Rare Close Encounter of Venus & Jupiter Tonight Won't Happen Again Until 2065

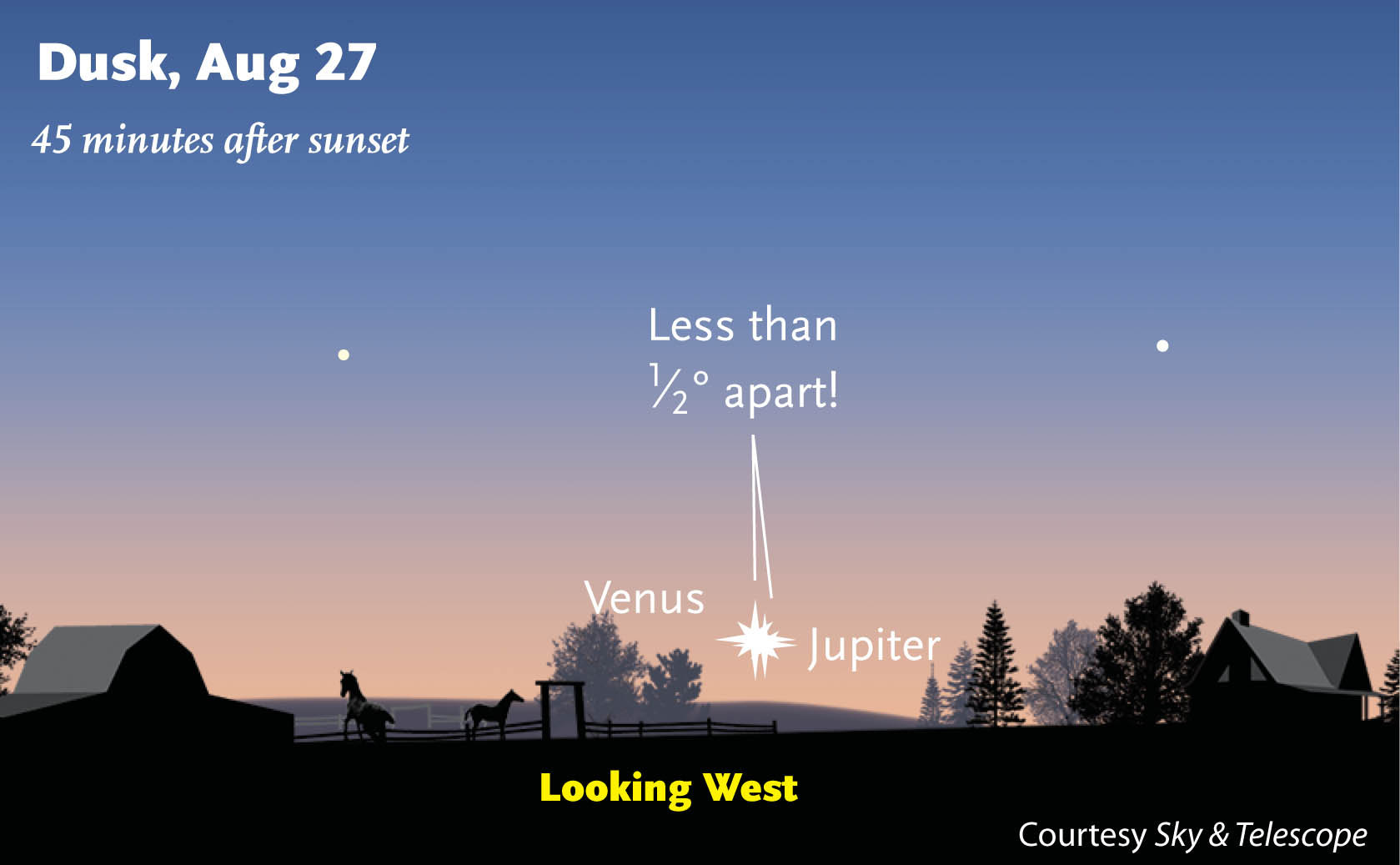

Tonight (Aug. 27), look toward the western horizon to see a rare celestial event and a parade of planets — no telescope required.

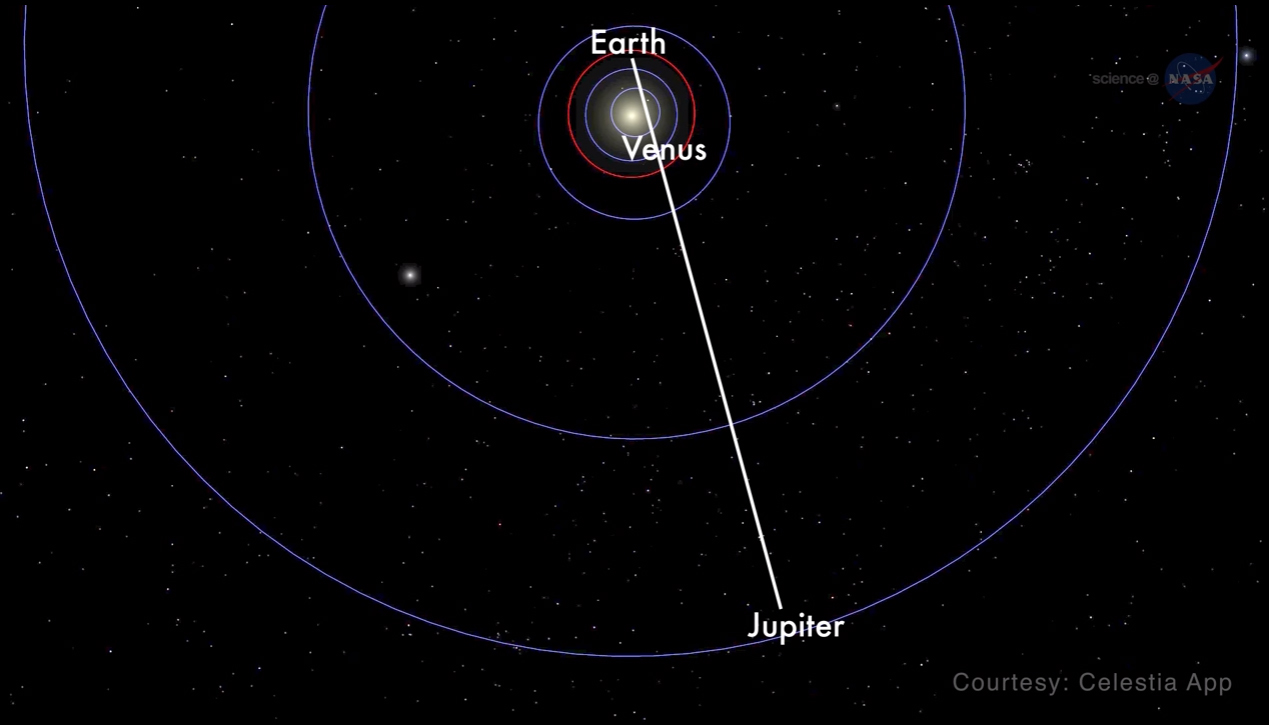

Just above the horizon, Venus and Jupiter will appear so close to each other that, from some locations, the two planets will almost seem to touch. The next time Venus and Jupiter will get this close will be in November 2065.

In addition to keeping a look out for this planetary conjunction, look higher up in the sky to see three other planets on parade: Saturn, Mercury and Mars. [Venus-Jupiter Conjunction 2016: When, Where and How to See It]

Where and when to see it

Viewers all over the globe should begin looking for the two planets shortly after sundown, just above the western horizon. Be sure to find a viewing location where the horizon is unobscured by buildings and trees.

For viewers in the northern U.S. and Canada, the planets will appear only about 5 degrees above the western horizon. A clenched fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees wide, so look for the two bright spots of light about a half a fist above the horizon.

Going south, the planets will appear higher and higher above the horizon: about 10 degrees from Florida, and about 20 degrees from Rio de Janeiro.

The best views of Venus and Jupiter will be from the East Coast of the United States and Canada. Unfortunately, the planets' closest approach will take place before sunset, at about 6 p.m. EDT (2200 GMT). But about 30 minutes after sundown, the light should fade enough to make the two planets (which will still be quite close together) visible to skywatchers. (The sight of these two bright planets apparently converging is so breathtaking that some people think it could explain the Star of Bethlehem story from the Bible.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At their absolute minimum, the two planets will be separated by 4 arc minutes, where 60 arc minutes equals 1 degree. To get a better idea of how to measure celestial distances, use the Big Dipper for reference: The middle star in the handle of the Dipper is called Mizar, while the faint star just above it is called Alcor. These two stars are separated by 12 arc minutes.

On the East Coast, some viewers may be able to catch the planets separated by as little as 5 arc minutes. On the West Coast of the U.S., the planets will be separated by between 6 and 12 arc minutes. Viewers in North and South America will see the planets grow farther apart as the night progresses.

Viewers in Europe will see the two planets moving closer together, and separated by 12 to 13 arc minutes.

Viewers in Japan, Australia and eastern Asia will see them appear on Sunday night (Aug. 28) local time, separated by about one half a degree (30 arc minutes) — which will still make for a gorgeous sight.

A special event

Venus and Jupiter will come so close together Saturday evening that they will create a special kind of conjunction called an appulse, when two objects approach each other so closely that they reach (or very nearly reach) the absolute minimum separation.

As a bonus, Venus will be nearly "full" — Earth's sister planet experiences phases, as the moon does, so it can occasionally appear as a crescent in the sky. But on Saturday, 93 percent of the planet will be illuminated, according to NASA.

Telescopes and binoculars are not required for skywatchers to see these five bright planets, but these aids can certainly enhance the experience. Venus and Jupiter will be close enough together to be visible in the same field of view in a telescope. If you live in a big city with lots of light pollution, consider making a trip to a darker location.

Editor's note: If you catch a photo of Venus and Jupiter's close encounter that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, you can send images and comments in to: spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter