Apollo," according to a statement from the book's publisher, wrote an essay about Launch Complexes 40 and 41, two locations that had great significance in the early days of human spaceflight and that have been repurposed for new phases of human spaceflight.

Col. Pamela Melroy, a former NASA astronaut and space shuttle commander, penned an essay about Launch Complex 34 for the book. In the essay, she touches on one of the great tragedies of NASA's human spaceflight program: It was on that launchpad that the Apollo 1 capsule caught fire during a test exercise, killing all three men inside. Melroy mentions in the essay her work on the Columbia reconstruction team — the group tasked with sifting through the wreckage of the shuttle that was destroyed on its way back to Earth.

"[Complex 34] became a touchstone for her during that very, very difficult work," Miller said. "She came up with a beautiful essay regarding how that site affected her. And I think [her essay] is a tribute to all the fallen astronauts."

The book's title, "Abandoned in Place," is one that resonates with people who visit these old sites. Ray Bradbury wrote a poem about this phrase, and Miller chose to place it at the very beginning of the book. In the poem's final lines, Bradbury urged, "Old ghosts of rocketmen, arise. Fling up your ships, your souls, your flesh, your blood/Your blinding dreams/To fill, refill, and fill again/Tomorrow and tomorrow wand tomorrow's/Promised and re-promised/Skies."

The book is available for purchase through the University of New Mexico Press, and Amazon.com.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter