Star Baby Boom Seen in Distant Galaxies

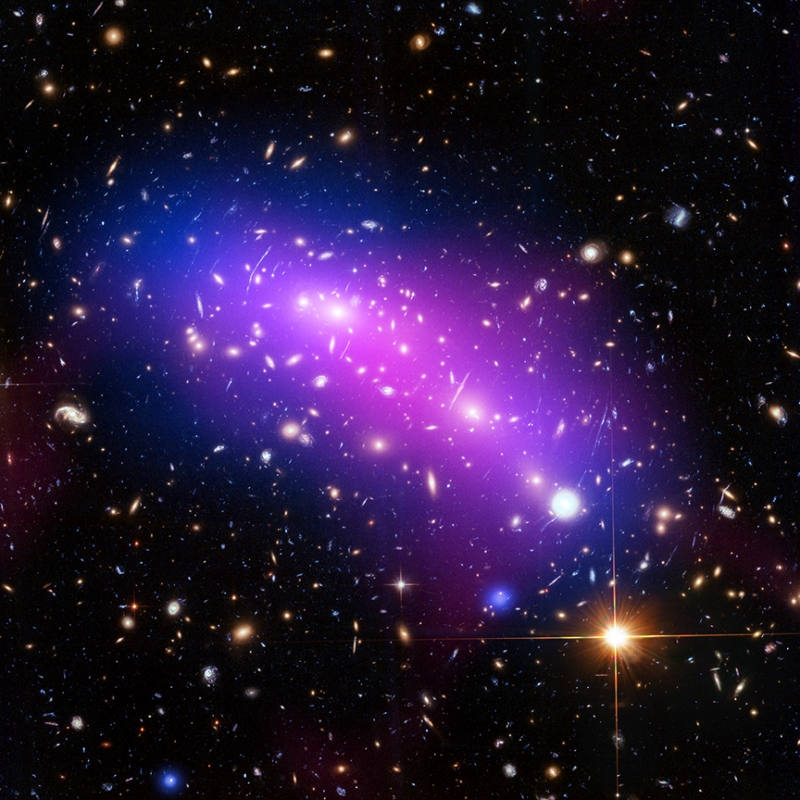

Some of the most distant clusters of galaxies ever discovered, which were born only 4 billion years after the universe was formed, are producing baby stars at higher rates than closer galaxy clusters, a new study finds.

The discovery suggests that something in the environment of clusters nearer to Earth is quenching star formation. In about 30 percent of the galaxies in distant clusters that should be forming stars, such formation isn't happening, the new study shows. In nearby clusters, the value is closer to 50 percent, according to a statement from the W.M. Keck Observatory, where some of the data for the new study was collected.

Astronomers said this newly discovered galaxy group is giving more information than ever before about when galaxy clusters slowed their star formation, early in the universe's history. Now, scientists want to know what's causing the discrepancy. [Keck Observatory: Cosmic Photos from Hawaii's Mauna Kea]

"While it had been fully expected that the percentage of cluster galaxies which had stopped forming stars would increase as the universe aged, this latest work quantifies the effect," Gillian Wilson, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Riverside, and an author on the new work, said in the statement.

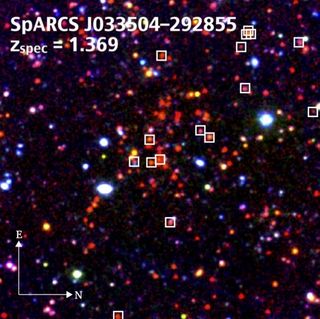

In addition to the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the clusters were found using data collected by the Very Large Telescope in Chile during the Spitzer Adaptation of the Red-sequence Cluster Survey, also known as SpARCS. The survey uses ground-based telescope observations in comparison with Spitzer space telescope data on distant clusters. SpARCS is led by the University of California, Riverside.

But what could be the cause of the vast difference in star-formation rates? There are multiple theories, according to the statement. A galaxy may be "starving" because the cluster environment is too hot for the galaxy to grab nearby cold gas and create new stars. Another theory is that nearby galaxies may "harass" others by interacting regularly at high speeds, which could pull material out of one galaxy.

"We looked at how the properties of galaxies in these clusters differed from galaxies found in more typical environments with fewer close neighbors," added lead author Julie Nantais, an assistant professor at the Andres Bello University in Chile.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It has long been known that when a galaxy falls into a cluster, interactions with other cluster galaxies and with hot gas accelerate the shutoff of its star formation relative to that of a similar galaxy in the field, in a process known as environmental quenching," Nantais said. "The SpARCS team has developed new techniques using Spitzer Space Telescope infrared observations to identify hundreds of previously undiscovered clusters of galaxies in the distant universe."

A study based on the research appeared in the August 2016 issue of the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.