Rare Newborn Planet May Be the Youngest Ever Detected

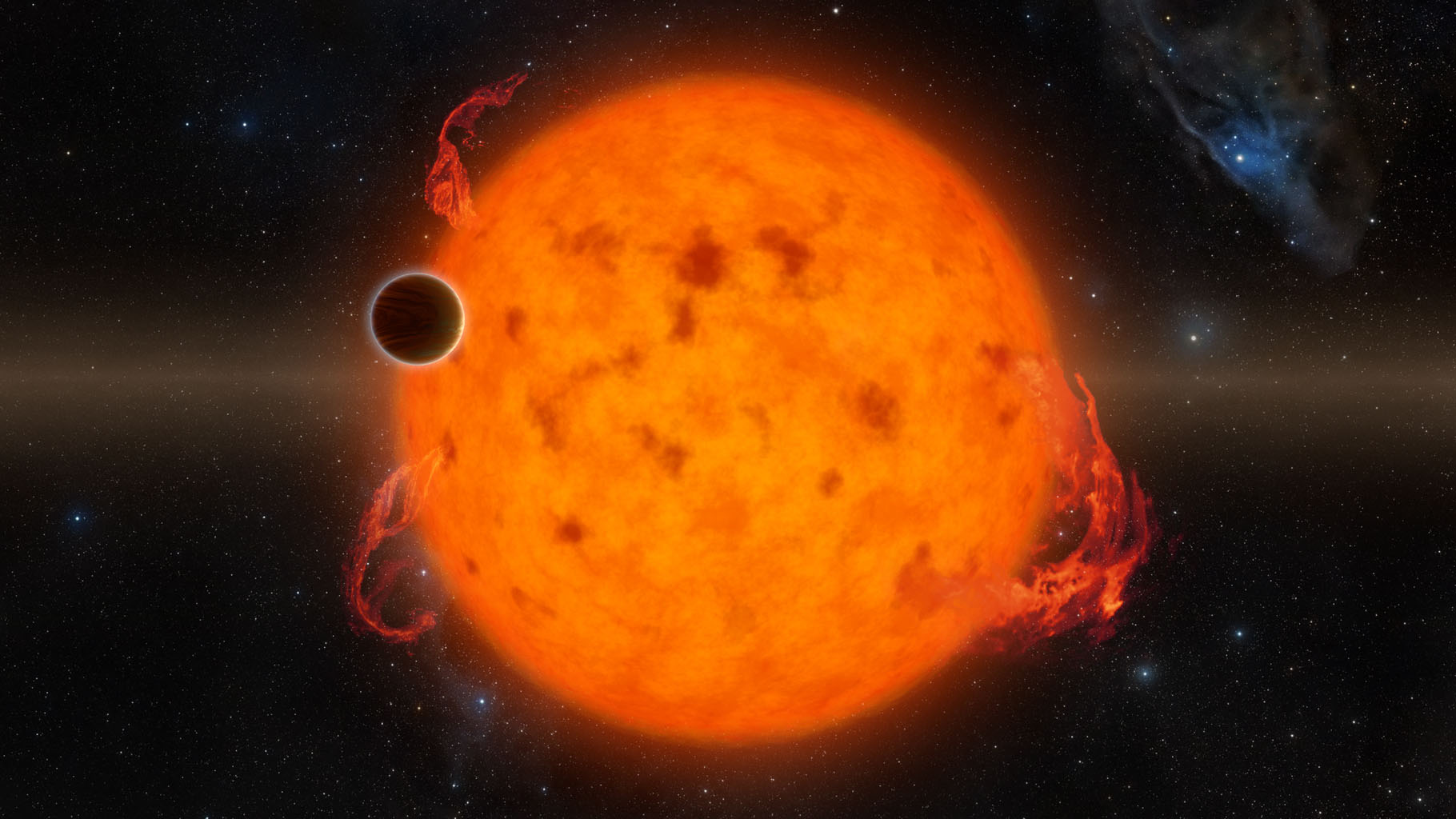

A distant, Neptune-size planet 500 light-years from Earth appears to be the youngest fully formed exoplanet ever found crossing its star, raising questions about how it formed so close, so quickly.

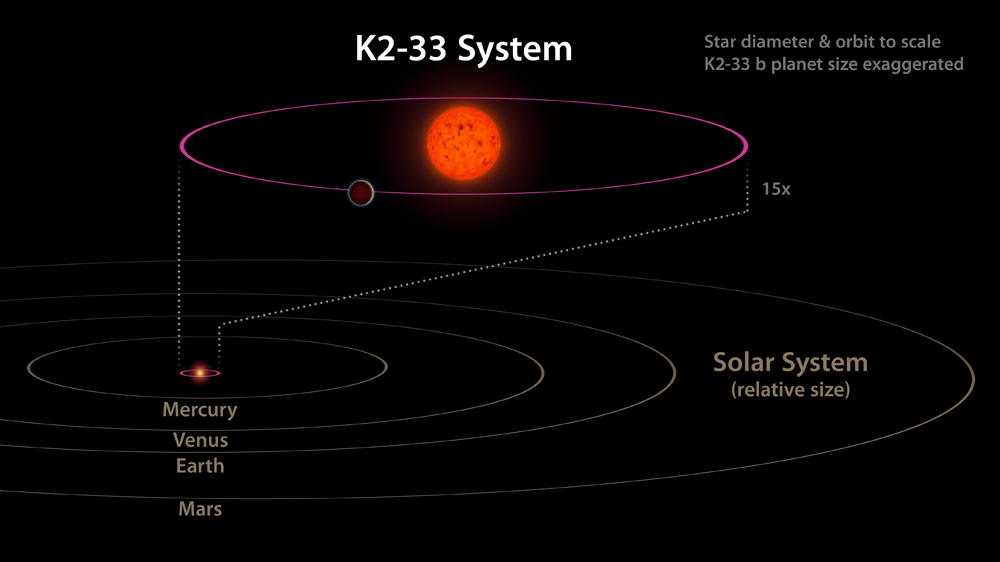

Researchers first found the planet, which whisks around its star every five days, using the Kepler space telescope currently orbiting the sun alongside Earth. Its star is only 5 million to 10 million years old, suggesting that the planet is a similar age — incredibly young, on a cosmic scale. Researchers said it was the youngest planet spotted fully formed around a distant star, and it is nearly 10 times closer to its star than Mercury is to the sun.

"Our Earth is roughly 4.5 billion years old," Trevor David, a graduate student researcher at the California Institute of Technology and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "By comparison, the planet K2-33b is very young. You might think of it as an infant." (This Space.com video explains the young exoplanet find.)

Most of the more than 3,000 confirmed planets around other stars orbit stars more than 1 billion years old, NASA Jet Propulsion Lab officials said in the statement — so this young star and planet pair offers a rare opportunity to see earlier stages of planet development.

Kepler detected the planet during its K2 mission by catching the star dimming and brightening periodically as the planet passed in front of it — a detection process known as the transit method. Researchers used data from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, also in an Earth-trailing orbit, to verify that the darkening was caused by the planet and to see that the star is surrounded by a thin layer of debris.

That layer is likely the remnant of a thick disk of debris that encircled the star when it first formed — the raw material from which planetary systems form. In this case, the thin disk suggests the star is near the end of its planet-forming days, the researchers said in the study, released today (June 20) in the journal Nature.

"Initially, this material may obscure any forming planets, but after a few million years, the dust starts to dissipate," Ann Marie Cody, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said in the statement. "It is during this time window that we can begin to detect the signatures of youthful planets in K2."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Combined with its youth, the planet's close proximity to its star is a puzzling feature of the newly found system, the researchers said. Some astronomical theories suggest that a planet of its mass would have to form farther out and slowly migrate inward over hundreds of millions of years, but the star is too young for a process that long to have occurred, the researchers said in the statement.

Instead, it must have either migrated much more quickly, in a process called disk migration powered by the orbiting disk of gas and debris, or formed right at the spot that researchers see it in now.

"After the first discoveries of massive exoplanets on close orbits about 20 years ago, it was immediately suggested that they could absolutely not have formed there," David said. "But in the past several years, some momentum has grown for in situ formation theories [that the planet could form right where it is], so the idea is not as wild as it once seemed."

"The question we are answering is, did those planets take a long time to get into those hot orbits, or could they have been there from a very early stage? We are saying, at least in this one case, that they can indeed be there at a very early stage," he added.

The planet K2-33b is one of two newborn-planet announcements published in today's issue of Nature. The other newborn planet, which orbits a 2-million-year-old star called V830 Tau located 430 light-years away, appears to be a giant planet near the size of Jupiter sitting in an orbit one-twentieth the distance from Earth to the sun. The researchers identified the planet by watching its star wobble back and forth periodically as the massive planet orbited. If that planet formed farther outward and migrated closer, it would have had to rush in at a very early stage of its formation.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to clarify the Kepler and Spitzer telescopes' orbits around the sun.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.