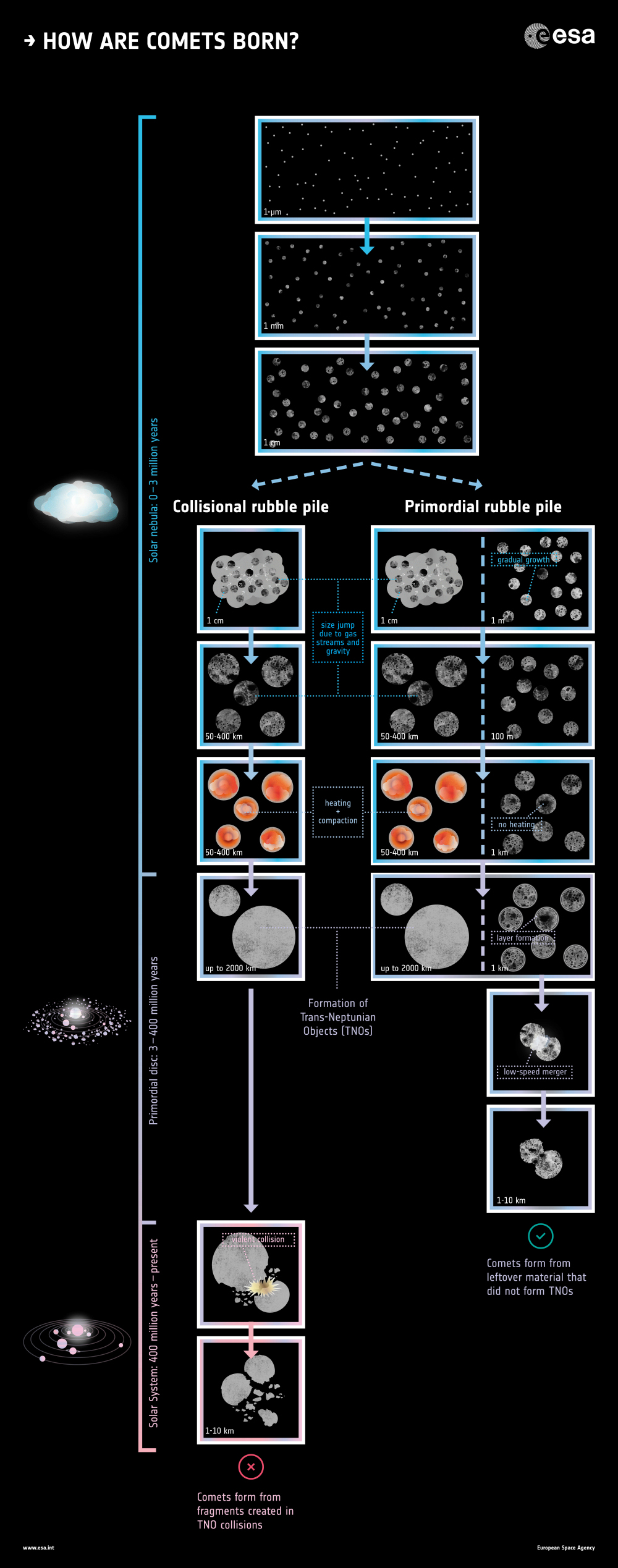

Comets are pristine remnants left over from the solar system's formation 4.6 billion years ago, rather than younger fragments created by collisions between larger bodies, a new study suggests.

The finding could lead to a better understanding of how the solar system took shape and evolved, researchers said.

"Comets really are the treasure troves of the solar system," Matt Taylor, project scientist for the European Space Agency's comet-hunting Rosetta mission, said in a statement. [Europe's Rosetta Comet Mission in Pictures]

"They give us unparalleled insight into the processes that were important in the planetary construction yard at these early times and how they relate to the solar system architecture that we see today," added Taylor, who was not involved in the new study.

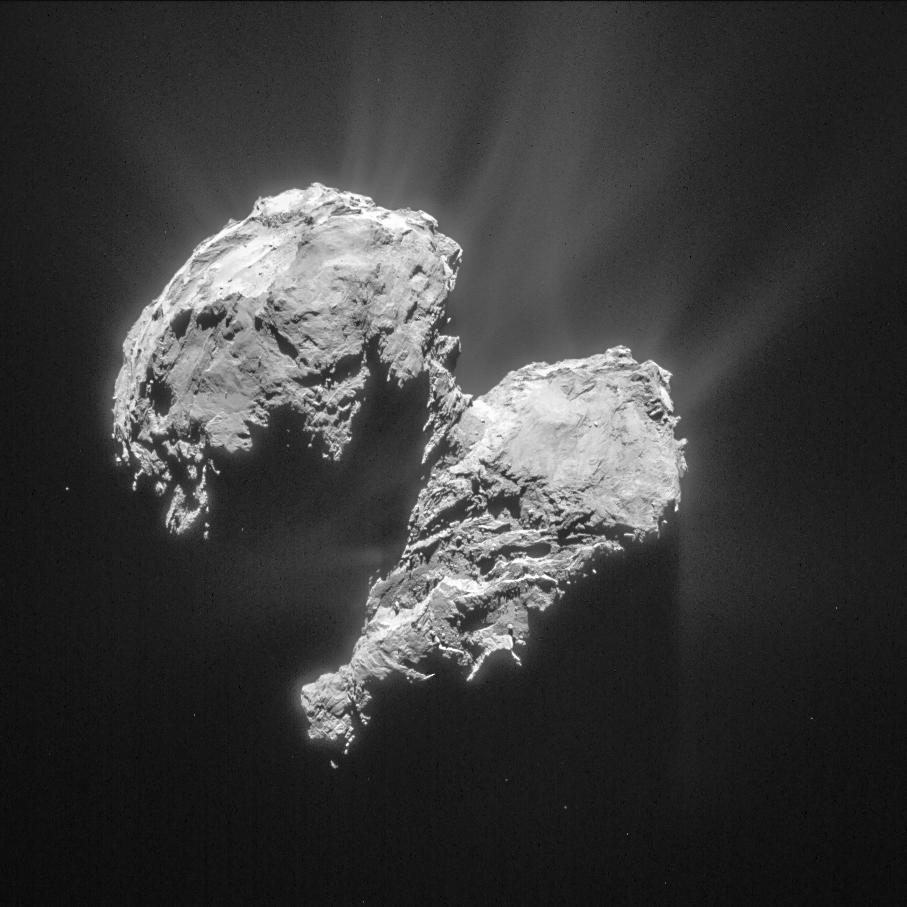

Study team members analyzed observations made by Rosetta, which has been orbiting Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko since August 2014.

They also studied meteorites, data from NASA's comet-sampling Stardust mission, and observations of distant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), moons of the giant planets, and other bodies in the outer solar system made by a variety of spacecraft and ground-based telescopes.

These data — as well as modeling work that investigated thermophysics, orbit evolution and collision physics, among other phenomena — strongly support the notion that comets are primordial, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

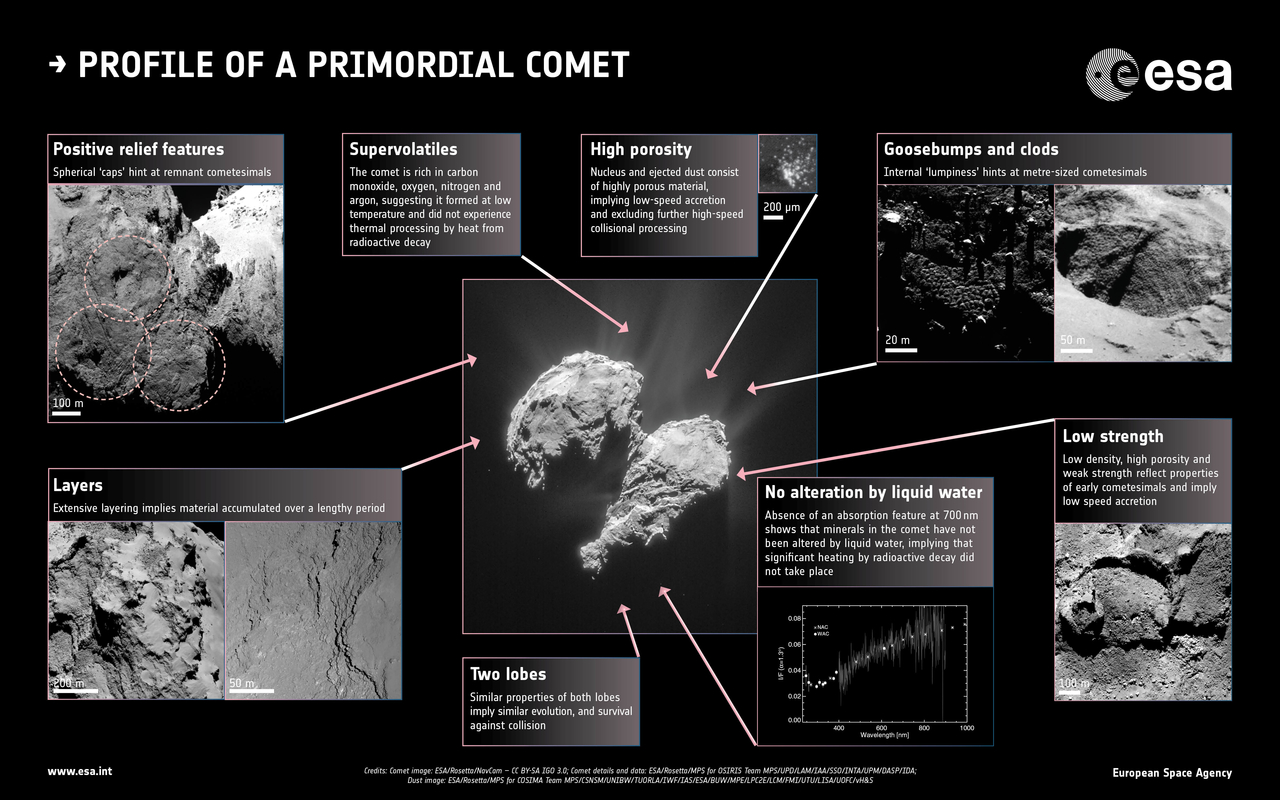

For example, Rosetta's measurements have shown that Comet 67P's interior is extremely porous and low-density. If the comet had formed and grown via violent collisions, as the primary competing comet-origin hypothesis holds, its insides would instead have been quite compacted, study team members said.

Rosetta's observations also revealed that 67P is rich in volatile substances such as carbon monoxide and oxygen, and that the comet's surface has been altered little if at all by liquid water.

These characteristics strongly imply that the comet formed in an extremely cold environment over a long period of time, and that it was not subject to significant "thermal processing," researchers said.

"Comets do not appear to display the characteristics expected for collisional rubble piles, which result from the smash-up of large objects like TNOs," study leader Björn Davidsson, of Uppsala University in Sweden and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the same statement. "Rather, we think they grew gently in the shadow of the TNOs, surviving essentially undamaged for 4.6 billion years."

TNOs likely did play a role in the evolution of comets, however. For example, study team members think that, in the solar system's early days, TNOs' gravitational tugs stirred up cometary orbits, causing some of them to bump into, and merge with, each other. (Comet 67P is thought to be the product of such a long-ago merger.)

"Our new model explains what we see in Rosetta's detailed observations of its comet, and what had been hinted at by previous comet flyby missions," Davidsson said.

The new study was published online Thursday (July 28) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.