From Hospitable to Hellish: Venus May Have Supported Life

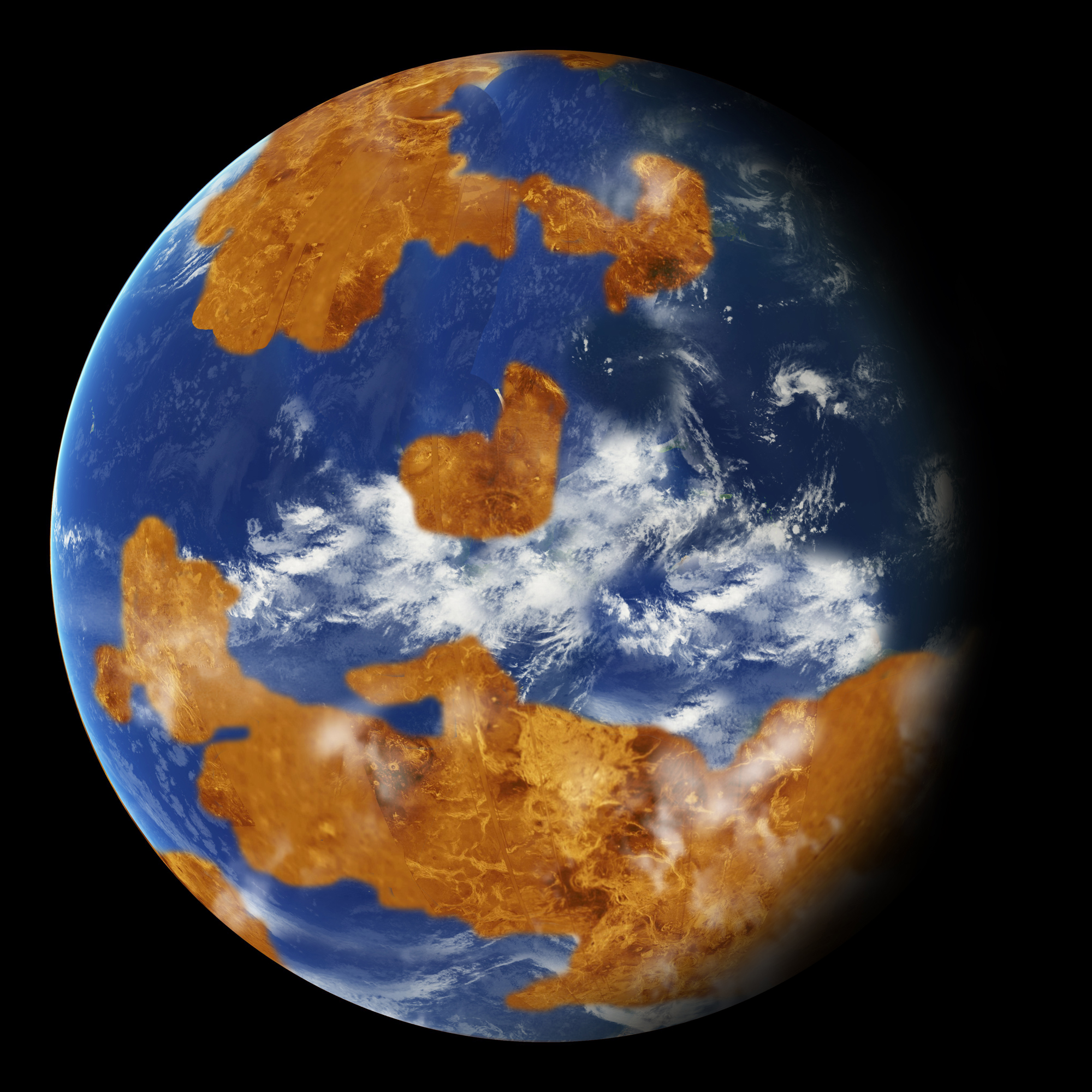

The "hellish" surface of Venus may have once been habitable, with a shallow ocean of liquid water, cooler surface temperatures and a thinner, Earth-like atmosphere.

Employing models similar to those used to predict climate change on Earth, NASA researchers from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) found that Venus — the second planet from the sun and the hottest world in the solar system — may have been able to support life during the first 2 billion years of the planet's early history, agency officials said in a statement.

Present-day Venus, on the other hand, is not quite as hospitable. The barren planet is known for having a suffocating carbon dioxide atmosphere that is 90 times thicker than Earth's, with clouds of sulfuric acid and extremely hot surface temperatures that reach 864 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius). [Venus: The 10 Weirdest Facts]

"Many of the same tools we use to model climate change on Earth can be adapted to study climates on other planets, both past and present," Michael Way, lead author of the new work and a researcher at GISS, said in the statement. "These results show ancient Venus may have been a very different place than it is today."

Venus and Earth are very similar in size and mass. And while the two planets are also thought to have formed from similar materials, those materials evolved differently because Venus is so much closer to the sun. Data from NASA's Pioneer Venus mission, which orbited the planet from 1978 to 1992, first suggested Venus had an early ocean that was evaporated by the sun.

When this happened, water vapor molecules in the atmosphere were split apart by ultraviolet radiation and the hydrogen escaped into space. As a result, carbon dioxide built up in the atmosphere, creating what researchers call a runaway greenhouse effect that trapped heat and led to the present-day conditions observed on the incredibly hot planet.

Venus also rotates on its axis much more slowly than Earth, with one day on Venus equating to 117 days on Earth. Previous studies have shown that Venus' slow rotation rate was likely due to the planet's thick atmosphere. However, the new findings, published Aug. 11 in Geophysical Research Letters, challenge this theory.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Instead, the new climate models showed that a thinner, Earth-like atmosphere on ancient Venus could have produced the same rotation rate that the planet has today, NASA officials said in the statement.

Using radar measurements of Venus' topography, taken by NASA's Magellan mission, the researchers simulated what the planet would have looked like billions of years ago. They did so by filling lowlands with water and factoring in a thinner atmosphere and dimmer, ancient sun.

The team hypothesized ancient Venus had a much drier landscape than Earth, which would have limited the amount of water evaporated from the oceans, as well as the resulting greenhouse effect from water vapor.

"In the GISS model's simulation, Venus' slow spin exposes its dayside to the sun for almost two months at a time," Anthony Del Genio, co-author of the study and GISS scientist, said in the statement. "This warms the surface and produces rain that creates a thick layer of clouds, which acts like an umbrella to shield the surface from much of the solar heating. The result is mean climate temperatures that are actually a few degrees cooler than Earth's today."

With cooler temperatures, cloud cover to shield the planet from the sun's bright rays and a shallow ocean, life may have had a chance to thrive on Venus. NASA officials noted that these finding will help researchers in their search for other possible habitable planets.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.