What Lunar Luck! Friday the 13th Is Prime Moon Viewing Time

When is the best time to look at the moon? Contrary to what you might think, it is not during the full moon. At that time, the sun is shining on the moon from straight overhead, making Earth's satellite look like the desert at high noon: flat and uninteresting.

The best viewing times are close to the quarter moons, when half the moon's surface is illuminated from Earth's perspective. This month, first quarter falls on Friday, May 13 (or Friday the 13th), and last quarter on Sunday, May 29. At those times, the sun is either rising or setting on the center of the moon, casting the lunar topography into sharp relief patterns of light and shadow. [Jupiter, Virgo Cluster and More in May 2016 Skywatching (Video)]

For most people, first quarter is easier to observe, because the moon is riding high in the early evening sky. The last-quarter moon is at its best at dawn, so is mainly appreciated by early risers.

Any night within four or five days of first quarter shows the moon's surface relief to best advantage. Those details are strongest along the line that divides light from shadow, called the lunar terminator.

With binoculars you can easily spot the moon's major surface features. Steadying your binoculars on a tripod will help with the view.

Early observers of the moon were not aware that it was an airless, desert world, and looked for features similar to those here on Earth. These viewers thought the vast lava plains that make up much of the moon's northern half were seas, and gave these areas fanciful names, using the Latin name "mare," pronounced "mah-ray," plural "maria," pronounced "mah-ray-ah."

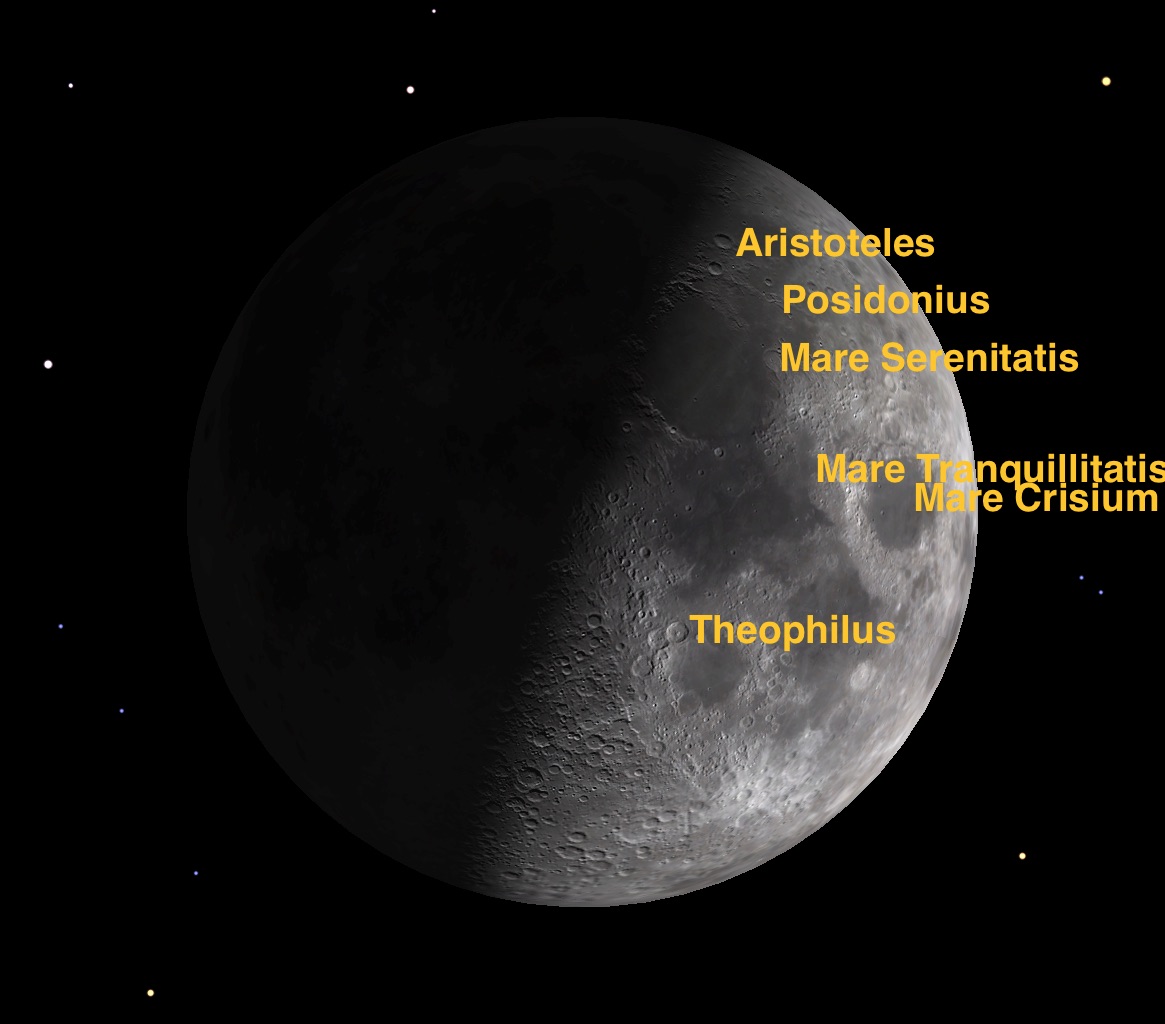

About halfway down the right side of the moon, as seen from Earth's Northern Hemisphere, is a small oval "sea" named the Mare Crisium, or Sea of Crises. Between the Mare Crisium and the terminator is a much larger, irregular "sea" called the Mare Tranquillitatis, or Sea of Tranquility. This is famous for being the landing place of Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969. Just north of the Mare Tranquillitatis is the Mare Serenitatis, or Sea of Serenity.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If you have access to even the smallest telescope, you will be able to see and identify hundreds of craters, which are small features caused by the impact of asteroids early in the moon's history. These have fresh, sharp outlines that deceptively suggest a recent formation, but in fact most were formed billions of years ago, long before there was any life on Earth. With no atmosphere to cause erosions, these scars remain as fresh as the day they formed.

The chart above shows some of my favorite craters. Theophilus is the northernmost of a triplet of craters, with its companions Cyrillus and Catharina to the south. On the northern "shore" of the Mare Serenitatis lies Posidonius, a large crater filled with lava, scarred from later impacts by smaller asteroids. Closer to the terminator is Aristoteles.

The craters on the moon are named after famous scientists and philosophers. This naming tradition has continued to the present day and includes scientists who were alive as recently as the 20th century. The only living persons with lunar craters named after them are the surviving Apollo astronauts.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of the moon during its quarter phase and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images in to spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.