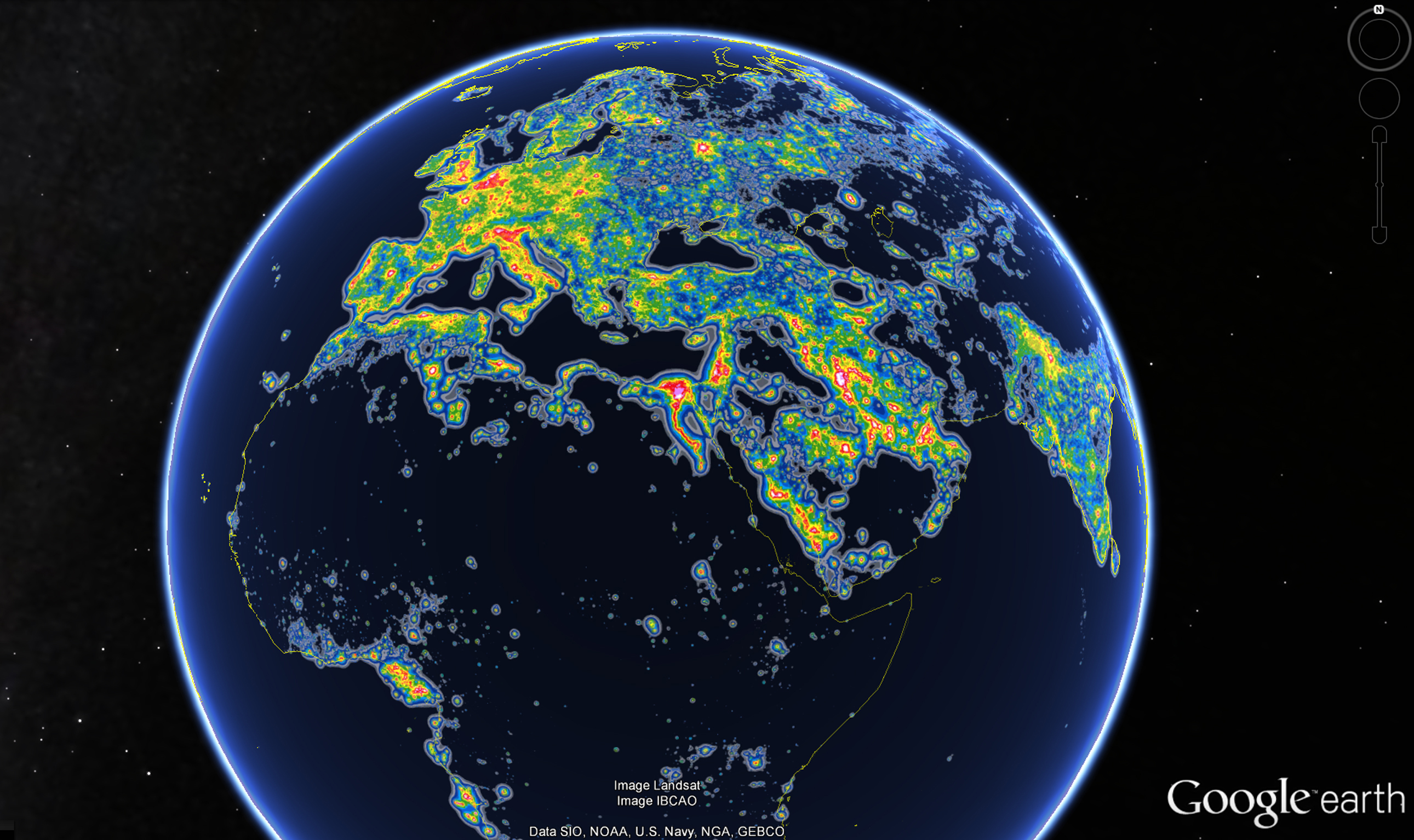

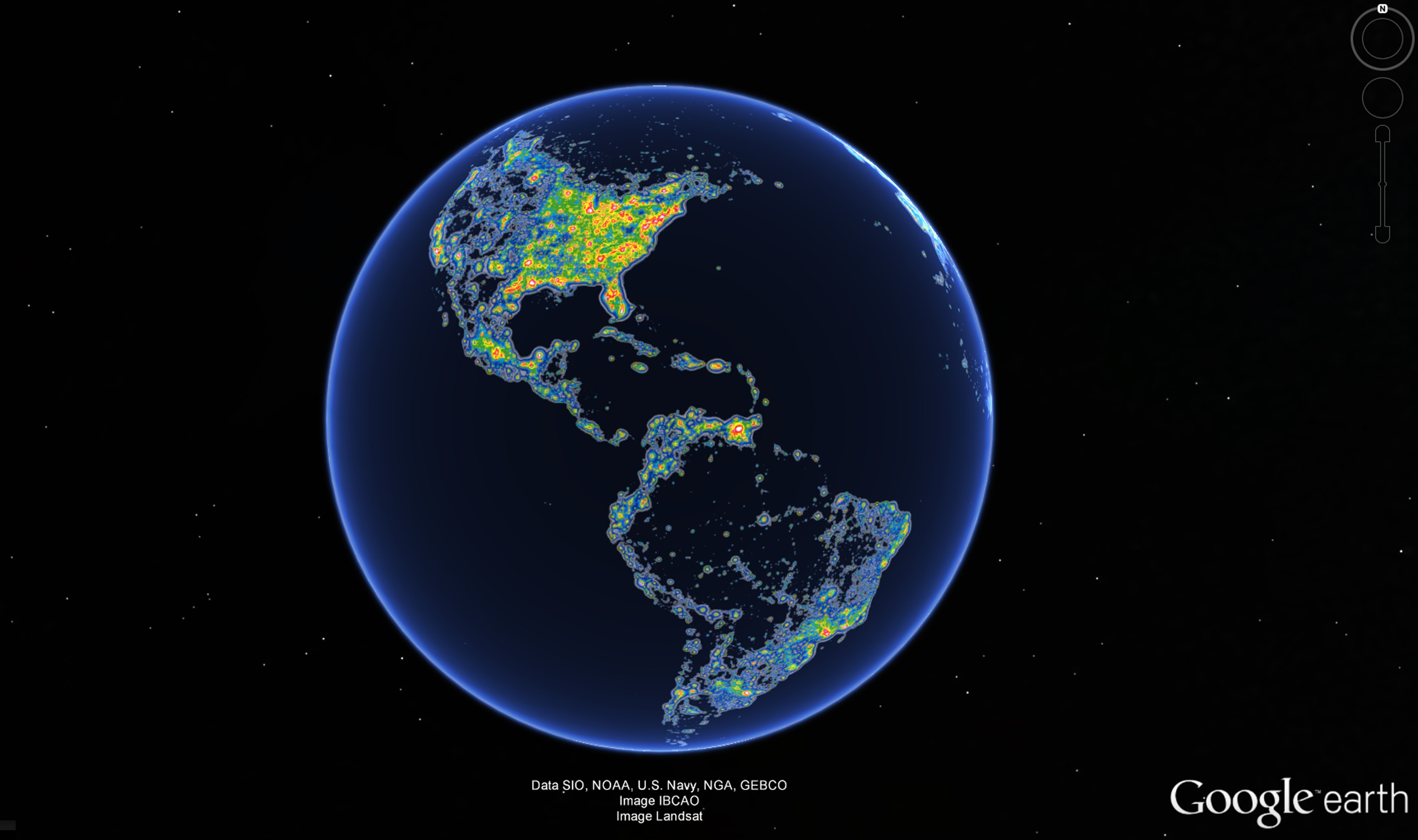

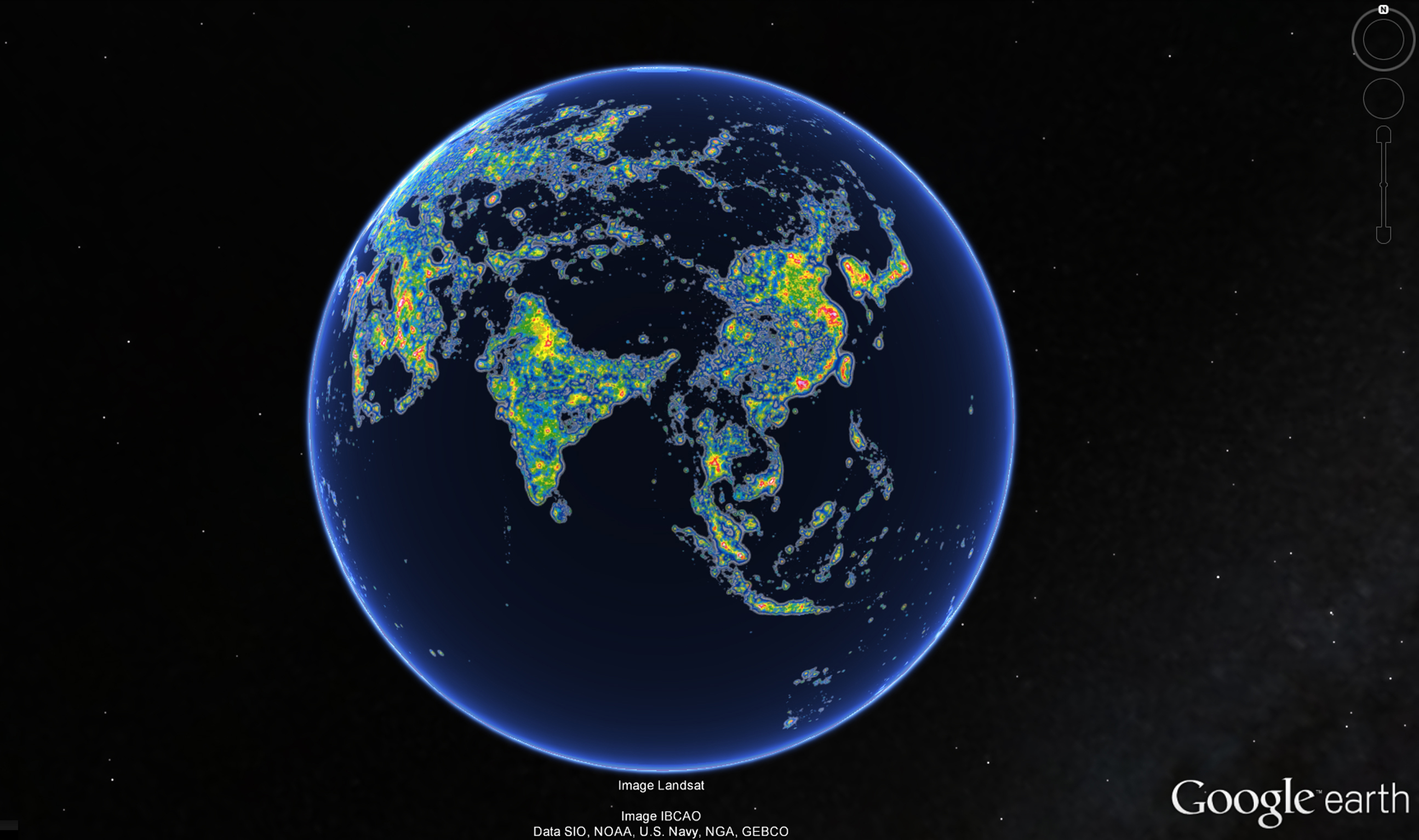

Light Pollution Ruins Night-Sky Views for One-Third of Humanity

A new, comprehensive atlas of worldwide light pollution reveals that one-third of all people cannot see the Milky Way in the sky, including nearly 80 percent of North Americans.

The atlas, painstakingly produced over the course of more than 10 years from satellite data and verified by more than 30,000 on-the-ground measurements, was published today (June 10) in the journal Science Advances. The work describes the effect of the rapid increase in artificial light on the night sky throughout the world, documenting this lesser-known form of pollution that can affect local ecosystems, damage human health and incur large, unnecessary energy costs. The project also offers suggestions for how to reduce light pollution's impact. The researchers also created this video to visualize the extent of light pollution on Earth.

"Of course, there is a connection between the development of a country and the pollution," study lead author Fabio Falchi, of the Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute in Italy (known by its Italian acronym ISTIL), told Space.com. "But this is not a law of nature. The paper suggested [how] to light in a way that pollutes the environment much less." [Photos: Light Pollution Around the World]

"It's a monumental piece of work," Richard Wainscoat, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii, told Space.com. "I think everybody was waiting for many, many years to see this."

Wainscoat, who was not involved in the new study, is a past president of the International Astronomical Union's Commission 50, which works to preserve important dark-sky sites around the world.

Falchi and his collaborators put together the atlas using data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite, the Earth-watching spacecraft whose observations created the famous "Blue Marble" views of Earthin 2012.

Suomi NPP, a spacecraft about the size of a minivan, orbits 512 miles (824 kilometers) above Earth to monitor changes in the planet's climate and help with weather forecasting. Study team members ran that data, and observations from the ground, through light-pollution-propagation software to create a set of maps that determine the light pollution experienced at any given location.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The atlas also allows researchers to pinpoint which places are particularly far from pristine, dark skies. Cairo was the most distant from any region with a view of the Milky Way, Falchi said. Other areas particularly far were the Belgium/Netherlands/Germany transnational region, the Padana plain in northern Italy and the sequence of cities from Boston to Washington, D.C., in the northeastern United States. In some locations including Singapore, inhabitants never experience full night — in fact, the researchers said in press materials, skies are so bright over most of that population that their eyes never fully adapt to night vision.

Several important astronomy sites are still dark at night, including locations in north Chile, Hawaii's Big Island, La Palma in the Canary Islands, Namibia and the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico, Falchi said. Much of Africa, and deserts around the world where the population is low, also offer good skywatching opportunities, he added. However, in many of those places, you can still spot light pollution on the horizon from neighboring areas.

The researchers have prepared an interactive online map hosted by the University of Colorado, Boulder, and Falchi will soon release a printed book through Amazon and CreateSpace called "The World Atlas of Light Pollution" to further document the new research.

Light's impact

"There's increasing research that shows that exposure to artificial light at night is bad for us physically — [it] confuses our circadian rhythms and contributes to sleep disorders and impedes the production of melatonin," said Paul Bogard, author of the recent book on light pollution "The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light" (Little, Brown and Company, 2013).

"Environmentally, there haven't been a ton of studies, but what we do know are things like the effect on sea turtles, migrating birds, moths, bats," Bogard, who was not part of the new study, told Space.com. "The statistics I always use are, 60 percent of invertebrates are nocturnal, and 30 percent of vertebrate species are nocturnal, so they're relying on darkness to live."

Both Bogard and Wainscoat also brought up the less tangible consequences of a generation unaccustomed to seeing the full splendor of the night sky.

The atlas is "a wake-up call to society," Wainscoat said. "Also a little bit of a wake-up call to astronomers. People need to be able to look up at the sky and be able to imagine and try to understand their place in the universe. If they can't see any stars and they can't see the Milky Way anymore, they're no longer perhaps interested in where we are, in our place in the universe."

(In 1976, Wainscoat drove about 10 miles, or 16 km, outside Perth, Western Australia to see Comet West streak by, an event that he said helped inspire his work as an astronomer. Today, he said, one might have to drive as far as 200 miles, or 320 km, out of that city to see a similar comet.) [Photos: Light Pollution Shines in 'The City Dark']

Wainscoat emphasized that the increase in light pollution is gradual, about 5 or 10 percent per year. So it's tough to spot the brightening as it's happening, but the effect over 10 or 20 years is dramatic, he said.

"The disturbing part is, it doesn't have to be like this," Wainscoat said. "There's a tremendous amount of irresponsible lighting throughout the world. It's all based on money and profit, and it's not based on what's right for the environment."

Next steps

To restore Earth's dark sky — an effort that's already underway in certain natural preserves and other regions — it's not necessary to just cut out nighttime light altogether. Instead, the researchers wrote, systems must prevent light from shining upward, use the minimum light needed for any given task (and turn off lights when not needed, as when illuminating a deserted area) and avoid the increasingly common blue-tinged LED lights. These interfere more with human circadian rhythms and scatter more broadly than yellow light by reflecting off air molecules.

Bogard described similar methods in his book.

"Nobody's saying, 'Let's not have light at night.' That's not the point," he said. "The point is that we're using way more than we need to use, and we're using it in ways that are harmful to us and harmful to the environment, and waste money, and actually in many cases make us less safe than we would otherwise be." (For instance, bright lights at night can obscure vision and create disorienting shadows.) [Utah Stargazing: Bryce Canyon Astronomy Festival Travelogue]

"We think if some light is good, more light is better, and that's not true," Bogard added.

To expand upon the atlas, Wainscoat said, he would like to see multicolor data from a higher resolution satellite that can send down more detail and more accurately detect blue-tinged light (which Suomi NPP is not sensitive to). Unlike images from the International Space Station, which show smaller patches of Earth in stunning detail, views from most available survey satellites, including Suomi NPP, are hazier once you get down to small features. A dedicated setup could also return information about changes in light pollution over time.

Falchi, too, would like to expand the work to follow how light pollution changes and develops. "At ISTIL, we are working for free in our free time, so research cannot be fast," Falchi said. "If some generous magnate will find our research worth funding, we may expand and work full time on this. We would like to study the variation of light pollution with time and to make maps of the whole night-sky hemisphere for each site."

For now, though, the atlas provides the first complete look at light pollution's extent on a global scale, the researchers said in the paper. The atlas can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of light-reduction programs and identify the places that are most in need of protective measures. And it acts as an important reminder about the extent of the problem, the researchers said.

"It's way too easy, with light pollution, to imagine that things aren't so bad," Bogard said. "It still gets dark at night, [or] in the city it's bright, but if you get out into the country, it's still dark. And I think what Fabio's map shows is that neither of those things is true.

"Most of the kids that are born in the states and in Europe have no idea what they're missing, and they'll never have that experience of being overwhelmed and inspired," he added. "That's hard to put a price tag on, but it's still a big problem."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.