Vanishing Bottom-First: Map Reveals Thawing Areas Under Greenland

Two NASA satellites peering out over the Greenland ice sheet have helped researchers map areas thousands of meters beneath the thick, icy surface.

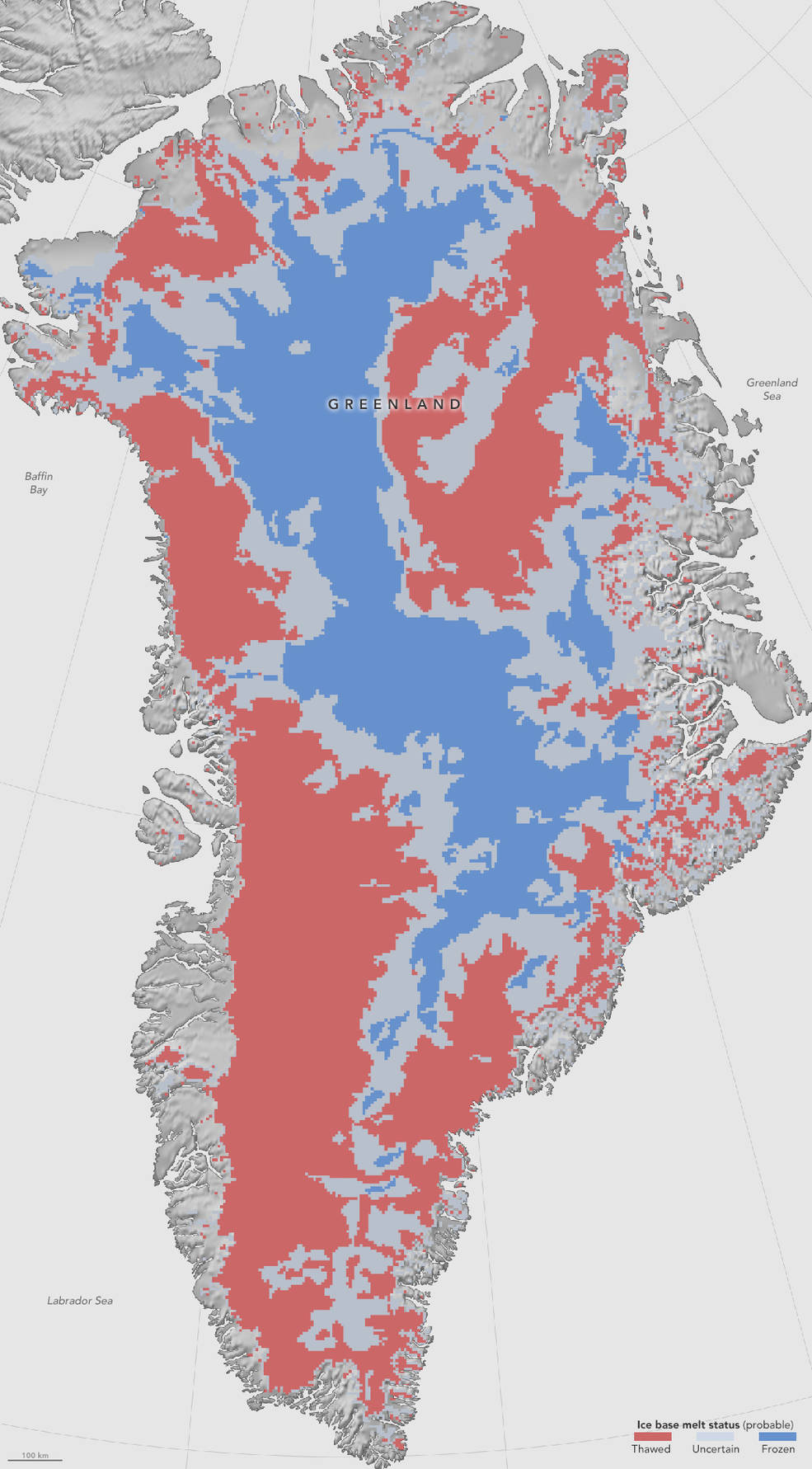

The new map, created by NASA scientists, is the first of its kind and shows regions underlying the ice sheet that are likely thawed or frozen, as well as areas where the state remains unknown. This information will help scientists better predict how quickly the rest of the ice sheet will melt in the future, NASA officials said in a statement.

"We're ultimately interested in understanding how the ice sheet flows and how it will behave in the future," Joe MacGregor, lead author of the new research and a glaciologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in the statement. "If the ice at its bottom is at the melting-point temperature, or thawed, then there could be enough liquid water there for the ice to flow faster and affect how quickly it responds to climate change." [Greenland's 'Grand Canyon' Revealed by Ice-Penetrating Radar (Video)]

The bottom of the Greenland ice sheet is often tens of degrees warmer than the surface due to some geothermal heat that rises from deep inside the Earth. This heat causes some areas to thaw, while other areas remain frozen solid.

Until now, scientists relied on only a few, isolated boreholes (dug directly into the ice sheet) to study what was going on at the bottom. The researchers of the new work, however, combined multiple methods, including observations from NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites. Using images captured by these two Earth-observing satellites, the researchers were able to look for areas of rugged terrain, which generally indicate that ice moved over the surface and carved a trail in a thawed bed at the bottom, NASA officials said in the statement.

The researchers also clocked the speed of the surface ice to see if it was exceeding its "speed limit" and moving exceptionally fast. That would mean the ice was no longer frozen to the rock beneath it, which would suggest the underlying area was thawed, according to the study, published July 23 in the Journal of Geophysical Research. The team also studied the individual layers of ice using radars onboard NASA's Operation IceBridge aircraft and used computer models to predict temperatures at the bottom of the ice sheet.

"Each of these methods has strengths and weaknesses. Considering just one isn't enough. By combining them, we produced the first large-scale assessment of Greenland's basal thermal state," MacGregor said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Based on the new findings, the researchers determined that the southwestern and northeastern areas (shown in red) are already thawed, while the central and western areas (shown in blue) remain frozen. However, there is still not enough data to conclude what is going on under a third section of the ice sheet, which remains grey on the map.

"I call this [new study] the piñata, because it's a first assessment that is bound to get beat up by other groups as techniques improve or new data are introduced," MacGregor said in the statement. "But that still makes our effort essential, because prior to our study, we had little to pick on."

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.