Meteorite Minerals Reveal Unexpected Collisions in the Early Solar System

In the very early solar system, newly formed massive planets like Jupiter and Saturn stirred up trouble in their cosmic neighborhood, causing smaller bodies to collide with each other, new research shows.

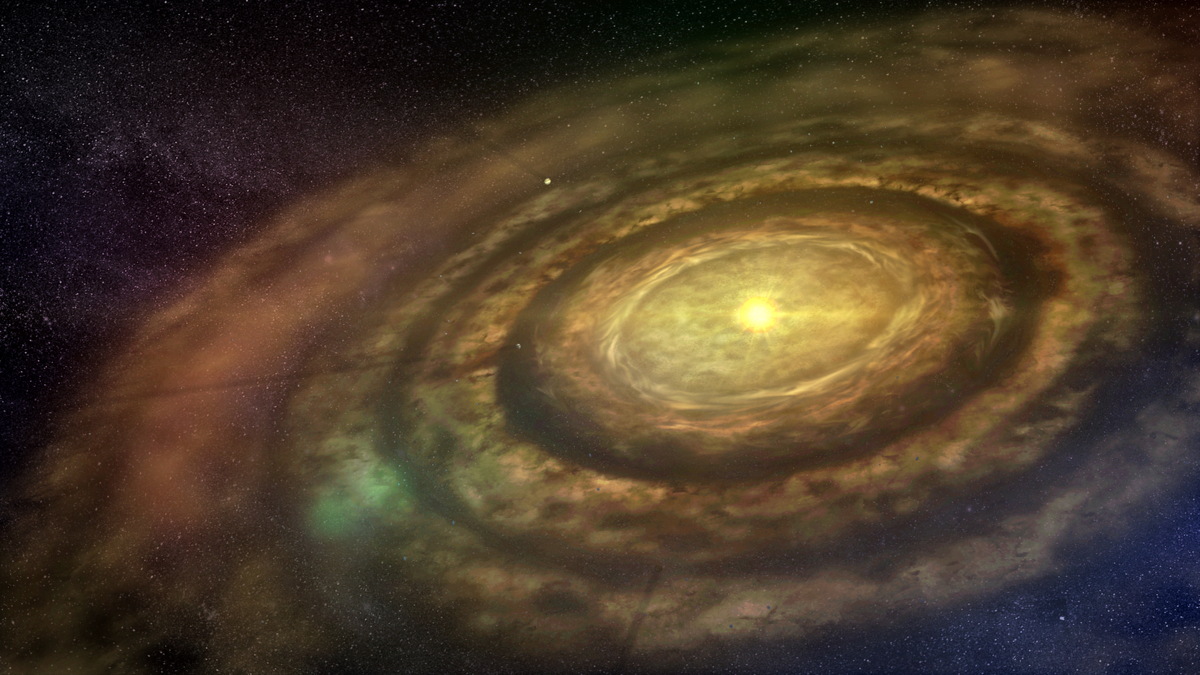

In the disk of material surrounding the very newly formed sun — a swirling cloud of dense gas and dust that eventually gave birth to Earth and the other planets — rocky bodies from the inner solar system experienced violent collisions with icy bodies from the outer solar system, according to new research paper published today (July 1) in the journal Science Advances. To reach each other, these clumps of matter would have traveled across billions of miles of space.

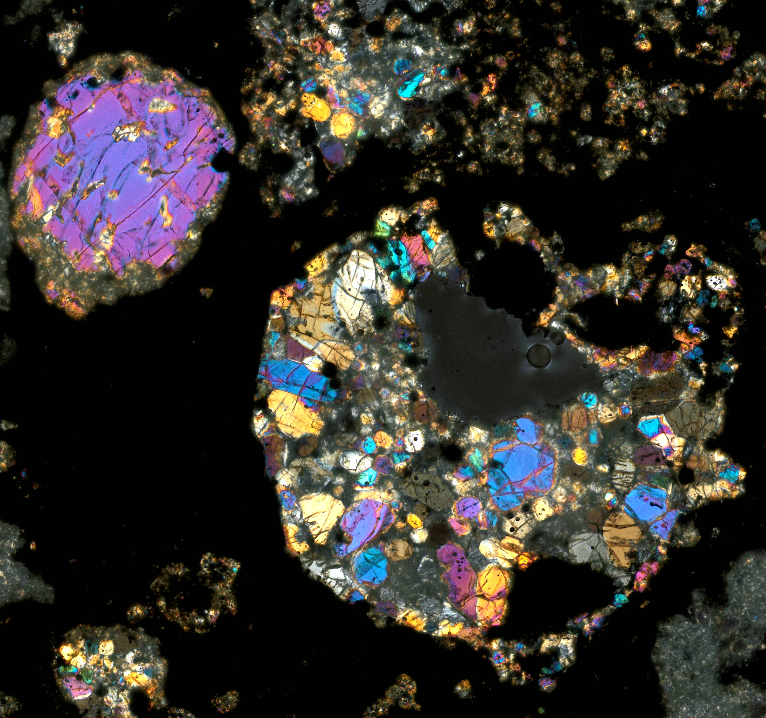

This discovery comes from a detailed analysis of twosamples of what scientists call chondrite meteorites that fell to Earth from space. Chondrites are among the largest class of meteorites and some of the oldest solid materials found in the solar system. These particular chondrite meteorites have their own names — Vigarano and Kaba — to distinguish them from others that have been collected. [Asteroids May Not Be Planet Building Blocks After All]

Vigarano and Kaaba also contain chondrules — small, round, glassy pellets embedded in chondrites. Chondrules formed when molten droplets rapidly cooled in outer space, and they constitute up to 80 percent of primitive meteorites, according to Yves Marrocchi, a cosmochemist at the Centre of Petrographic and Geochemical Research (CRPG) in France and lead author of the new study.

Chondrules were a part of the protoplanetary disk, from which Earth and the other planets in our solar system formed.

Prior research had suggested that magnetite — a primary mineral formed during chondrule formation — present in chondrules was the result of cold water circulation, according to Marrocchi. However, the new study found that the chondrules embedded in Vigarano and Kaba contain high-temperature magnetites.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This implies that these chondrules were formed under oxygen-rich conditions during impacts between planetesimals," Marrocchi told Space.com.

The composition and shape of the minerals present in the primitive meteorites revealed to Marrocchi and his colleagues that Vigarano and Kaba formed at high temperatures, he said. Marrocchi explained that, in order for magnetites to form at a high temperature, the environment of the protoplanetary disk needed to be oxygen-rich, which only occurs when there are collisions between planetesimals.

"When you produce a collision between small planets, you will produce what we call a plume of gas, which is just the vapors resonating from the collision," Marrocchi said, adding that the magnetites are then formed from the gases released during the collisions.

The results shed new light on the conditions of the early solar system. The researchers found the composition of these magnetites can only be explained by invoking a collision between rocky planetesimals from the inner solar system and icy bodies from the outer solar system. Using astrophysical models, the researchers then concluded that there was a lot of scattering between the inner and outer parts of the solar system, due to the early formation of giant planets, Marrocchi said.

"This implies that chondrules are not primitive dust formed in the disk but, to the contrary, are byproducts of collisions between planetesimals in the early evolution of the solar system," Marrocchi said.

Next, the researchers hope to better understand the kinetics, composition of gas, and duration of such collisions. If high-temperature magnetites are, in fact, found in other types meteorites, it will indicate that these collisions are the main process that drives chondrule formation, Marrocchi said.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.