NASA Cuts Funds for Mars Landing Technology Work

WASHINGTON — NASA is cutting funding for a Mars landing technology demonstration project by about 85 percent in response to budget reductions to its space technology program and the need to set aside funding within that program for a satellite servicing effort.

In a presentation to a joint meeting of the National Academies' Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board and Space Studies Board here April 26, James Reuter, NASA deputy associate administrator for space technology, said the Low Density Supersonic Decelerator (LDSD) project would get only a small fraction of its originally planned budget of $20 million for 2016.

That cut, he said, was required by the outcome of the fiscal year 2016 appropriations bill completed last December. NASA received $686.5 million for space technology, an increase of about $90 million from 2015. However, Congress moved the RESTORE-L satellite servicing from NASA's space operations budget account to space technology, and directed NASA spend $133 million, or nearly 20 percent of the overall space technology budget, on it. [NASA's Inflatable Flying Saucer for Mars Landings (Photo Gallery)]

"The net effect is that we had to find $40 million to cut" from other space technology programs, Reuter said. That ultimately included LDSD as well as a project to study composite structures for use on the Space Launch System's upper stage. Several smaller "game changing" technology programs were also cut, he said.

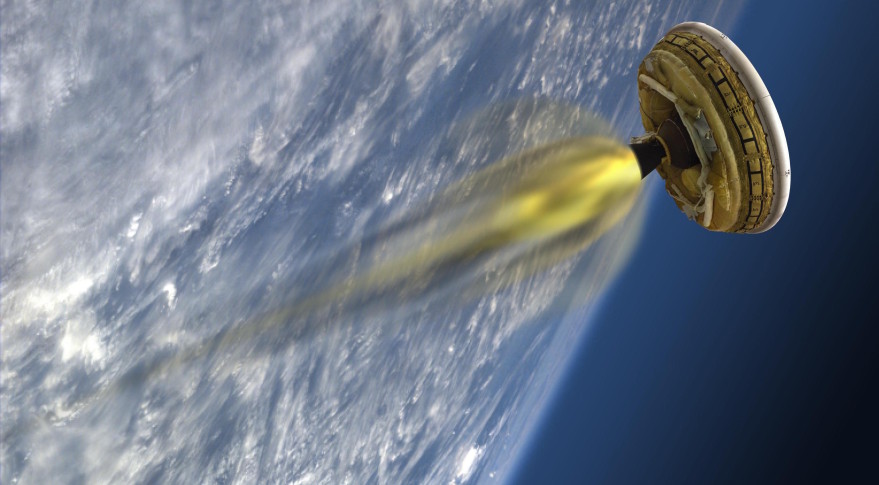

LDSD was studying the use of inflatable decelerators and advanced parachutes to slow down spacecraft as they enter a planetary atmosphere, particularly that of Mars. In two tests, a balloon carried the LDSD vehicle into the upper atmosphere, where the vehicle's rocket motor fired to accelerate it to Mach 3.5. LDSD deployed the inflatable decelerator, followed by the parachute, to slow down to subsonic speeds.

Two LDSD test flights, however, failed to successfully demonstrate the technology. In both flights the inflatable decelerator appeared to work as planned. However, in a June 2014 test, the parachute failed to fully open. During a second test a year later, the parachute opened, but suffered tears in its canopy.

NASA had not made a decision on whether to fund a third flight test of LDSD when it decided to cut funding the project, Reuter said after his presentation. The space technology program now plans to work with the science program on studies to better understand the dynamics of parachute deployment in those conditions.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Reuter said NASA likely would have carried out such studies regardless of the budget situation, but will be able to do less now. "We certainly would have been more aggressive" with that research at the original funding level of $20 million, versus the $3 million now available, he said.

In his talk, he warned that NASA's space technology program is facing another budget crunch in 2017. NASA requested $826.7 million for the program, but a spending bill approved by Senate appropriators April 21 provides $686.5 million, the same level as 2016. That bill also requires $130 million of that be spent on RESTORE-L, double the agency's request.

Other big programs, like a contract awarded April 19 to Aerojet Rocketdyne for solar electric propulsion work valued at $67 million, will further constrain NASA's space technology efforts if its budget remains at the Senate's level. "It will mean a bigger impact this coming year than what we just went through," Reuter said.

This story was provided by SpaceNews, dedicated to covering all aspects of the space industry.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeff Foust is a Senior Staff Writer at SpaceNews, a space industry news magazine and website, where he writes about space policy, commercial spaceflight and other aerospace industry topics. Jeff has a Ph.D. in planetary sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned a bachelor's degree in geophysics and planetary science from the California Institute of Technology. You can see Jeff's latest projects by following him on Twitter.