Pluto May Harbor a Liquid Ocean

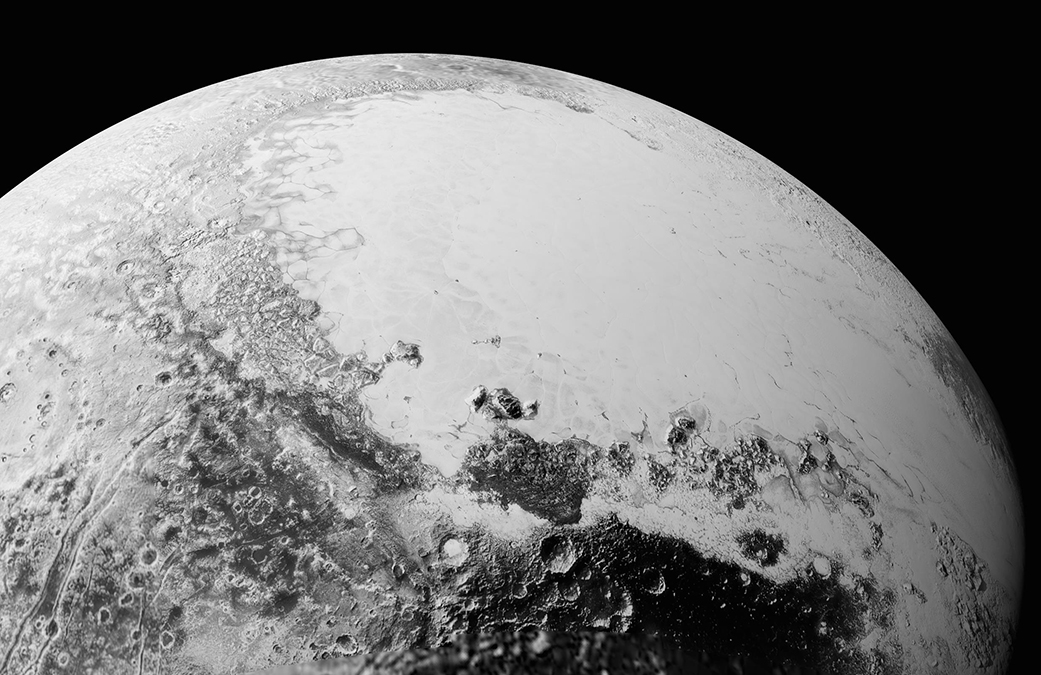

The underground ocean that produced some of the stunning features on Pluto's surface may still be splashing around beneath the crust today.

If Pluto's subsurface ocean had frozen over completely, it would have formed highly pressurized ice that would have caused the dwarf planet to shrink, according to new research. The canyons and valleys on Pluto seem to have formed as the dwarf planet swelled up, rather than as it shrank, indicating that a liquid ocean most likely sits beneath the thick ice crust today, researchers said in the study.

"Thanks to the incredible data returned by [NASA's New Horizons mission], we were able to observe tectonic features on Pluto's surface [and] update our thermal evolution model with new data," Noah Hammond, a graduate student at Brown University, said in a statement from the school. Hammond worked with his advisers — Amy Barr, of the Planetary Science Institute, and Marc Parmentier, also at Brown — to study the likelihood that a liquid ocean hides beneath Pluto's surface. [Pluto Has Ocean Beaneath Its Surface? Scientists Think So (Video)]

A wealth of oceans

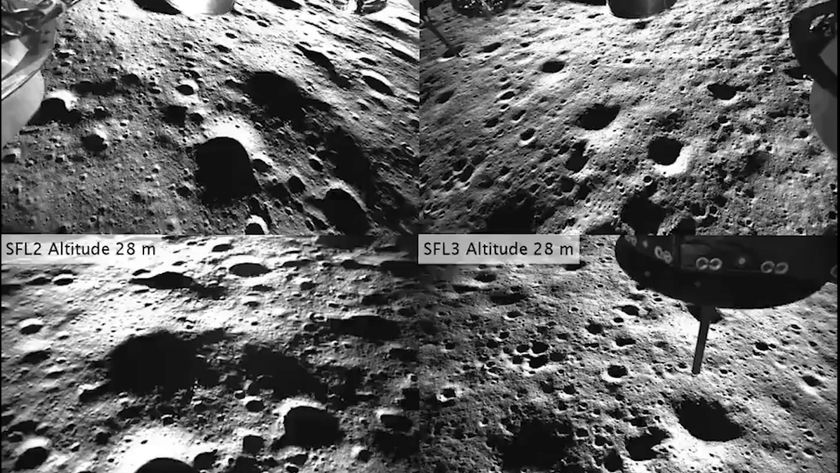

When the New Horizons probe flew past Pluto last July, its images of the dwarf planet's surface revealed deep faults, or fractures in the surface, hundreds of kilometers long, according to the statement from Brown. The long canyons appeared to form as Pluto's crust expanded, Hammond said. "A subsurface ocean that was slowly freezing over would cause this kind of expansion," he said.

It didn't take long for scientists to conclude that Pluto once housed an ocean, but the question of whether it had already frozen over remained. Using updated measurements of Pluto's diameter and density, Hammond's model revealed that a frozen ocean beneath the crust would have changed from conventional water ice to a more compact, crystallized structure known as "ice II." As the ice changed, the frozen ocean would have shrunk, creating an entirely different type of feature known as compressional fractures, which are not seen on Pluto's surface.

"We don't see the things on the surface we'd expect if there had been a global contraction," Hammond said. "So we conclude that ice II has not formed, and therefore that the ocean hasn't completely frozen."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ice II would have formed only if the dwarf planet's outer shell were at least 160 miles (260 kilometers) thick, putting sufficient pressure on the underlying ice, the statement said. Under the thinner shell, the ocean could have remained regular ice, not shrinking at all.

Hammond's model suggests that the shell might be closer to 190 miles (300 km) thick, thanks to high temperatures in the core, according to the paper. The addition of nitrogen and methane ice spotted on the surface of the tiny world may also help keep the water warm.

"Those exotic ices are actually good insulators," Hammond said.

That means oceans could lie not only inside tiny Pluto but also in other similar worlds in the far reaches of the Kuiper Belt, the sphere of ice and rock at the edge of the solar system.

"That's amazing to me," Hammond said. "The possibility that you could have vast liquid water ocean habitats so far from the sun on Pluto — and that the same could also be possible on other Kuiper Belt objects as well — is absolutely incredible."

The research was published online on June 15 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd