SpaceX to Launch Vital New Spaceship Docking Port for Space Station

When SpaceX's robotic Dragon capsule launches on a new supply run to the International Space Station (ISS) on Monday (July 18), it will carry a vital piece of hardware in its trunk: the first of two new docking ports that will allow future private space taxis to link up automatically with the orbiting lab.

Right now, only Russian vehicles — crewed Soyuz spacecraft and robotic Progress freighters — can dock with the space station, using special ports on the Russian side of the orbiting complex. Cargo spacecraft launched to the American part of the station currently need to be grappled by space station crew.

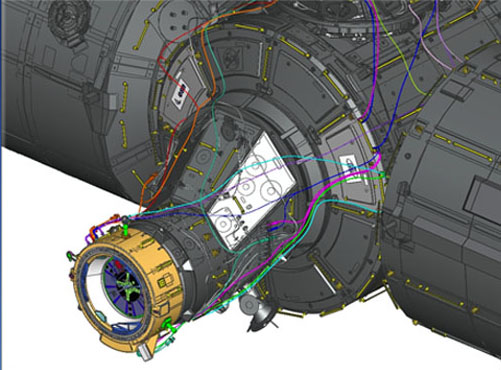

But that will change soon. The new docking ports, called International Docking Adapters (IDAs), follow a new international standard and are designed to let a variety of vehicles dock with the ISS on their own. [Spacewalkers Pave Way for New ISS Docking Port (Video)]

That's "the big darn deal about IDA," David Clemen, Boeing's director of development/modifications for the space station, said in a teleconference yesterday (July 13).

"There's an international docking system standard that was developed by the ISS partners to establish a standard for all future docking for not only the ISS but for future space vehicles," Clemen added. "And this will be the first component that was built to that standard and will be brought to ISS."

Boeing is one of two companies — SpaceX is the other — to have contracts with NASA to launch astronauts to the space station. Both SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule and Boeing's CST-100 Starliner capsule are on track to begin crewed flights to the station in 2017, NASA officials have said.

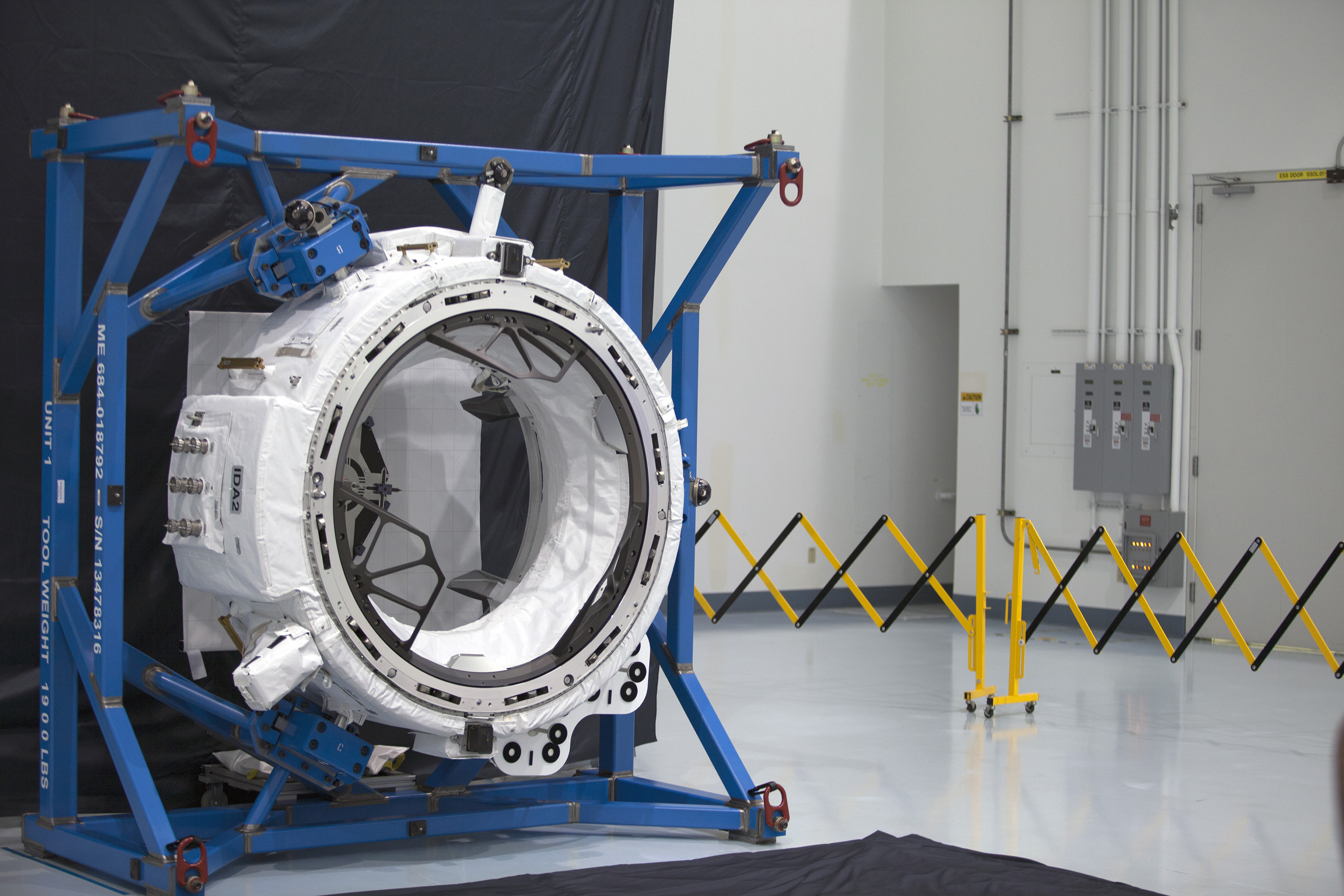

The IDA is a big ring that measures 3.2 feet (1 meter) tall; the inside is 5.25 feet (1.6 m) across. Its overall diameter, including sensors and other tools around the entryway, measures 7.8 feet (2.4 m), NASA officials said in a statement. The adapter's design was approved by representatives of Russia, Canada, Japan and the European Space Agency to be a standard interface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This will be the second try to get an IDA to the station. SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft was also carrying an IDA when it blasted off on a cargo mission in June 2015 — a flight that ended less than 3 minutes after liftoff, when its Falcon 9 rocket broke apart.

The adapter will travel to orbit in the rear trunk of Dragon, which NASA astronaut Jeff Williams will grapple with the space station's robotic arm. Later, once the craft is berthed to the station, the arm will pull the IDA from Dragon's trunk and move it about 1 foot (0.3 m) from the front of the port where it will be installed, NASA officials explained. Then, astronauts will perform a spacewalk to install it on the station, where it will fit over the top of an old space shuttle docking port. The second adapter, which will fly up separately next year, will fit over another such port.

"On the U.S. side, we have two large docking mechanisms that were used for the shuttle … and they're really not available anymore," Kirk Shireman, NASA's space station program manager, said during yesterday's news conference. "Those were built back by Russia years ago, and they don't use them on their side — they don't exist, basically, anymore. We needed to have a new mechanism."

Dragon's interior will carry about 3,800 lbs. (1,700 kilograms) of supplies and materials, including a lot of interesting components for science experiments aboard the orbiting lab. This gear includes a tiny DNA sequencer, to try sequencing DNA in space for the first time; living heart cells to test microgravity's effect on the beating heart; and a phase-change material heat exchanger that could freeze and thaw to help keep astronauts from getting too hot or too cold aboard the ISS.

Also aboard Dragon are microorganisms found in the area of the old Chernobyl nuclear reactor in Ukraine, which famously melted down in 1986. Researchers want to see how the microbes fare in microgravity, to inform strategies for radiation therapy.

Like the docking adapters, many of the space station experiments are testing technology that will be helpful as humans travel farther into space, NASA officials said.

Shireman discussed how the adapters will have uses beyond the space station. For example, a similar adapter fitting the same requirements could be used with the Orion spacecraft in orbit near the moon, he said.

"This is the first piece, but [the use of] IDA and this international docking standard has a long future ahead of it," Shireman said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.