How Can the Universe Expand Faster Than the Speed of Light?

Paul Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University and the chief scientist at COSI Science Center. Sutter is also host of the podcasts Ask a Spaceman and RealSpace, and the YouTube series Space In Your Face.

How can the universe expand faster than light travels?

It seems like it should be illegal, doesn’t it? Over and over (and over and over) we're told the supreme iron law of the universe: Nothing — absolutely nothing — can go faster than the speed of light. Done. Nothing further needs to be said about the issue.

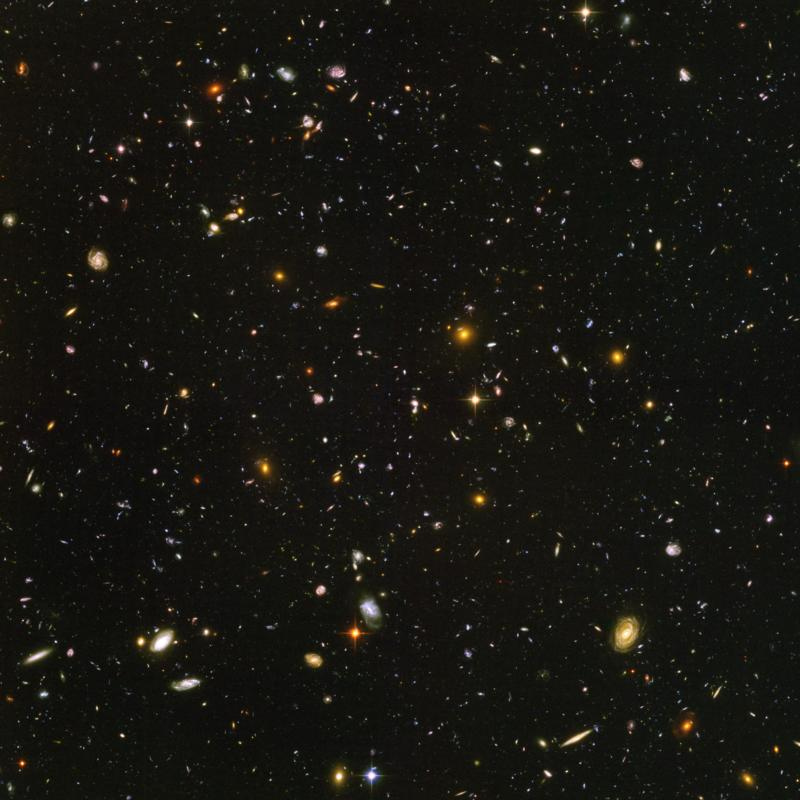

And then come the astronomers, always excited by the chance to mess up your comfort zone. They come barging in with a simple observation: Some galaxies are moving away from us…wait for it…faster than the speed of light. What gives?

The big picture

First off, it's important to note that we live in an expanding universe. Every day the galaxies get farther apart from each other — on average. There are slight motions on top of that general expansion, leading to instances such as the Andromeda Galaxy heading on a collision course for the Milky Way. But in general, in the biggest of pictures, the galaxies are getting farther away from each other.

A key feature of this expansion is how uniform it is. Imagine a bunch of folks standing around the edges of a stretchy piece of fabric, tugging at it. Let us assume they're choreographed well and are able to walk backward and pull at the same rate. You, standing in the middle, would correctly observe that your "universe" is expanding: any objects placed on that fabric would slowly move away from you.

Because stretchy stuff is stretchy, the objects on the fabric close to you would appear to move away with some speed, but the farther objects would appear to move faster. Even though the folks doing the pulling are moving at a constant speed, the apparent stretch changes with distance. I swear this is true; you can even try it for yourself at home!

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

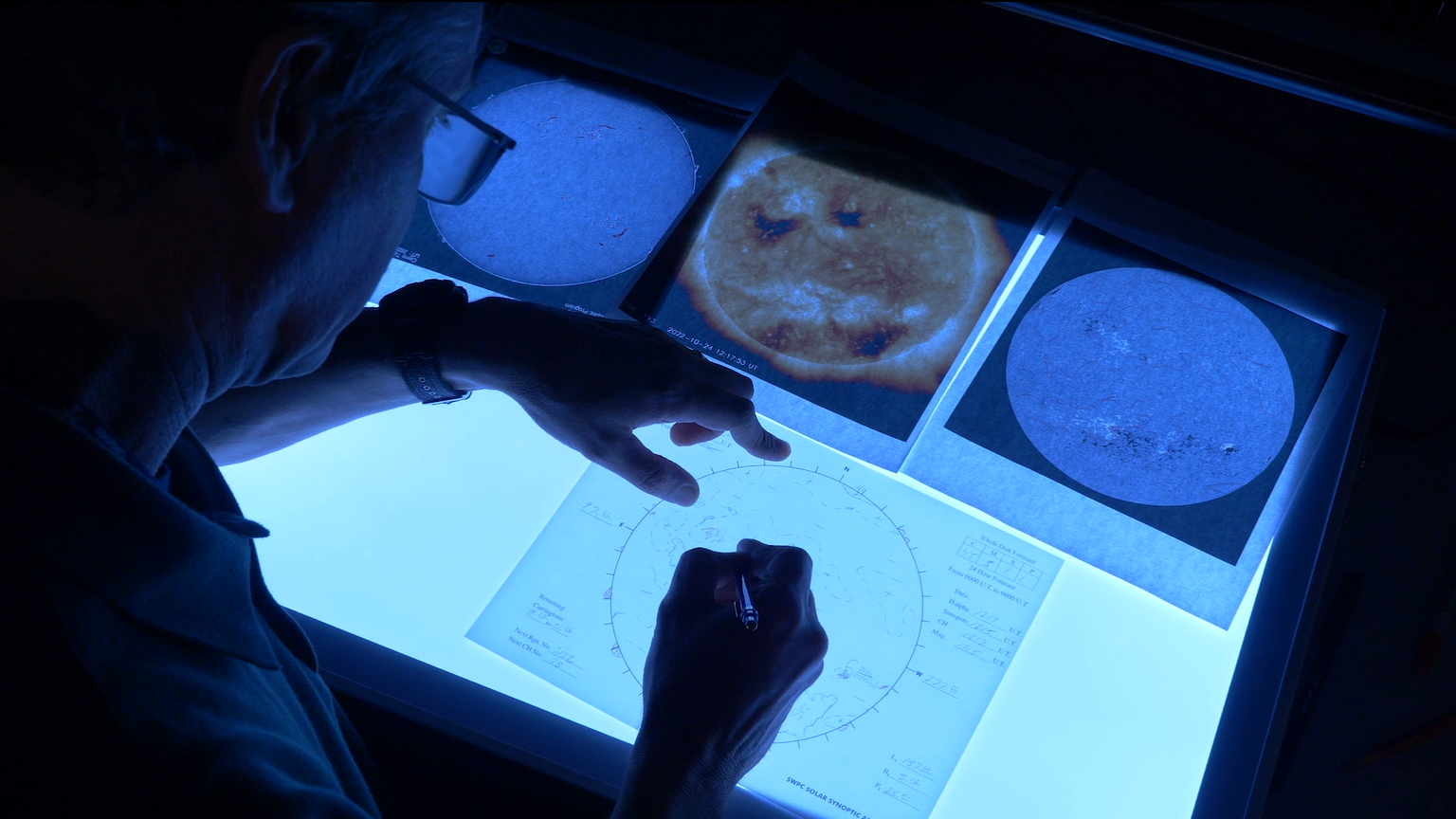

Now, let's jump to the universe. It's as if a bunch of folks are at the edge of the cosmos, gently tugging at the fabric of space-time, stretching it. Edwin Hubble was the first to measure the expansion rate. The number he got was way wrong, so I won't bother mentioning it, but good on him for trying. The more modern value is 68 kilometers per second per megaparsec, plus or minus a couple, but close enough.

I know, I know. You were probably following along just fine until that odd "per megaparsec" popped up. It's a distance: One megaparsec is 1 million parsec, which is 3.26 million light-years.

It means that if you look at a galaxy 1 megaparsec away, it will appear to be receding away from us at 68 km/s. If you look at a galaxy 2 megaparsec away, it recedes at 136 km/s. Three megaparsec away? You got it! 204 km/s. And on and on: for every megaparsec, you can add 68 km/s to the velocity of the far-away galaxy.

Over the limit

So it's easy enough to compute: At some point, at some obscene distance, the speed tips over the scales and exceeds the speed of light, all from the natural, regular expansion of space.

Yes, the movement of that galaxy can be interpreted as a "speed": you can measure the distance to it, wait awhile (to be fair, a really, really long while), and measure it again. Distance moved divided by time equals speed, and I guarantee you that the speed you measure can be faster than light.

No, this isn't a problem. [Watch as I explain in this video.]

The notion of the absolute speed limit comes from special relativity, but who ever said that special relativity should apply to things on the other side of the universe? That's the domain of a more general theory. A theory like…general relativity.

It's true that in special relativity, nothing can move faster than light. But special relativity is a local law of physics. Or in other words, it's a law of local physics. That means that you will never, ever watch a rocket ship blast by your face faster than the speed of light. Local motion, local laws.

But a galaxy on the far side of the universe? That's the domain of general relativity, and general relativity says: who cares! That galaxy can have any speed it wants, as long as it stays way far away, and not up next to your face.

It goes deeper than this. Concepts like a well-defined "velocity" make sense only in local regions of space. You can only measure something's velocity and actually call it a "velocity" when it's nearby and when the rules of special relativity apply. Stuff super-duper far away, like the galaxies we're talking about it? If it's not close, it doesn't count as a “velocity” in the way that special relativity cares about.

Special relativity doesn't care about the speed — superluminal or otherwise — of a distant galaxy. And neither should you.

Learn more by listening to the episode "How can the universe expand faster than light?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Mihail Etropolski, Nicolas Gregori, chris, and @archerelliott for the question that inspired this piece. Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.