From King Tut to Kitchen Knives, Meteorite-Made Relics Span Centuries

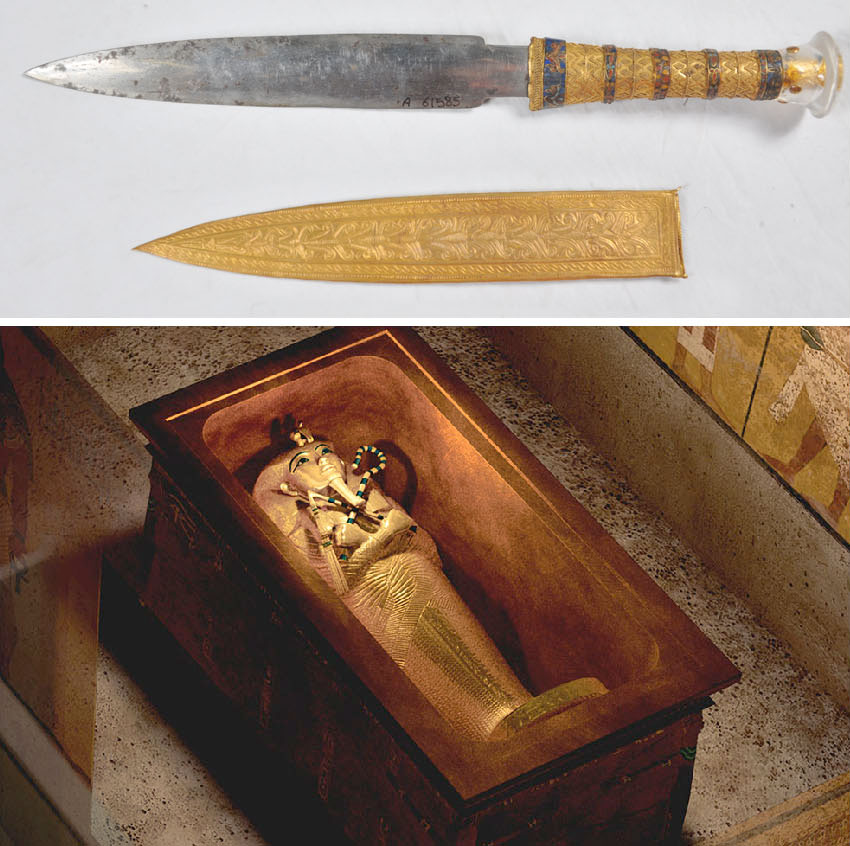

The discovery that King Tut was buried with a dagger made out of a meteorite has drawn news headlines worldwide and captured the imagination of the public. As unusual as it may seem, though, the pharaoh's blade is not the only ancient or odd artifact that was forged from space-based metal.

Although certainly still rare, a number of other antiquities found over the years were comprised of iron derived from meteorites. And even today, master artists are fabricating new examples of meteorite-made tools and decorative ornaments.

The blade interred with Tutankhamun, now on display in Cairo, Egypt, is only the latest Egyptian relic to be traced back to a meteoritic origin. [King Tut Wielded A Blade 'Not of This Earth' (Video)]

As far back as 1911, researchers found that beads excavated from another Egyptian tomb were found made from iron meteorites. The nine small beads, unearthed from a cemetery along the west bank of the Nile tomb in Gerzeh, were dated to 3200 B.C. They were fabricated by hammering the "heaven-sent" material into thin sheets.

According to researchers, ancient Egyptians considered the meteoritic iron to be of great value, possibly considering the falling rocks as a message from the gods. They called the meteorites "iron from the sky."

The Egyptians, however, were not the only ones to place importance on the fallen rocks.

A Tibetan Buddha statue, possibly dating back to the 8th to 10th centuries A.D., was carved from an ataxite, a rare class of meteorite that contains high levels of nickel.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sculpture, which depicts a figure perched with his legs tucked in and a Buddhist swastika on his chest, was reportedly found and brought to Germany in 1938-1939. This was done as part of a Nazi-funded expedition to discover the roots of what Nazis called the Aryan race. Ownership of the statue was later passed to a private individual.

Known as the "Iron Man," the statue is about 9.5 inches (24 centimeters) tall and weighs about 23 lbs. (10.6 kilograms). Since the statue made headlines in 2012, though, some researchers have called its provenance into doubt, suggesting the Buddha could be a European counterfeit made during the 20th century. The statue's meteoritic origin is not in question, however.

The ancient origins of two Chinese bronze weapons with meteoritic iron blades are not in doubt. The artifacts were the focus of a Smithsonian Institution study published by the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. [Space-y Tales: The 5 Strangest Meteorites]

"Though they have rarely been exhibited ... one is a broad axe (ch'i) with a bronze tang (nei) and the rusted remains of an iron blade; the other is a dagger axe (ko) with a bronze blade and the remains of an iron point," wrote Rutherford Gettens, Roy Clarke and W.T. Chase in the 1971 paper. "These two weapons are of high interest to the historian of technology for three reasons, [including] evidence that the iron in both weapons is of meteoritic origin."

Dated to about 1000 B.C., both weapons may have been functional but most likely were not used in battle, experts say.

"It might be presumed that the [meteoritic] iron blades were attached to the weapons to make them more functional, but because of the scarcity of iron in the early Chou period, and the decor on the weapons, especially the inlay on the ch'i, it seems they were probably made for ceremonial purposes," the researchers wrote.

The Freer Gallery also has another meteoritic blade that was created 400 years ago for the leader of the Mughal Empire in India.

"At dawn, a tremendous noise arose in the east. It was so terrifying that it nearly frightened the inhabitants out of their skins," wrote Indian Emperor Jahangir about a meteor that lit up the skies within his kingdom in April 1621. "Then, in the midst of tumultuous noise, something bright fell to the earth from above."

"His fascination with unusual natural events — and his power to harness their aura — is revealed by this dagger's blade, forged from the glittering meteorite," Freer curators wrote in their description of the 10.25-inch-long (26.1 cm) dagger. "Jahangir further noted that the blade 'cut beautifully, as well as the very best swords.'" (This description also includes the above quote by the emperor.)

The use of meteoritic iron in weapons and ceremonial tools did not end in ancient times.

For example, master Japanese swordsmith Yoshindo Yoshiwara recently forged a katana, named "Tentetsutou," from fragments of the prehistoric Gibeon meteorite. Similarly, California-based blacksmith Tony Swatton produced a replica of Sokka's sword from the animated series "Avatar: the Last Airbender" using fragments of the Campo del Cielo meteorite found in Argentina.

Of a more utilitarian — but no less impressive — use, master bladesmith Bob Kramer, based in Olympia, Washington, has crafted steel chef's knives forged from meteoritic iron.

"I am incorporating meteorites into my material," Kramer said in a 2015 interview with chef Anthony Bourdain for "Raw Craft," a short-film series produced by The Balvenie whisky distillery. "This is probably man's first encounter with a solid chunk of iron — that's a meteorite, that's a star stone."

Robert Pearlman is a Space.com contributing writer and the editor of collectSPACE.com, a partner site and the leading space history news publication. Follow collectSPACE on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.