How Genesis Crash Impacts Mars Sample Return

NASA's Genesis sample capsule not only stirred up dust and dirt when it crash landed in Utah last week, but also debate concerning the return to Earth of future extraterrestrial samples - specifically from Mars.

While the high-speed impact of the return canister was not planned, the capsule's design did permit the survival of some samples. However, due to a breach of the science canister caused by the crash, the space specimens were contaminated once exposed to Earth's atmosphere.

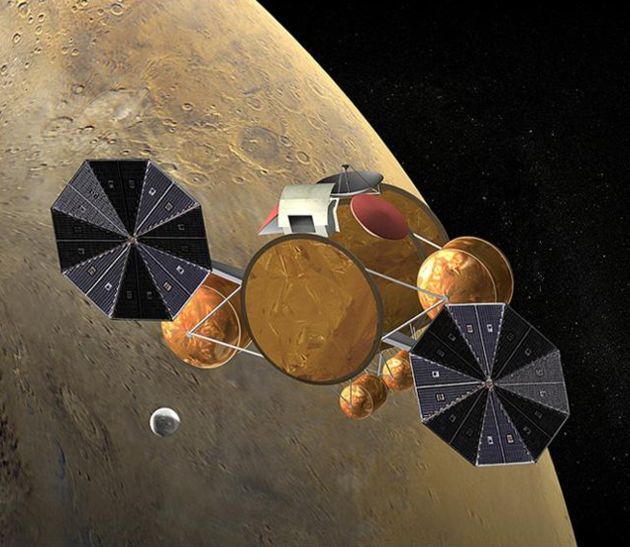

The Genesis probe, along with the homeward bound Stardust spacecraft carrying bits of a comet and interstellar particles, serve as precursor missions to snag, bag, and lug back to Earth select pieces of Martian real estate.

NASA engineers and scientists have been grappling for decades with methods, procedures, and the price tag for robotically returning Mars samples.

One concern is that Martian samples could contain microbial life. Whether that's the case or not, great care in handling specimens of Mars is a high priority -- not only to protect our planet from virulent biology, albeit a low probability, but also guarding the samples from Earth contamination.

The desert dust kicked up by the Genesis is settled as scientists work to retrieve some of its precious cargo. But talk about how best to orchestrate a future Mars sample mission is far from coming to rest.

Trashed and twisted hardware

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Genesis sample canister augured into the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR) at a speed of nearly 200 miles per hour (322 kilometers per hour). Onboard was a treasured stash of solar wind samples, embedded in breakable collector arrays.

With the capsule successfully rocketing through Earth's atmosphere, the plan then called for a mid-air helicopter recovery of the sample return capsule underneath an unfurled parafoil - a wing-like parachute.

But the parachute system failed to deploy. The return sample canister was banged up and severely damaged by the high-speed impact, leaving scientists to pluck through trashed and twisted hardware in the hopes of salvaging science data.

"We'll have to wait and see what the results and lessons learned from the Genesis mishap reviews are to see how they will affect Mars Sample Return designs," said Mark Adler, Mars Exploration Rover Mission Manager and an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Maintain containment

As currently envisioned, the Mars Sample Return mission uses a completely passive entry vehicle -- that is, hardware holding the specimen canister would be aerodynamically stable through landing on Earth. The MSR entry craft would not use or require a parachute, Adler explained.

"The samples of Martian rock and soil would be in a container designed to withstand the impact and maintain its integrity as well as the integrity of the samples," Adler said.

This design has been the lead candidate for about seven years, and a full-scale model was drop-tested at UTTR in 2000, he said.

A Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission is at least nine years away, so statements about the MSR final design should be taken "with the appropriate-sized grain of salt," he noted.

Photo Gallery of Genesis Mission

Complete Genesis Coverage

"Furthermore, public review and input on the environmental impact of MSR would be required before a final decision could be made to proceed with the mission," Adler told SPACE.com.

"It is clear, though, that the Genesis experience bolsters the previous conclusion that an MSR entry vehicle must be designed to maintain containment of the samples in the event that a parachute or any other entry, descent, and landing deployment or actuation fails," Adler said.

Breached canister

Seeing that the Genesis sample canister was breached and its contents exposed to Earth's biosphere, "the Mars Sample Return mission needs to be rethought entirely," said Barry DiGregorio, a research associate with the Cardiff Center for Astrobiology in the United Kingdom.

DiGregorio is also director for the International Committee Against Mars Sample Return (ICAMSR), an activist group established to increase public awareness regarding Mars-to-Earth transit of samples, along with any possible negative consequences that could occur due to an MSR canister either becoming opened unintentionally on impact, or lost during entry into the Earth's atmosphere.

In 2000, DiGregorio said, NASA was moving forward with its "faster, better cheaper" plan to return Martian soil samples as soon as 2003 and 2005 in a capsule design not unlike Genesis, with the exception that the MSR capsule would not use a parafoil or drogue chute. Instead it would use atmospheric friction to slow its descent and then directly impact the same general area in the Utah desert that Genesis did, he said.

Given the Genesis experience, DiGregorio argues that NASA's new Moon, Mars and beyond quest should include the establishment of a human-tended planetary sample

quarantine facility on the Moon as a part of any scientific outpost there.

"Examining Martian soil and rock samples on the Moon offers a 100 percent guarantee that Earth's biosphere would not become back-contaminated with any possible Martian microorganisms," DiGregorio said.

Exobiology perspective

John Rummel, Planetary Protection Officer at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., advised that there will likely always be a desire to bring back materials from elsewhere, and study that material in the most capable laboratories that are available, which are on Earth.

Genesis involved an in-air snatch, the softest way to land, due to the fragile nature of its collection devices and the requirement for molecular-level purity for its sub-microscopic samples of the solar wind, Rummel said.

NASA's Stardust mission will bring comet samples back to Earth in January 2006. The collection material, aerogel, is also fairly fragile, although the particles are bigger, Rummel said. Therefore, Stardust will land by parachute in Utah, sans the mid-air helicopter catch.

Rummel said designs being studied for the most recent analyses of a Mars sample return mission are anticipating a much more robust sample collection canister, and a strict containment requirement. Although a non-parachute landing would be hard, the sample canister will be cushioned inside the Earth Entry Vehicle, to minimize effects on both the sample and the container.

"Genesis did not have a planetary protection requirement for containment. There were no concerns about that mission from an exobiology perspective," Rummel said. "It is unfortunate that the parachute on Genesis failed to open, but sample return missions requiring strict containment will likely plan to do without one. The Genesis failure

makes that case pretty well...while emphasizing the importance of good navigation for safe sample return missions."

Martian somethings: how real?

"Everyone agrees that we must be as careful as possible with the Mars sample," said Wendell Mendell, Manager of the Office for Human Exploration Science at NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas.

The sample curation group at JSC believes they have the expertise and have access to other expertise sufficient to reduce any risk to an infinitesimal level, he said.

"The question is whether we want to spend billions or tens of billions of dollars to make the risk even more infinitesimal," Mendell said, noting that his views are his own and not official NASA positions.

Mendell said he is open to being persuaded that there is a real danger to bringing back a "Martian something" that could disrupt the Earth. "But I have never heard any argument based on logic and/or science that caused me to increase my personal concern. There is every reason to believe that 'Martian somethings' have landed on Earth with regularity."

Making a choice

As for DeGregorio's idea of a sample handling facility on the Moon, Mendell brought out a nagging question: What to do with the human crew that will eventually interact with the sample?

"If we keep the samples on the Moon for study, do we sacrifice everyone who studies them to minimize the risk even further? Where do we draw the line? Some people would like to draw the line at staying on Earth and keep away from space," Mendell explained.

A capsule can be built to withstand the impact speed experienced by the Genesis same return container, Mendell said. He added that scientists who want to study the sample do not want a hard impact on return and would insist on a mission design to minimize that possibility.

"A few years ago, we at JSC argued for a shuttle capture in order to safe the sample under human supervision before returning it to Earth," Mendell said. "Now, of course, everyone knows the shuttle can break up on return. Besides, the shuttle will not exist in 2013 when the sample is returned."

It is his personal view, Mendell said, that all of this boils down to making a choice: "One, forget about it, or two, do the best you can to minimize the risk and still make the event affordable to the space program."

- Genesis Mission: Crash Video and Complete Coverage

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.