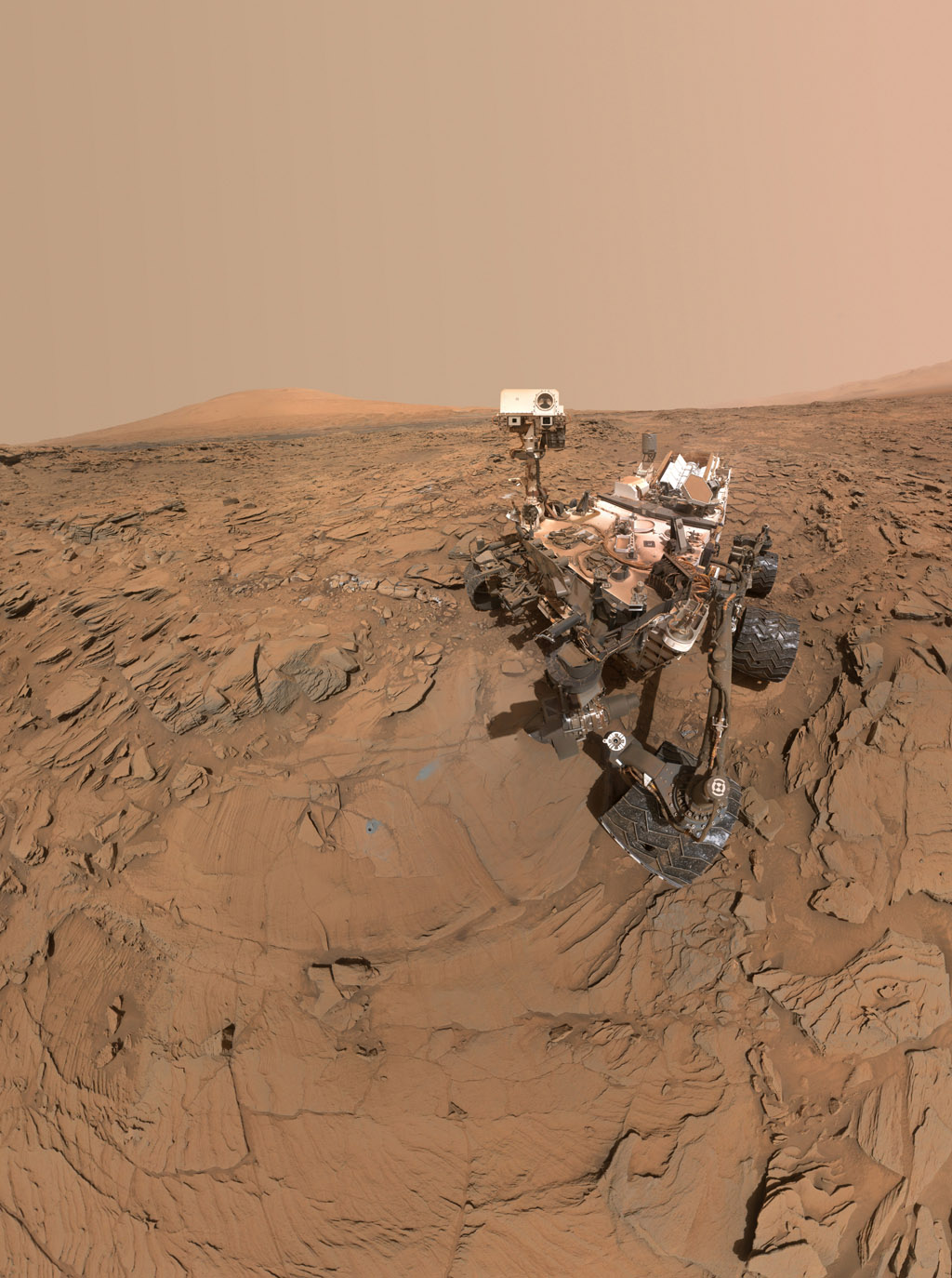

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has captured two more otherworldly selfies.

The 1-ton robot's latest self-portraits were snapped May 11 in the foothills of the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp, at a site dubbed Okoruso. Curiosity had stopped there to drill into the mudstone bedrock and collect samples for analysis, NASA officials said.

The Okoruso drill hole, surrounded by gray powder, is clearly visible in front of the rover in both images. Another hole from a previous drilling operation is also visible to the left of Curiosity's "head" in the photos, though you may have to squint a bit to spot it. [The Top 10 Space Robot Selfies]

Both self-portraits are mosaics of images taken by the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), a camera at the end of Curiosity's 7-foot-long (2.1 meters) robotic arm. (If you're curious about exactly how Curiosity takes selfies, watch this NASA explainer video.)

In one of the newly released mosaics, Curiosity's head is pointing toward the camera, whereas the robot's head is facing away in the other. NASA combined the two photos into a GIF that makes it appear as if Curiosity is turning its attention to the towering Mount Sharp, which rises into the Martian sky in the background.

That impression is appropriate, because Curiosity is indeed set to climb higher up Mount Sharp (though not nearly to the top).

The mountain has been the rover's main science destination since before Curiosity's August 2012 landing. The rover spent nearly a year exploring the area near its touchdown site, finding, among other things, that the region was capable of supporting microbial life long ago, and then departed for Mount Sharp's base in July 2013.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The rover reached the mountain's foothills in September 2014 and has been ascending slowly ever since. Along the way, the robot has been studying the rocks as it goes for clues about how Mars shifted from a relatively warm and wet world billions of years ago to the cold, dry planet it is today.

From November through May, Curiosity didn't gain much altitude; the car-size robot explored sand dunes, crossed a feature called the Naukluft Plateau, and spent a fair bit of time drilling rocks and analyzing samples.

This latter work, which investigated rock formations known as Murray and Stimson, has revealed new insights about the history of liquid water in the area, mission team members said.

"The big-picture story is that this may be one of the youngest fluid events we're likely to study with Curiosity," Albert Yen, a Curiosity science team member from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "You had to lay down the Murray, then cement it, then lay down the Stimson and cement that, then fracture the Stimson, then have fluids moving through the fractures."

Curiosity's climb resumed in earnest last month, mission team members said, so some selfies with even grander vistas may be in the offing.

"Now that we've skirted our way around the dunes and crossed the plateau, we've turned south to climb the mountain head-on," Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, also of JPL, said in the same statement. "Since landing, we've been aiming for this gap in the terrain and this left turn. It's a great moment for the mission."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.