Incoming! New Warning System Tracks Potentially Dangerous Asteroids

A new early warning system may help speed up calculations of when and where incoming asteroids could strike Earth.

By monitoring observations of newly reported space objects, a computer program called Scout can quickly identify potentially dangerous asteroids, then automatically call for follow-ups to calculate a more precise path for these bodies, researchers said.

"These are objects that observers have reported, and they suspect them to be asteroids," Paul Chodas, manager of NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object (NEO) Studies at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, told Space.com. "They are most likely asteroids, but they need to be confirmed by other observers." [Images: Potentially Dangerous Asteroids]

While midsize asteroids are frequently identified well before they hit Earth, smaller objects can be more difficult to spot and classify ahead of time. Correctly classifying these objects and determining their orbits takes multiple observations, researchers have said. And, especially for potentially hazardous impactors, the sooner the better, the researchers said.

Immediate follow-up

On Oct. 7, 2008, an 80-ton rock plowed through Earth's atmosphere and exploded above a remote area in Sudan. The asteroid, known as 2008 TC3, was spotted just 19 hours before it reached the African desert, making this the first incoming object tracked before crashing into Earth.

But the short notice provided little time for astronomers to follow up. With this in mind, NEO researcher Davide Farnocchia, also at JPL, worked to create a program to automatically monitor new observations and alert fellow astronomers.

"If Scout had been in observation eight years ago, it would have given early warning to observers that the asteroid — eventually named 2008 TC3 — should be followed up immediately because it had the possibility of hitting Earth," Chodas said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another object, which crashed into Earth's atmosphere around New Year's Day in 2014, wasn't identified until after it had already collided, burning up in the air over West Africa.

"Those two events made it clear what was needed and how necessary it was to automate [the process]," Chodas said.

When astronomers spotted a 10- to 30-foot (3 to 9 meters) space rock in November 2015, Scout took only 45 minutes to determine that the object would brush past Earth without colliding, Farnocchia said at a conference earlier this year. The asteroid buzzed past Earth a day after being discovered. In contrast, 2008 TC3 wasn't confirmed as an impactor until 12 hours before it hit Sudan.

Thanks to Scout, when astronomers spot a new object, "we will know sooner that it's a hazardous object," Chodas said.

Automated impact warnings

When an astronomer identifies an interesting object, he or she posts observations on a website hosted by the Minor Planet Center (MPC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Other astronomers can use that information to study the object, learning more about it and its orbit. But all of that takes time; astronomers need to check the DPS website regularly, and if the observations were posted from different time zones, researchers might not see new ones for several hours. For objects about to collide with Earth, those hours can be critical.

Scout automatically reviews the MPC's website. When a new object is posted, it takes Scout about 10 minutes to calculate the object's potential paths. If the newfound rock has the potential to threaten the planet, Scout alerts participating astronomers by email and text of the need for follow-up observations.

Observers around the globe can then head to their telescopes, track the object and post their own updated observations on the MPC's page. Scout continues to review the page, refining its calculations of the object's orbit and continuing to send messages as long as the rock remains potentially harmful.

"In many cases, after a few more observations, we realize it's not high priority, because it's not going to come as close as suspected," Chodas said. "That happens quite often."

The warning time for an impactor varies based on how large it is and how early it is observed, Chodas. Larger objects are brighter and more likely to be picked upearlier by asteroid-search programs, he said.

At 13 feet (4.1 m) wide, 2008 TC3 was small enough to escape notice until just before it exploded over Sudan.

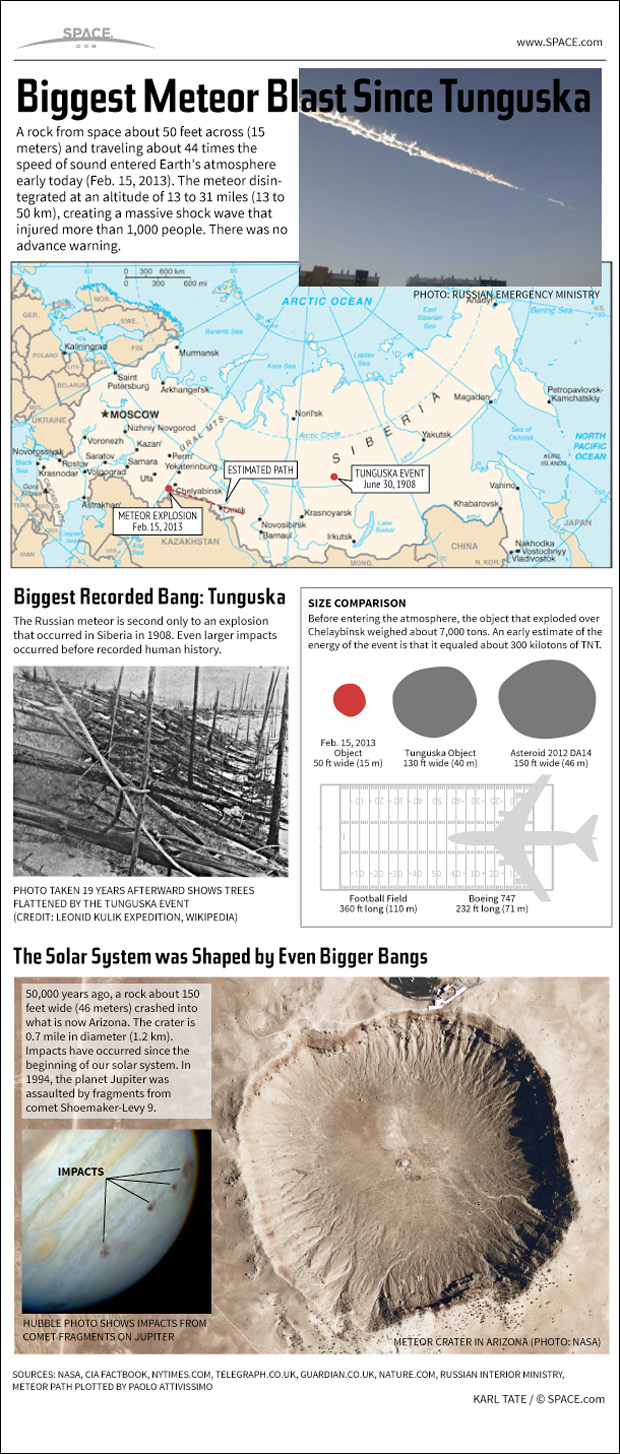

Some larger objects can escape notice if they follow certain paths through space. Scientists think the asteroid that exploded without warning over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February 2013, wounding more than 1,200 people, was about 65 feet (20 m) wide. The asteroid managed to avoid detection because it approached Earth from the sunward side and was therefore hidden by the sun's glare. [All You Need to Know About the Chelyabinsk Meteor Explosion (Video)]

Had the Chelyabinsk object been a bit larger, Chodas said, it could have potentially been detected months earlier, when it could have been seen on the nightside of Earth.

Chelyabinsk-size impactorsare rare, hitting Earth about once every 80 years or so, Chodas said. In contrast, smaller, 3-foot (1 m) objects come by fairly frequently, sometimes turning into bright fireballs as they burn up in Earth's atmosphere. Initial estimates of 2008 TC3 suggested that it had burned up completely, though these estimates were proven wrong as the asteroid rained down more than 600 chunks of rockinto the desert.

Scout tracks only objects whose status as asteroids has not yet been confirmed. Once the Minor Planet Center classifies a body as an asteroid, the object is moved to another page where it is monitored instead by a program called Sentry.

Sentry is a long-term impact-monitoring system that continues to track space objects. While Scout looks only about a month in the future, Sentry peers about a decade ahead. The newfound object should be confirmed and passed from Scout to Sentry fairly quickly, and the long-range program will then alert astronomers about future impacts, Chodas said.

"It doesn't get lost — none of the data gets lost," he said.

For pending impacts, NASA has contacts with the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency and other agencies to prepare for upcoming disasters.

"The key thing is to have a system that alerts us and alerts the observers," Chodas said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTReddor Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd