Venus and Jupiter Imagined: From Galileo to Science Fiction

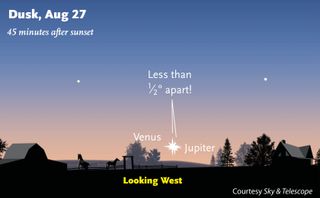

Venus and Jupiter will appear so close together in the sky this Saturday (Aug. 27) that, from some locations, the two planets will appear to almost touch. But as close as they may appear, these two planets have very distinct images in the public's perception — and that history stretches back centuries and has evolved greatly over time.

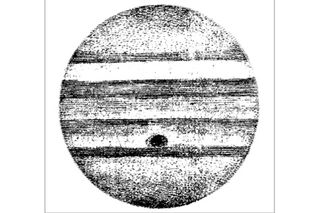

Venus and Jupiter were the first two planets to be systematically observed with telescopes. Through his observations in the early 1600s, Galileo Galilei transformed the way humanity saw Venus and Jupiter, and with them, the universe.

"With Galileo, those lights transformed into worlds," Edwin. C. Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, told Space.com. Previously, no one was able to see that the planets weren't just points of light, but disks. [Venus-Jupiter Conjunction 2016: When & How to See It]

Krupp, who has become an expert on ancient astronomy in his 40 years at Griffith, noted that Galileo, with his early telescope, discovered that Venus had phases, just as the moon does, proving once and for all that it was spherical and located closer to the sun than Earth was. This was a major discovery, because it showed that Venus had to be moving around the sun, and between the sun and Earth.

Up to that point, most people thought the Earth was at the center of the solar system, with the sun and planets orbiting Earth. Some of the planets appeared to move in one direction some nights, and then back in the other direction other nights — what is now called retrograde motion.

At the time, this backward motion was explained by epicycles: Each planet had a point that it would swing around, describing a small circle, even as it simultaneously circled the Earth. The system, invented by Ptolemy more than a millennium before, was unwieldy, but it did a decent job of predicting planetary motion. Galileo's observations fit better with the idea that Nicolaus Copernicus proposed in the 16th century: that the Earth and other planets go around the sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

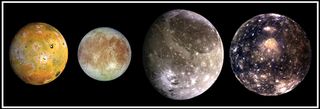

Galileo also discovered that Jupiter had moons. He found four: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The names weren't fixed until long after he died, but we still call those four moons the Galilean satellites in his honor.

Galileo's work sparked "a key transformation in human perspective," Krupp said. That transformation was only exceeded, in Krupp's opinion, by the dawn of the so-called space age in the 1950s, when humans could not only study the cosmos, but travel there.

Finding Jupiter's moons put additional cracks in the Earth-centric system of astronomy because astronomers had to acknowledge that the Earth was not the center of all motion, with all heavenly bodies revolving solely around it. Galileo also showed that Earth was no longer the only world that had a moon. If the other planets could have one, Earth was not unique in this regard.

But seeing the planets, even through a telescope, wasn't enough to solve the mysteries of what kinds of worlds these were. And that's where the human imagination filled in the blanks.

Venus: from jungle to hellscape

Krupp noted that before the dawn of the space age, astronomers tended to study stars; in the 1950s, the idea of a planetary scientist was in its infancy. So the very idea of applying models learned from geology on Earth to Venus was unusual.

"Part of it had to do with the relatively small population of astronomers engaged in those problems," he said. "Planetary astronomers were relatively few."

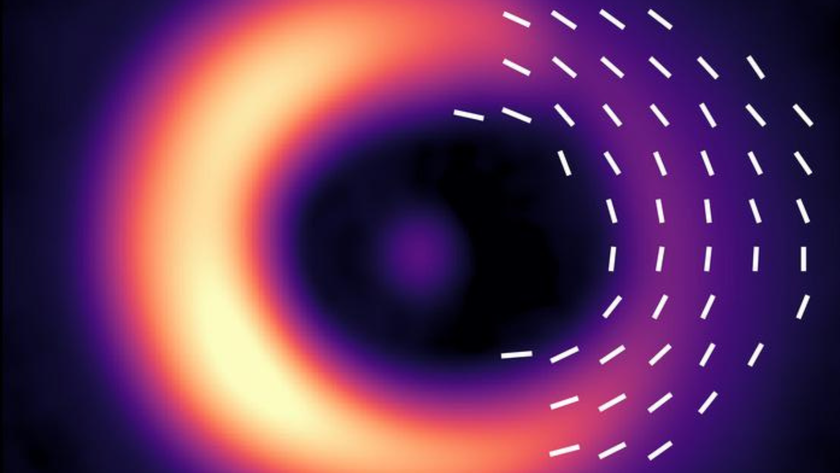

One limitation was technical:the telescopes available in the first half of the 20th century could only pick up so much detail from the ground. Covered in clouds, Venus looked like a featureless, white ball when viewed in optical light from Earth. (The pictures from space probes that show cloud structure are usually shot in ultraviolet light.)

Without the ability to sample Venus' atmosphere or observe the planet more closely, the best anyone could do was take spectrographs (which can reveal the chemical composition of clouds through the light they reflect) and temperature measurements of Venus. But Krupp said the temperature at the cloud tops of Venus didn't reveal anything about the temperature at the surface. Meanwhile, the composition of the planet's atmosphere was known to be largely carbon dioxide, but that was about all the information that was available until the early 1960s.

Breakthroughs came in the 1960s and 1970s when radar imaging revealed that Venus had a rough surface that was solid, and that the planet rotated very slowly.

Imaginations ran wild. Clouds, of course, had to be made of water, so most of the early ideas about Venus revolved around it being a wet planet.

"I credit Edgar Rice Burroughs," Krupp said, referring to the famed writer who created Tarzan and the Martian warrior John Carter. Burroughs posited that Venus was a jungle planet, but other writers — among them, C.S. Lewis, best known as the author of the "Chronicles of Narnia" series — ran with the ocean world idea. Some authors — notably, science-fiction legend Ray Bradbury — thought Venus might be a rainforest.

A succession of orbiters and landers, mostly the Soviet Union's Venera probes and the U.S.' Mariner missions, put to rest any notion of Venus as a planet that was essentially identical Earth, with a few tweaks. Surface atmospheric pressures on Venus are 90 times those on Earth, and it's hot enough to melt lead and zinc, they found. These missions also revealed that the clouds were largely made of sulfuric acid.

The discoveries showed that Venus was more alien than anyone had thought, and turned the popular imagination elsewhere.

"I think, pre-Venera, there was a lot of speculation about the conditions on the surface," Paul M. Sutter, an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University (and a frequent contributor to Space.com's Expert Voices section), said in an email. "If anything, Venera turned people off to the concept of colonizing or exploring Venus. Perhaps that's why there's so much focus on Mars now."

Jupiter gets a close-up

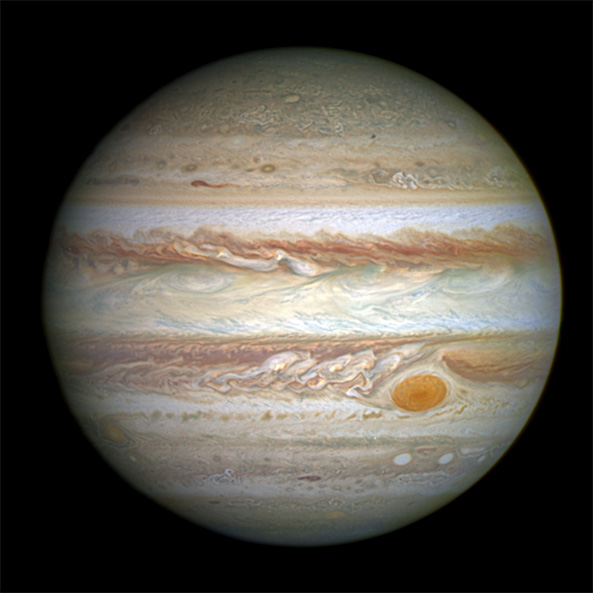

Jupiter, by contrast, never got quite the science-fictional treatment Venus did. Krupp noted that Jupiter's bands became visible through telescopes in the 17th century. It was pretty clear they were atmospheric, not terrestrial features. Few writers posited adventures on a Jovian surface, he noted, although Jupiter played a somewhat significant role in the 1968 movie "2001: A Space Odyssey" and the accompanying book by Arthur C. Clarke.

"I'd be hard-pressed to think of any [film] that had the impact that ["2001: A Space Odyssey,"] did, that handled Jupiter as a real physical place," Krupp said.

The Pioneer and Voyager probes, and later the Galileo missions, journeyed to this giant planet, and changed human perspectives of Jupiter. More recently, the planet has become a sideshow to its moons.

"The real revelatory image was when the Voyager pictures had just appeared," Krupp said. "I was at this meeting, and they had been put out on the table. We had these prints just sitting there — Europa and Io in front of Jupiter. And in the three-dimensionality of the scene, they suddenly turned into worlds."

Prior to Voyager, nobody thought Jupiter's moons would be very dynamic, Krupp said.

"People thought, just more lumps of rock, like [Earth's] moon, fundamentally the same kind of thing," he said. "[Voyager] really altered once and forever the idea of what worlds in the solar system [are] really about."

Jupiter's moon Io was even the fictional site of a Hollywood film: the 1981 movie "Outland," starring Sean Connery, is a science-fiction version of the 1952 western "High Noon" and takes place on the Jovian satellite.

Real places

Beyond these two planets' fictional representations, though, science has wrought changes in the way people see and interact with Venus and Jupiter, Sutter said.

"For me, it was the growing realization that these planets are 'alive,'" he said. "They're not just static pictures; [they] change over human timescales. For example, [Jupiter's] Great Red Spot isn't as great as it was 100 years ago. The Venusian atmosphere has complex cycles that we're barely beginning to understand."

The biggest change is making planets into places in the public consciousness, Krupp said. Before Galileo, the planets were mystical objects, he said; now, humans can imagine standing on one.

"We see that they [have] landscapes; we imagine [them] in a far more personal way than was possible before," he said.

You can follow Space.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original story posted on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.