Why Did It Take So Long to Find Proxima b?

Over the past two decades, astronomers have discovered more than 3,200 exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system. They've found gas giants; rocky, Earth-like planets; and "Tatooine"-like planets with two suns. They've detected alien worlds as far as 13,000 light-years away from Earth. But until now, scientists had missed an Earth-size, possibly even habitable, planet that was, at least cosmically speaking, right under our noses.

Astronomers announced today (Aug. 24) that they've discovered an alien planet orbiting Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf just over 4 light-years away that is the nearest star to the sun. So why did it take scientists so long to introduce us to our neighbor?

It's not because they weren't trying. [Proxima b: Closest Earth-Like Planet Discovery in Pictures]

"I was looking exactly for this," said Michael Endl, an astronomer at the McDonald Observatory at the University of Texas at Austin.

Endl, who was part of the discovery team, previously led a seven-year campaign in the early 2000s to look for planets with similar masses to Earth's in the so-called habitable zone around Proxima Centauri using the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope in Chile. Back then, he found nothing.

"We could have found everything from two to three Earth masses in the habitable zone," Endl told Space.com. The newfound alien planet —at just 1.3 Earth masses —flew right under his radar (or telescope).

As the nearest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri seemed like a good place to look for exoplanets, which scientists now know are abundant. But until now, campaigns like Endl's had turned up empty-handed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new planet, known as Proxima b, was so elusive because it is a relatively small world that orbits a small star —one that's too dim to be seen from Earth with the unaided eye. Finding this alien world required a dedicated, intensive campaign to detect its very faint signal.

"For 10 years, we had the technical ability to detect this planet," said Guillem Anglada-Escudé, an astronomer at Queen Mary University of London who led the discovery team. "It's not a matter of refinement or technology here."

Finding a little wobble

Planets can exert a gravitational tug on their parent star as they orbit, causing the star to wobble around a center of mass. Astronomers can measure this wobble because of a phenomenon known as the Doppler effect, which describes the change in frequency of a wave as its source moves toward or away from an observer.

Police radar speed guns use this effect to detect how fast a car is moving. Astronomers can do something similar by aiming their telescopes to measure the light of a star, Endl explained. When a star is moving toward us, its light appears shifted toward the blue end of the spectrum, and when it's moving away from us, the light appears red-shifted.

Even a planet as small as Proxima b causes its parent star to wobble ever so faintly. But the tiny change in the star's velocity is close to the limit of what can be detected with today's astronomical instruments.

Proxima b orbits its parent star every 11.2 Earth days. During that cycle, Proxima Centauri wobbles accordingly, moving toward Earth at about 3 mph (5 km/h) —which is about the speed most people walk —and then away from Earth at the same speed.

Anglada-Escudéhad noticed the faint signal of this 11-day cycle during a previous campaign to observe Proxima Centauri in 2013.

But at the time, the data were not conclusive enough to say that Proxima Centauri had a planet. There's generally lot of other noise in this type of data, Endl said. The signal could, for example, come from the star itself, which is quite active and experiences frequent flares. [Alien World 'Proxima b' Around Nearest Star Could Be Earth-Like (Video)]

'Pale red dot'

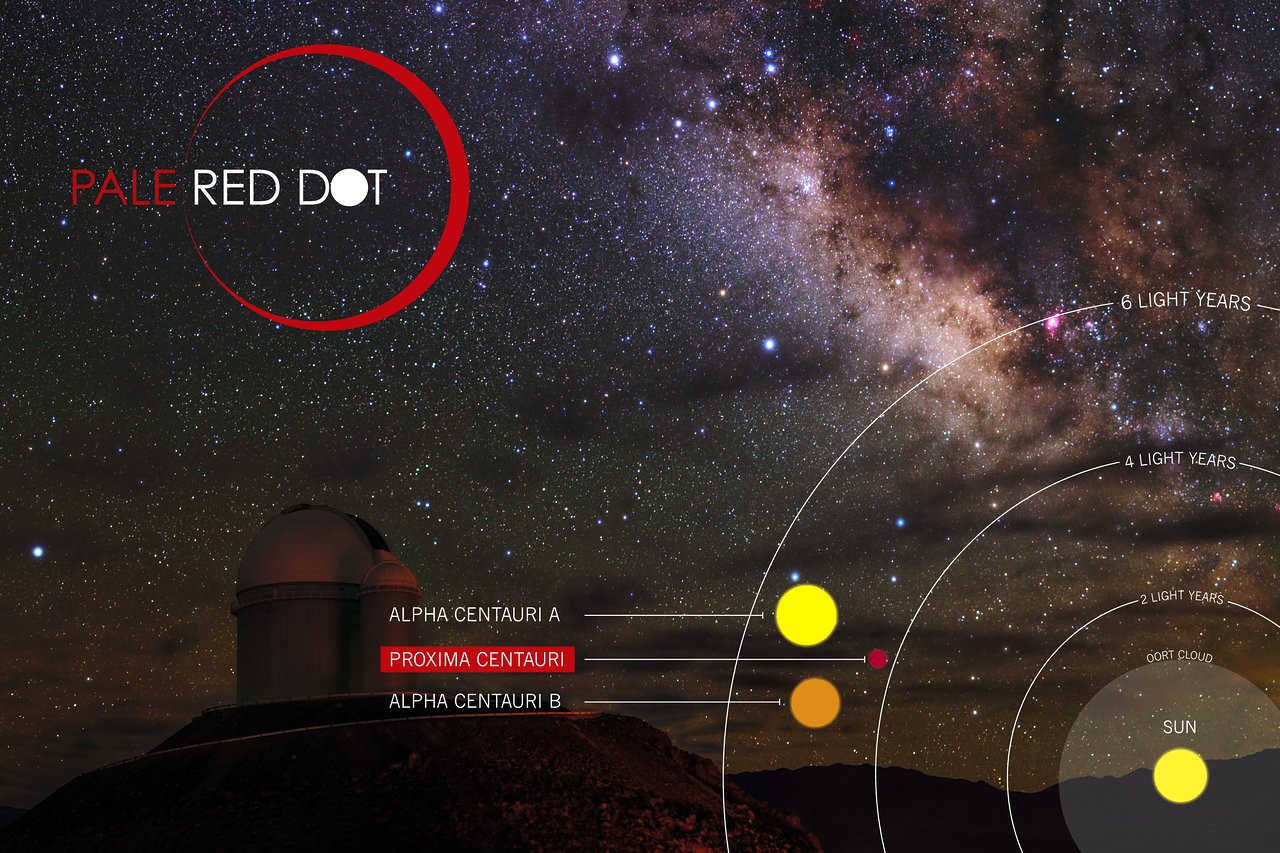

To rule out these possibilities, Anglada-Escudéthen launched a systematic search involving 30 other scientists, dubbed the "Pale Red Dot" campaign. The name plays off of Carl Sagan's famous "pale blue dot," the phrase he used to describe the tiny blue Earth as it appeared in an iconic photo of the solar system taken on Feb. 14, 1990, by NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft on its trek toward interstellar space. By contrast, a planet in the glow of Proxima Centauri would be bathed in red light.

Anglada-Escudéand his colleagues went hunting for an exoplanet around Proxima Centauri from January 18 to March 30 of this year at the ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile. The team's primary tool was the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher instrument, or HARPS, which normally would be useless at detecting a Doppler signal in a star as faint as a red dwarf. But the survey worked for Proxima Centauri because the star is so close to Earth, Anglada-Escudéexplained.

From their observations, the researchers gleaned that the mass of the alien world is roughly the same as Earth's and that the planet lies in the habitable zone, meaning it just might have the right conditions for life. They still have more work to do to confirm whether this planet actually has an atmosphere or water on its surface —features that would make it more Earth-like.

It might be possible to conduct further observations of Proxima b using other exoplanet-detecting methods, such as looking to see if it "transits" in front of its parent star from Earth's perspective.

"Now that we know the planet, we can predict when it's most likely to be in front of its star," Anglada-Escudésaid. "If that happens, that would be huge."

This technique had been attempted at Proxima Centauri before, without any luck. Indeed, discovery team members said there's just a 1.5 percent chance that Proxima b transits. If it is a transiting planet, however, scientists should be able to measure the spectrum of starlight as it filters through the atmosphere of Proxima b, which could contain crucial clues about the planet's chemical makeup.

"The excitement comes from the fact that we have a potentially habitable world," Endl said. "And the proximity of the star will allow us to do much more detailed follow-up observations of this planet."

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter @meganigannon. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.