When Will China's 'Heavenly Palace' Space Lab Fall Back to Earth?

A Chinese space lab is bound to come back to Earth relatively soon, but when and where this happens is a matter of debate and speculation.

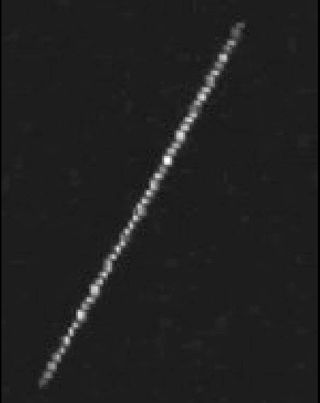

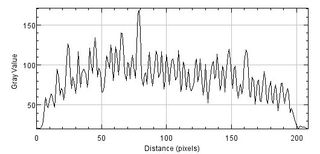

For example, some satellite trackers think China may have lost control of the uncrewed 8-ton (7.3 metric tons) vehicle, which is called Tiangong-1. That's the view of Thomas Dorman, who has been documenting flyovers of the spacecraft using telescopes, binoculars, video and still cameras, a DVD recorder, a computer and other gear.

"If I am right, China will wait until the last minute to let the world know it has a problem with their space station," Dorman told Space.com. [See photos of China's Tiangong-1 space lab]

"It could be a real bad day if pieces of this came down in a populated area … but odds are, it will land in the ocean or in an unpopulated area," added Dorman, an amateur satellite tracker who has been keeping tabs on Tiangong-1 from El Paso, Texas since the space lab's September 2011 launch. "But remember — sometimes, the odds just do not work out, so this may bear watching."

However, Chinese officials have yet to confirm the end-of-life plans for Tiangong-1, and some experts think it may still be possible to bring the spacecraft down in a controlled fashion. (You can find out when to look for Tiangong-1 in your night sky with our Satellite Tracker Map, powered by N2YO.)

Space station stepping stone

Tiangong-1 — whose name means "Heavenly Palace" — served as a stepping-stone toward a larger space complex that China wants to be operational in Earth orbit around 2020.

Tiangong-1 was used to perform docking exercises during a series of missions — the uncrewed Shenzhou-8 mission in 2011 and the crewed Shenzhou-9 and Shenzhou-10 flights in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shenzhou-10's return to Earth in June 2013 marked the end of Tiangong-1's docking duties. The Heavenly Palace then entered an in-orbit "operation management phase," undergoing changes in its flying mode, orbit-maintenance maneuvers and other activities.

Earth observation, and end of the line

According to the China Manned Space Engineering (CMSE) office, Tiangong-1 is also outfitted with payloads such as Earth observation instrumentation and space environment detectors.

"Tiangong-1 has obtained a great deal of application and science data, which is valuable in mineral resources investigation, ocean and forest application, hydrologic and ecological environment monitoring, land use, urban thermal environment monitoring and emergency disaster control. Remarkable application benefits have been achieved," CMSE officials wrote in a 2014 statement.

For example, Tiangong-1 provided timely data across a broad range of the electromagnetic spectrum during China's Yuyao flood disaster in 2013, and collected imagery of a devastating Australian forest fire as well, CMSE officials have said.

Earlier this year, however, state-run news agencies in China reported that the CMSE had terminated Tiangong-1's data-gathering activities. Furthermore, CMSE officials explained that the telemetry link to the space lab had failed, seemingly dooming the vehicle to an uncontrolled fiery fall in the future.

Dorman said his observations support this looming scenario. And it makes sense to Dean Cheng, a senior research fellow at the Asian Studies Center at the Heritage Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based conservative think tank. [6 Biggest Spacecraft to Fall Uncontrolled From Space]

Cheng said he's surprised that Chinese space authorities have not declared exactly when Tiangong-1 will come back to Earth, even though its operational life seems to be over.

"That would seem to suggest that it's not being deorbited under control," Cheng told Space.com. "That's the implication."

Whatever the true status of the space lab, Cheng said, there are some interesting implications.

"When you deorbit somewhat larger items, you would have a 'best practices' policy of making a controlled re-entry," Cheng said. "In fact, this will be an interesting test of whether or not China is going to be more open about its space program writ large."

Cheng said that providing the world with an idea of when and where 8 tons of space hardware will fall back to Earth "would be consistent with a more open space policy … and frankly would be an act of responsible behavior."

Other possibilities

Such speculation does not mean that Tiangong-1 is definitely out of control, other experts cautioned.

"It seems it may be much ado about nothing," said T.S. Kelso, a senior research astrodynamicist at the Center for Space Standards & Innovation (CSSI), a research arm of Analytical Graphics.

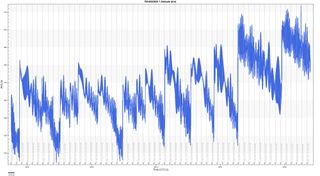

Kelso has plotted the altitude history of Tiangong-1 from just after its launch to more recent times. He told Space.com that the Chinese space lab's orbit was reboosted relatively recently, in mid-December 2015.

"That reboost put it higher than it had been anytime prior to that in its mission," Kelso said.

Kelso said he does not have "any direct way to measure" Tiangong-1's stability. "But we might expect to see the rate of decrease in altitude — the slope between reboosts— increase if it was tumbling, since the station would have higher drag," he added. "Instead, we see the slowest decrease in altitude in recent years — consistent with the lower drag at a higher altitude."

Kelso said his reading of the data suggests that Tiangong-1 is dormant but stable.

"So that might be why the Chinese aren't responding … they probably don't understand why they would need to," Kelso said. "I guess I would want to see some very specific data, notionally covering a period where Tiangong-1 was supposed to be stable, to show that it is now uncontrolled, before reading too much more into this."

Based on the latest tracking information, if there are no further reboosts of the Chinese craft, "we would expect to see Tiangong-1 re-enter just around the end of 2017," Kelso said.

If China does indeed have control over the space lab, why keep it in orbit rather than nudging it back to Earth immediately?

"The suggestion has been made," Dorman said, that "the reason China hasn't done a re-entry of Tiangong-1 is, the space station is low on fuel, and China is waiting on a natural decay to a much lower orbit before they can do a burn to bring the station down."

Next moves

Meanwhile, China plans to launch the Heavenly Palace's successor, Tiangong-2, this September. A month later, the crewed Shenzhou-11 mission is scheduled to dock with Tiangong-2.

In 2017, the maiden flight of China's robotic cargo ship, Tianzhou-1, will dock with Tiangong-2. This supply ship is to be boosted by the Long March 7, a new Chinese rocket slated to debut this year.

China's state-run Xinhua news outlet has reported that the core module of the nation's 60-ton, medium-size space station — due for launch around 2018 — will be named "Tianhe-1," a Chinese word for "Milky Way" or "galaxy."

Wang Zhongyang, of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp., said two space labs will be launched later and dock with Tianhe-1, according to Xinhua. Wang added that construction of the space station "is expected to finish in 2022," Xinhua reported.

Wang pointed out that China also intends to launch a space telescope akin to NASA's iconic Hubble Space Telescope soon after the space station is operational. This telescope will "be in a separate space unit and share orbit alongside the space station," Xinhua reported.

Leonard David is author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," to be published by National Geographic this October. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel six-part series coming in November. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.