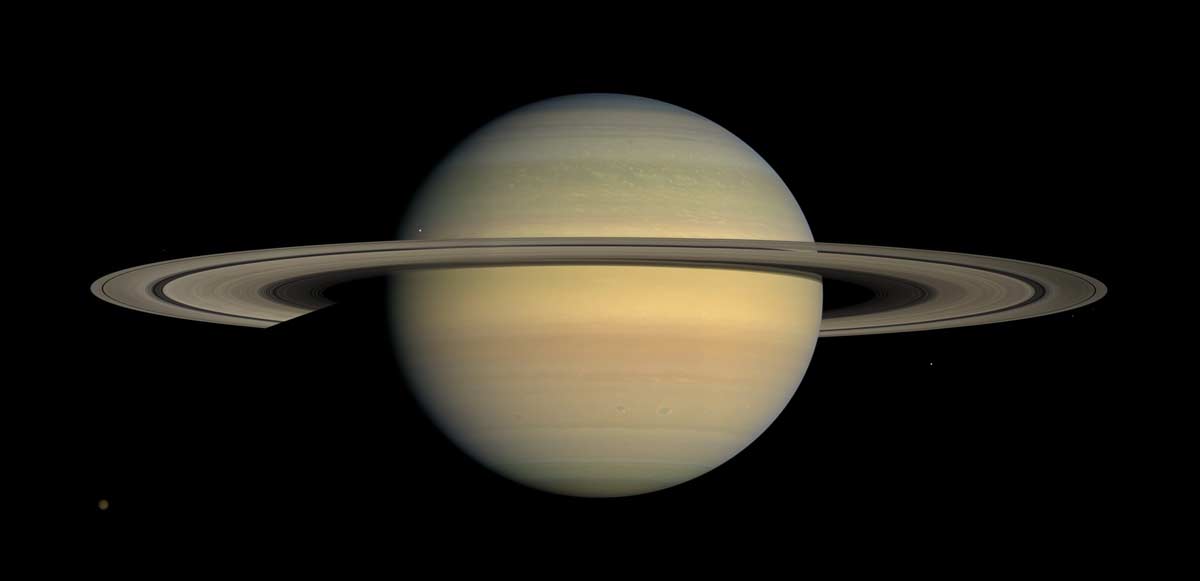

Interstellar Dust Found at Saturn

Some of the dust swirling around Saturn comes from beyond the solar system, a new study reveals.

NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft has sampled millions of dust grains since arriving at the ringed planet in 2004. While most of those grains come from jets erupting from Saturn's icy moon Enceladus, 36 of them were born between the stars, researchers said.

Cassini's find is not unprecedented; NASA's Jupiter-orbiting Galileo spacecraft and Ulysses, a sun-studying NASA/European Space Agency probe, both spotted dust that had interstellar origins. In both cases, the dust was believed to be a part of the local interstellar cloud, the zone of gas and dust through which our solar system is moving. [Saturn Photos: Latest Images from NASA's Cassini Orbiter]

"From that discovery, we always hoped we would be able to detect these interstellar interlopers at Saturn with Cassini. We knew that if we looked in the right direction, we should find them," study lead author Nicolas Altobelli, Cassini project scientist at the European Space Agency, said in a statement.

"Indeed, on average, we have captured a few of these dust grains per year, traveling at high speed and on a specific path quite different from that of the usual icy grains we collect around Saturn," he added.

Cassini's instruments have also allowed scientists to see what the dust is made of — something the Ulysses and Galileo missions were not able to do. The alien grains contain rock-forming elements such as magnesium, silicon, iron and calcium — all in abundances that meet the average for cosmic proportions, researchers said. Sulfur and carbon, however, were not as common as they are in "average" space dust.

Cassini's interstellar grains also varied little in composition, which surprised scientists. This uniformity makes them different from stardust grains found in some meteorites, which tend to be quite diverse.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Cosmic dust is produced when stars die, but with the vast range of types of stars in the universe, we naturally expected to encounter a huge range of dust types over the long period of our study," co-author Frank Postberg, of the University of Heidelberg in Germany, a co-investigator on Cassini's dust analyzer, said in the same statement.

It's possible that shock waves produced by supernova explosions could destroy cosmic dust, which might recondense several times, becoming more uniform over time, researchers said.Cassini will end its mission in September 2017 with an intentional death dive into Saturn, to avoid the chance of its crashing on a potentially life-friendly moon and thereby contaminating the surface. A similar procedure was followed for the Galileo mission at Jupiter, which concluded in 2003.

Dozens of spacecraft have traveled through the solar system, but only one — Voyager 1 – has reached interstellar space. Voyager 1 is still communicating with Earth as it travels outward.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.