Star's Wobble Could Reveal 'Earth-Like' Exoplanet

Starlight contains a lot of information.

By studying the electromagnetic spectrum of a star's light, you can see what elements it contains. You can also deduce its age, mass, stability and spin. As astronomical techniques and technologies have become more sophisticated, alien planets that would have otherwise remained invisible can also be detected via their gravitational tug on their host star.

ANALYSIS: Angry Little Stars Could Produce Life-Friendly Exoplanets

This mode of exoplanetary detection is known as the "radial velocity method" and it depends on the analysis of the periodic shift in the frequency of starlight to reveal the gravitational fingerprint of orbiting worlds. Basically, by watching a star's light for a long enough period, astronomers can see a star’s "wobble," a sure sign that a planet — or a system of planets — is in tow.

Now, a team of astronomers, led by Suman Satyal of the University of Texas at Arlington, has delved into the starlight of a nearby red dwarf star already known to possess two exoplanets, revealing there's the potential for a third exoplanet, possibly as small and as rocky as Earth, sandwiched between the orbits of the two known worlds.

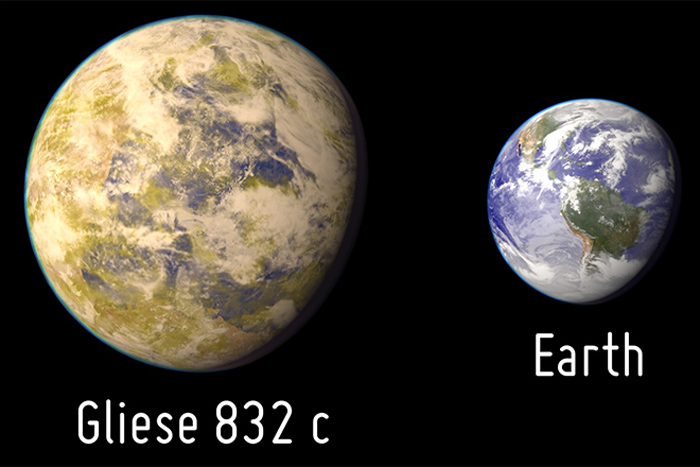

Gliese 832 is a well-known red dwarf. With a mass around half that of our sun, this diminutive star, located only 16 light-years away, has two exoplanets called Gliese 832b and Gliese 832c. Gliese 832b is the larger of the two and has the widest orbit, located 3.53 AU from its host star. It is also more massive, "weighing in" at around 60 percent the mass of Jupiter. Gliese 832c on the other hand is classified as a "super-Earth" of around five times more massive than Earth. It's orbit is extremely compact, coming within 0.16 AU of its star. As a comparison, in our solar system, the innermost planet Mercury comes no closer than 0.3 AU to the sun.

NEWS: Trickster Exoplanets May 'Fake' Life Signatures

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Gliese 832c hit the headlines in 2014, lauded as a possible "Earth 2.0." Though this is certainly a possibility, according to planetary scientists, it is more likely to be a hostile "Venus 2.0" with a thick, life-choking atmosphere.

Both 832b and 832c were detected by astronomers watching the star's light frequency slightly oscillate, an effect known as Doppler Shift. Much in the same way we hear a higher-pitch siren as a police car approaches compared to when the police car drives away, as a planet's gravity pulls a star toward us, its wavelength will become more compressed (increasing in frequency). As the planet orbits away, the star will also be pulled away, increasing the light's wavelength (decreasing the frequency). Through computer analysis of these oscillations, astronomers can "see" the orbits of planets around stars without actually seeing the planets themselves. Within these radial velocity measurements the companion planets' masses, orbital periods and orbital distances can be deduced by using established Keplerian laws of planetary motion.

Now, by revisiting the Gliese 832 star system, Satyal's team has taken a high-resolution look at the radial velocity data from the star and used computer modeling to see if another exoplanet "fits" between the orbits of 832b and 832c.

"We obtained several radial velocity curves for varying masses and distances for the middle planet," they write in a paper published by the arXiv pre-print service.

ANALYSIS: Seeking Earth-Like Alien Worlds in the 'Venus Zone'

Their analysis reveals that another exoplanet could indeed exist with an orbit between 0.25 to 2.0 AU from the star with a mass of 1 to 15 Earth masses. This range is pretty wide, but it provides an invaluable insight for future observations of the star system. An exoplanet within these orbital constraints would be in a stable orbit and would likely be another super-Earth, possibly a world occupying the star's habitable zone.

The habitable zone around any star is the region that is neither too hot or too cold, where water could exist in a liquid state on the planetary surface. As we all know, this is one of the key conditions for life (as we know it) to evolve, hence all the excitement whenever any world is discovered orbiting its star within the habitable zone.

It's worth remembering that Earth orbits the sun at 1 AU, pretty much in the middle of our star's habitable zone. Red dwarfs are much smaller and therefore cooler, so have far more compact habitable zones. Therefore, to maintain water in a liquid state on a hypothetical "Earth-like" planet orbiting a red dwarf, its orbit would have to be far closer. Red dwarfs have often been sited as key locations for alien life to thrive as, by their nature, they are long-lived and may allow complex life to evolve. But red dwarfs are known to be extremely active, often erupting with powerful flares that would irradiate any planet that orbits too close, requiring that planet to have a very well developed natural shielding in the form of a strong magnetosphere.

As you can see, it's one thing modeling the possible presence of a small rocky world around a nearby star, but it is quite another to find a true "Earth-like" planet that could support life as we know it. But it's important to try to at least pull any clues from a star's slight wobble to potentially help us track down alien worlds with any Earth-like quality.

Source: arXiv, h/t Physorg.com

Originally published on Discovery News.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.