Four years ago today, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity made one of the most dramatic and harrowing landings in the history of space exploration.

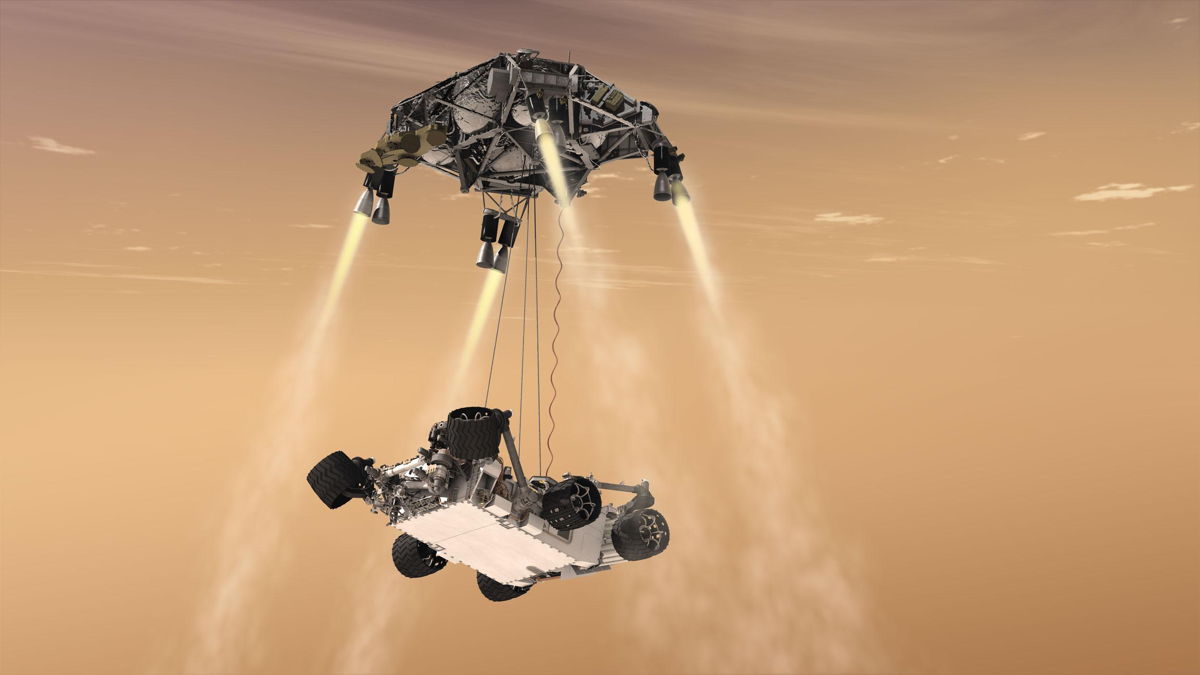

On the night of Aug. 5, 2012, a rocket-powered "sky crane" lowered the car-size Curiosity onto Mars' red dirt using cables, then flew off and crash-landed intentionally a safe distance away.

Curiosity team members had modeled this novel technique repeatedly using computers, but it had never been tested fully here on Earth, let alone employed on the surface of another world. [Curiosity Team Highlights 4th Year on Mars (Video)]

Still, everything worked perfectly at crunch time, and Curiosity soon began exploring the interior of Mars' 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater. The discoveries came fast: The rover found that the area near its landing site harbored a lake-and-stream system long ago, showing that at least some parts of the Red Planet could have supported microbial life in the ancient past.

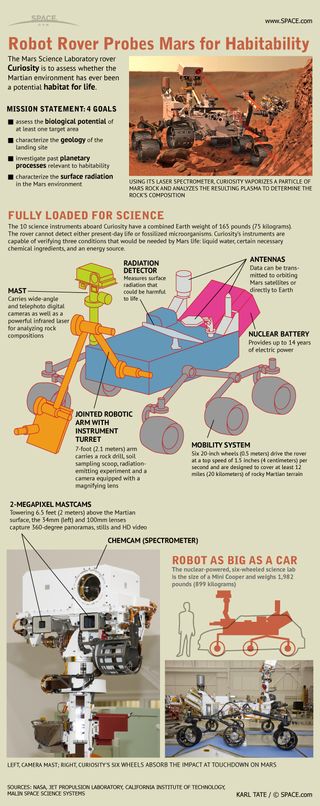

The main goal of the $2.5 billion Curiosity mission is to answer that very question.

"It was just an early home run that kind of took the pressure off, and allowed us to expand on that [discovery] for the next few years," Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, told Space.com.

Exploring a Martian mountain

After finishing up work near its landing zone in July 2013, Curiosity began the roughly 5-mile (8 km) trek to the base of Mount Sharp, which rises 3 miles (5 km) into the sky from Gale Crater's center.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mount Sharp's foothills had been Curiosity's ultimate science destination since before the mission's November 2011 launch. Mission team members want the rover to climb up through the mountain's lower reaches, reading a history of Mars' changing environmental conditions in the rocks as it goes.

Curiosity began doing just that when it reached Mount Sharp's base in September 2014, and the results so far are exciting, Vasavada said. The rover quickly came across a layer of mudstone, a type of rock formed by sediment accumulation at the bottom of a lake. And Curiosity is still examining that same layer, despite traveling about 100 vertical feet (30 meters) up the mountain.

While mission team members don't know the exact rate at which the mudstone was deposited, the extent of the layer suggests that the Gale Crater lake system persisted for millions, or perhaps even tens of millions of years, Vasavada said.

"We're talking significant periods of time — periods of time that are even significant for biology, if it ever took hold [on Mars]," he said. "The timescales involved are really kind of mind-boggling."

More mountaineering ahead

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft has identified three geological "units" above Curiosity that the rover's handlers want to explore before the mission comes to an end. (NASA recently extended Curiosity's mission through at least October 2018.)

One of these rock layers contains the iron-oxide mineral hematite, and another is rich in clays, which form in liquid water. The third unit contains healthy concentrations of sulfates, and could mark the beginning of a transition toward the cold and dry Mars that exists today, scientists have said.

Curiosity needs to gain another 1,000 vertical feet (300 m) or so to sample all three of these units, Vasavada said. Doing so will likely require putting an additional 5 miles (8 km) on the robot's odometer, he added.

Curiosity has incurred a significant amount of wheel damage since touchdown, but new driving techniques and avoidance of the most rugged terrain should allow the rover to go at least 5.6 more miles (9 km) on the Red Planet, Vasavada said. (Curiosity's odometer currently reads 8.43 miles, or 13.57 km, NASA officials said.)

The rover's science instruments are all still working fine, so Vasavada is eager to see what Curiosity finds over the next few years.

"Hopefully, the big results aren't all behind us," he said. "We still would love to find a really whopping signature of organic molecules, so that we get an idea of what was present on ancient Mars."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.