Viking at 40: How NASA Mission Brought Mars Into the Light

The world got its first up-close look at Mars 40 years ago today (July 20), when NASA's Viking 1 lander touched down on the Red Planet.

Viking 1 beamed home two photographs shortly after its historic arrival, then went on to capture the awesome vistas of Mars in many more images — and collect data that reshaped scientists' understanding of the Red Planet.

Viking 1 and its sister Viking 2, which touched down on Sept. 3, 1976, allowed scientists to learn a great deal about Martian landforms, rocks and soil, as well as the planet's interior structure, wind and atmosphere. The duo also famously conducted life-detection experiments whose results are still being debated four decades later. [Viking 1: The Historic First Mars Landing in Pictures]

Viking "is one of the greatest missions NASA has undertaken," Roger Launius, Associate Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., said during a NASA-hosted discussion of Viking's legacy on Tuesday (July 19). "There's no question about that."

The Soviet Union's Mars 3 lander achieved the first-ever soft touchdown on Mars in December 1971, but controllers lost contact with the spacecraft less than 20 seconds later. Mars 3 returned just one partial photo to Earth.

Twin missions

The Viking 1 and Viking 2 spacecraft — which launched in August 1975 and September 1975, respectively — were both composed of an orbiter-lander pair.

As the Vikings closed in on Mars, each lander separated and dove toward the planet, reaching speeds as high as 10,000 mph (16,000 km/h) before being slowed by the thin Martian atmosphere. Near the end of their descent, the landers leveled off into a glide, further slowing them to 10 percent of their fastest speed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A parachute then deployed, and the craft's heat shield separated and fell. The landers' legs deployed and began collecting information until the lander reached the ground; the final descent was slowed by the firing of retrorockets.

Viking 1 touched down on July 20, 1976 on the western slope of Mars' Chryse Planitia region, while Viking 2 landed 6 weeks later, in an area called Utopia Planitia.

The original plan called for the orbiters and landers to function for 3 months at Mars, but they all far outlived their warranties: The Viking 2 orbiter and lander kept operating until July 1978 and April 1980, respectively. The Viking 1 orbiter lasted until August 1980, and the Viking 1 lander kept working until November 1982. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

First glimpses of an another planet

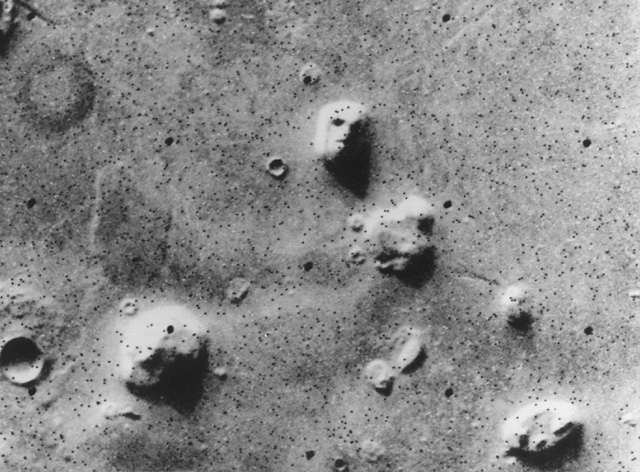

The Viking program provided a treasure trove of information about the Red Planet. The two orbiters studied the widespread volcanoes across the surface, for example, and identified an array of features that seemed to have been formed by past flows of liquid water.

The Viking orbiters' detailed stereo images of Valles Marineris, which dwarfs Earth's Grand Canyon, suggested that the enormous system of chasms was created not by a huge river but by tectonic shifts in the Martian crust.

Furthermore, the orbiters' imagery, combined with infrared data, provided insight into how the Martian poles changed seasonally. The orbiters also mapped water vapor across the planet, finding it to vary based on the location, season and time of day.

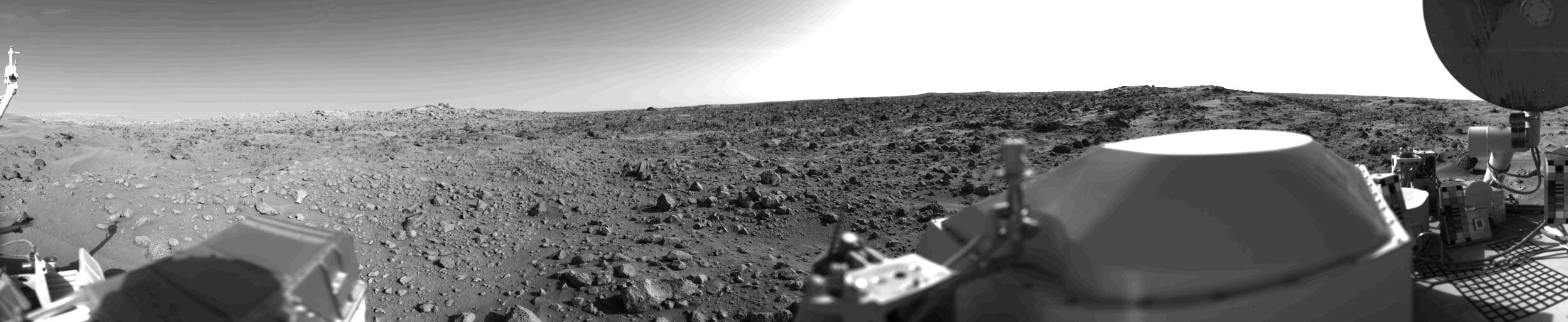

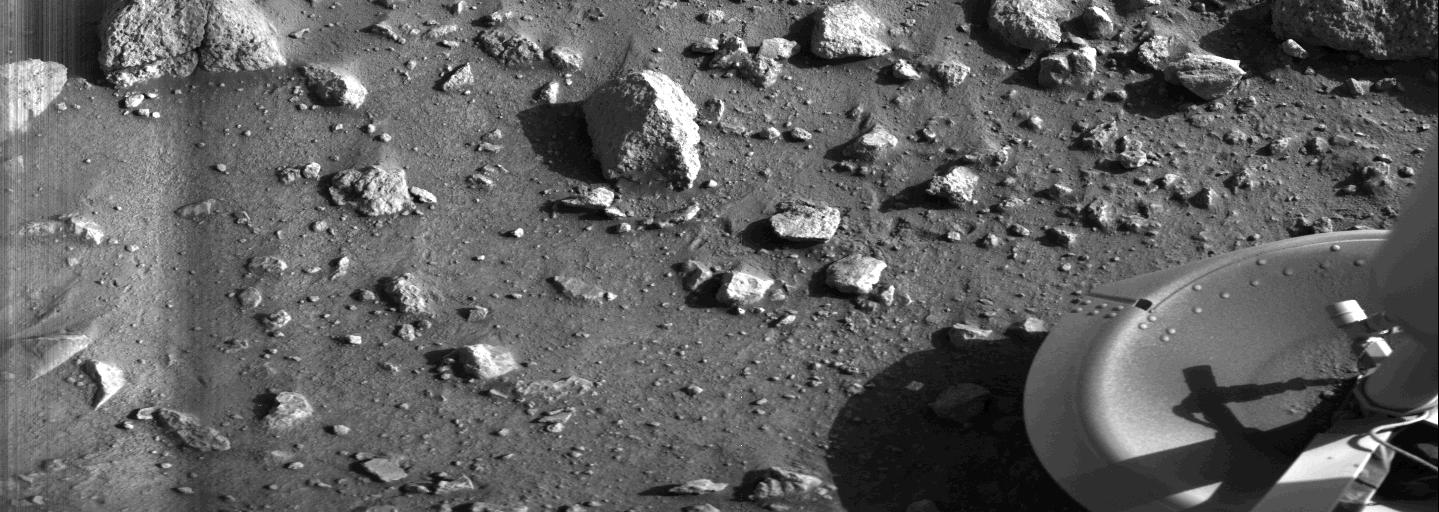

When the Viking 1 lander reached the ground, engineers commanded it to take two snapshots before going to sleep for the night, so the mission would have something even if the spacecraft never woke up. The first photo captured the soil beneath Viking 1, along with one of the lander's feet. The second, a panoramic shot, captured the Martian landscape.

The following day, Viking 1 returned the first color photo of Mars. The mission team anticipated calibrating the raw footage, but they failed to take into account the intense public interest in the photos, according to the NASA History Series book "On Mars: Exploration of the Red Planet," by Edward Ezell and Linda Ezell.

Due to public demand, the first color images from Mars were shown on TV within 30 minutes of their receipt at mission control. The mission team therefore didn't have time to calibrate the image properly and relied on human intuition, which resulted in Mars sporting an Earth-like blue sky in the image.

When imaging team member James Pollack said during a press conference on July 21, 1976 that the Martian sky was actually pink, he was greeted with "friendly boos and hisses," Ezell and Ezell wrote in "On Mars."

The initial Viking 1 photos revealed a vast, desert-like scene in greater detail than had been seen by previous spacecraft, such as NASA's Mariner 9 orbiter. The photos showed a varied terrain with diverse geology, and what appeared to be a variety of rocks littering the surface.

The reddish haze of the Martian sky came from dust swirling in the atmosphere. Over the next year, data from the Viking landers would reveal that, while the colors shifted somewhat, the sky retains its overall reddish tint.

The landers observed the weather on the Red Planet, which is far simpler than that of Earth, though not stagnant. Temperature and pressure, for example, varied through the seasons.

Vikings' seismometers measured not only the shaking of the ground but also the movement of the wind and incoming cold fronts. Viking 2's seismometer picked up magnitude-3-level marsquakes, though the failure of Viking 1's instrument kept scientists from determining their origin. Still, the team was able to determine that the crust beneath Viking 2 was between 8.7 miles and 11.2 miles (14 to 18 kilometers) thick.

The Viking landers dug trenches in the soil and revealed material unlike any found on Earth. By measuring the dimensions of the trenches and how much material collapsed, mission scientists estimated the soil's cohesion to be similar to that of wet sand.

Unlike Earth, modern Mars has no liquid water on its surface, leading some researchers to suggest electrical properties caused the material to cling together. Viking experiments also revealed magnetic particles in the dust and soil of Mars, indicating that the planet's red color comes from highly oxidized iron.

The hunt for life

Perhaps the most famous Viking experiments are the most controversial — the life-detection studies. Each lander carried the same three biology experiments. A gas-exchange experiment looked for evidence of microbe metabolism; the "labeled-release experiment" tried to detect decomposed organic compounds; and a "pyrolytic-release" experiment looked for the synthesis of organic matter in the soil. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

These experiments quickly got a lot of people excited, for they picked up possible signs of microbial activity. But NASA ultimately ruled the results inconclusive, and the unusual readings were deemed to have most likely come from terrestrial contamination. Not all of the scientists on the team agreed with this assessment, however.

Some recent studies indicate that Viking might have detected organic material, the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it (though a 2006 study, which probed Mars-like environments on Earth, suggested that the landers weren't sensitive enough to detect the organic material they were looking for).

In 2008, NASA's Phoenix Mars lander discovered perchlorates, a type of chlorine-containing compound. When Viking's pyrolytic-release experiment cooked its soil samples, it found chlorine compounds that were explained as contamination from the lander.

However, in 2010, a team of scientists, including Chris McKay of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, traveled to the Atacama Desert in South America and added perchlorates to microbe-filled soil there. They then analyzed the sample the same way the Viking landers did — and found the same chlorine compounds observed by Viking.

If Viking did indeed find organic material, it could be a sign that life might exist beneath the Martian surface. The landers dug only a shallow trench, however, so any organic material there would need a way to shield itself from harmful radiation (which is intense on Mars because the planet lacks a global magnetic field and thick atmosphere). Still, the findings have the potential to prompt changes in how humans look for life on other worlds, researchers have said.

"This doesn't say anything about the question of whether or not life has existed on Mars, but it could make a big difference in how we look for evidence to answer that question," McKay said back in 2010.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd