Spinning Comets Can Tear Themselves Apart, Only to Be Reborn

Comets may often experience repeated cycles of destruction and reformation, spinning fast enough to break up but then reforming as their separate pieces slowly coalesce over time, a new study finds.

This finding could help explain the odd shapes of many comets imaged so far, researchers say.

Comets are clumps of ice and rock that generate long tails as their orbits bring them near the sun. The solid central part of a comet is known as its nucleus.

Previous research suggested that the nucleus of a comet can splinter apart; that research estimated that one comet splits every 100 years or so. To learn more about how comets break up, scientists analyzed data from the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, which reached Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014. [See Rosetta's Awesome Comet Photos]

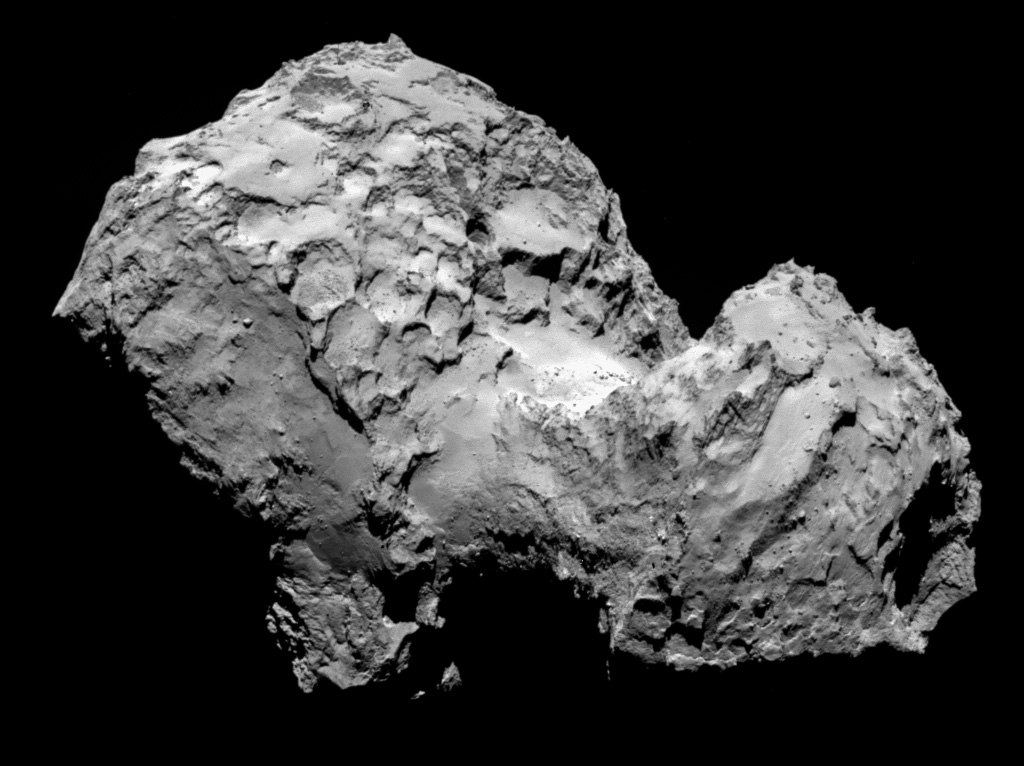

The 'rubber ducky' comet

Comet 67P is made up of two connected lobes. "It sort of looks like a rubber ducky, with a head and body," said study co-author Daniel Scheeres, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Prior work suggested that five of the seven comet nuclei that have been imaged in high resolution, including 67P and Halley's Comet, are two-lobed. This led the researchers to examine what might happen if these comets spun.

"When we were looking at 67P, we sort of knew intuitively that if it spun fast enough, the head and body should just separate from each other," Scheeres told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research team's computer models suggested that when sunlight converted 67P's ice directly into jets of gas in the past, the push that 67P received from these plumes caused its nucleus to spin. The strain that this whirling exerted on the nucleus may have caused it to fracture, which would explain the large cracks, several hundred feet long, currently seen in the nucleus, Scheeres said.

The scientists found that the chaotic nature of 67P's spinning has so far prevented its breakup. Still, they calculated that the comet's spinning should eventually increase to less than 7 hours per rotation — fast enough for the head to pop off, Scheeres said.

However, when this fragmentation occurs, the separate pieces will be unable to escape one another. Instead, the pieces of 67P should orbit one another for a while, until they ultimately merge slowly to form a new two-lobed configuration. This pattern could go on for the life of the comet, Scheeres said.

Comet destruction and rebirth

The researchers also examined four other comets with two-lobed nuclei. They found that the nuclei's structures were consistent with similar cycles of destruction and reformation, suggesting that such behavior is common to comets that often come near the sun.

"These comets aren't dead, frozen chunks of ice," Scheeres said. "They can actually change over time — they can split and come back together in new configurations, and they may have done that several times already over the courses of their lifetimes."

Previous research found that comets were not major players in the so-called Late Heavy Bombardment, a giant barrage of rocks that struck Earth and the rest of the inner solar system about 4 billion years ago. The scientists noted that the cycles of destruction and reformation that comets undergo might help explain why comets were not a big part of this shooting gallery — many comets would have been destroyed as they wandered toward the sun.

Future research will analyze more comets "to learn more about their shapes and spin evolution," Scheeres said. "We want to see if we can better understand how this new evolutionary process we've identified can change comets over time, and help us explain unknown phenomena linked to comets, like how they can brighten very dramatically at random times in their orbits, or disappear from view," he added. "We think these sorts of phenomena may be linked to how they can spin fast enough to break apart."

The scientists detailed their findings in the June 2 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us