A NASA spacecraft is about to start unlocking the many secrets of giant, mysterious Jupiter.

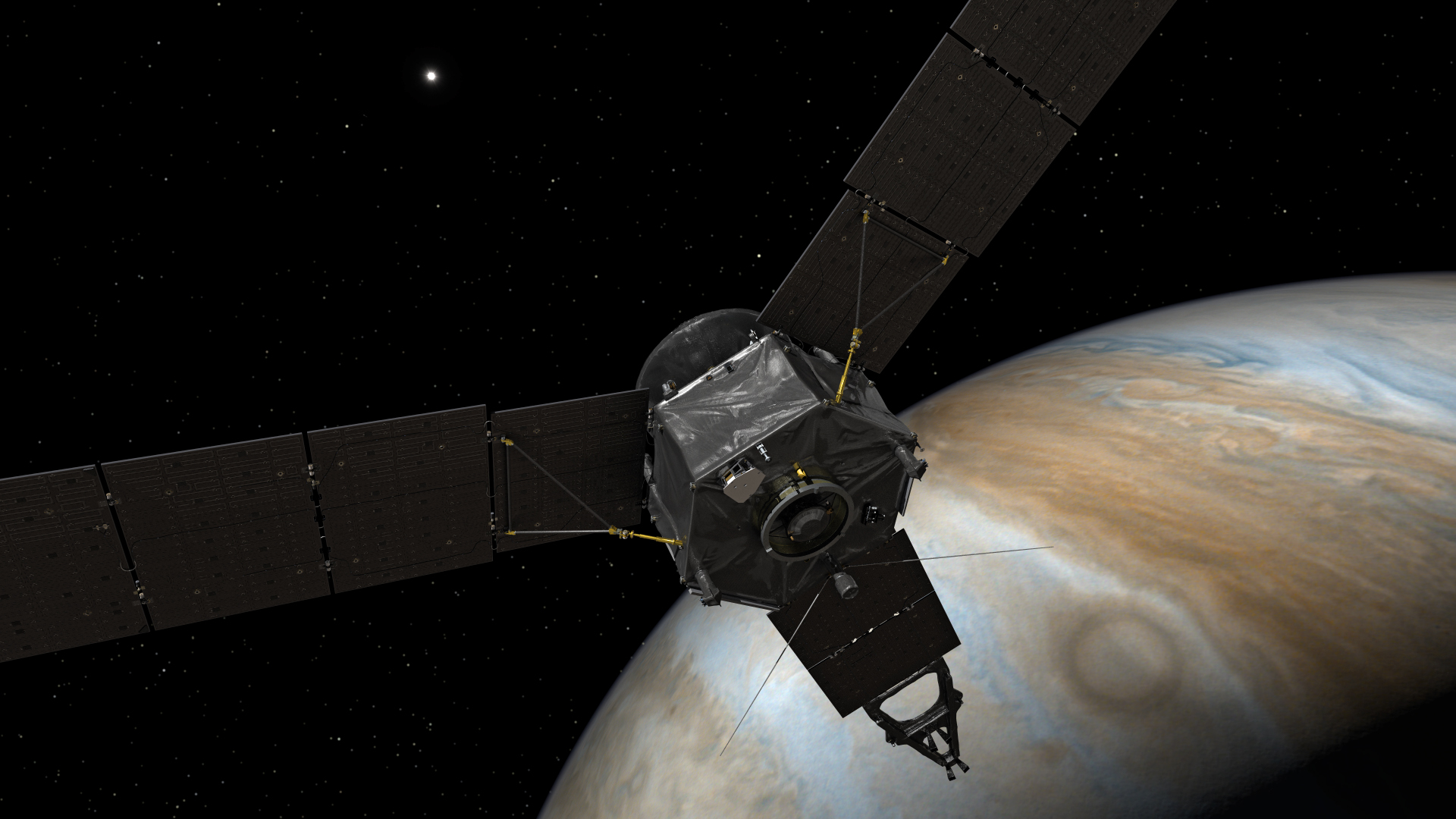

The Juno probe is scheduled to enter orbit around Jupiter on Monday (July 4), after a nearly five-year trek through deep space. Juno will then study Jupiter intensively over the next year and a half, peering deep inside the gas giant to help researchers better understand how it formed and evolved — information that should shed light on planet-formation processes in general.

"One of the primary goals of Juno is to learn the recipe for solar systems," mission principal investigator Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said during a news conference earlier this month. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

"Jupiter holds a very unique position in helping us learn about that recipe, because it was the first planet to form, so it gives you that very first step in the recipe," Bolton added. "What happened after the sun formed that allowed the planets to form? Because that's really the history of not only our system, but us, here at Earth."

Peering beneath Jupiter's veil

The $1.1 billion Juno mission takes its name from the wife of Jupiter, king of the gods in Roman mythology. The goddess Juno was able to see through clouds that her husband created to hide his mischief; similarly, the spacecraft will peer through Jupiter's thick atmosphere to get at the truths hidden within.

Juno launched in August 2011, then took a circuitous route through the solar system that included a speed-boosting close flyby of Earth in October 2013.

That long journey is nearly over. On Monday night, Juno will fire its main engines for 35 minutes, slowing down enough to be captured by Jupiter's powerful gravity. The solar-powered spacecraft will then gradually work its way into a highly elliptical, 14-day polar orbit that will bring it within 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of the giant planet's cloud tops at times — closer than any probe has ever gotten to Jupiter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Juno will then orbit the gas giant 37 times over the course of about 18 months, zooming repeatedly through Jupiter's intense radiation environment. (Juno's computer and other sensitive electronic parts are encased in a protective titanium "vault" that weighs about 440 lbs. or 200 kilograms, for shielding purposes.) [Juno Probe's Plunge Into Jupiter Orbit Fraught With Danger (Video)]

During the course of these orbits, Juno will use its nine science instruments to map Jupiter's magnetic field, gravity field and internal structure, among other things.

These measurements should reveal whether or not Jupiter has a rocky core — information that's key to understanding how and when the huge planet formed, Bolton said.

If Juno spots a core, "that implies that Jupiter formed after rocks started to form and ices started to form in the early solar system," Bolton said. "Alternatively, Jupiter may have formed like we think the sun did, which is just a collapse of the gas and dust, and you don't need any material in the center."

Juno will also determine the amount of ammonia, water and other substances in Jupiter's atmosphere, casting further light on the planet's formation and evolutionary history, mission team members have said.

Indeed, the composition of Jupiter is of great interest to researchers trying to understand the solar system's early days. Like the sun, Jupiter is composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, but the giant planet also harbors "heavier" elements that form the building blocks of rocky planets such as Earth, Bolton said.

"Something happened between the time the sun formed and the time Jupiter formed that allowed it to be enriched in these heavy elements," he said. "We don't know what happened, but it was very important, because the beginning of the process of how you create the terrestrial planets and life started already early in the solar system, when we saw Jupiter form."

Atmosphere and auroras, too

Juno will investigate other features as well before ending its mission with an intentional death dive into Jupiter's atmosphere in February 2018 (a move designed to ensure that the probe doesn't contaminate the ocean-harboring Jovian moon Europa, which is deemed one of the solar system's best bets to harbor alien life).

For example, the probe will map out the structure and movement of Jupiter's deep atmosphere as never before, and it will study the huge planet's magnetic environment as well.

As part of this latter work, Juno will sample the fast-moving charged particles near Jupiter's poles while also observing the gas giant's powerful auroras — a phenomenon also known, here on Earth, as the northern and southern lights — close-up at the same time.

"These are the strongest auroral emissions in the entire solar system," Bolton said. "Juno is flying right over those with a suite of instruments to investigate those aurora and the polar magnetosphere for the first time."

Comparing Juno's observations with information about the auroras of Saturn, Earth and other planets should allow researchers to get a better handle on how auroras work in general, he added.

In short, Bolton and his fellow mission scientists have a lot to look forward to after Juno finally arrives at Jupiter on Monday.

"It's been such a great journey, and I can't wait to get there," Bolton said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.