Europa Orbiter Could Sample Jovian Moon's Watery Plumes

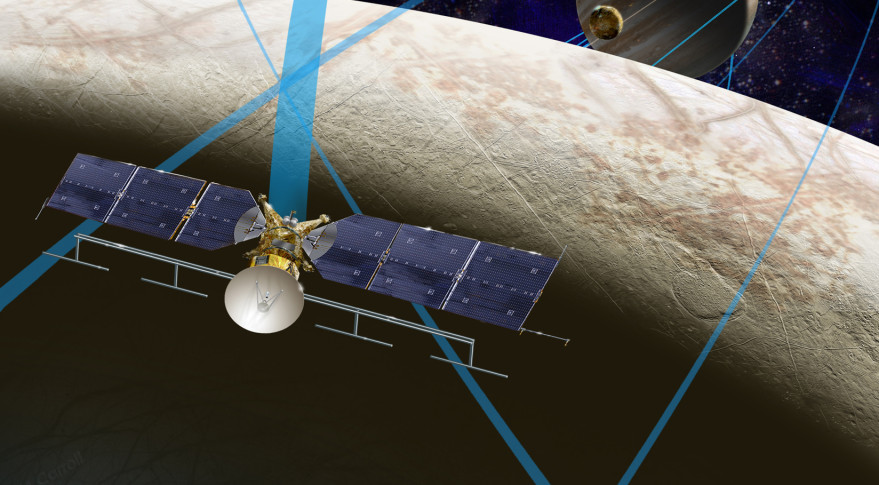

NASA's Europa orbiter mission, set to launch toward Jupiter's moon in the 2020s, would be able to collect samples of the icy plumes of water that might erupt from Europa's surface, mission scientists say.

Yesterday (Sept. 26), using Hubble Space Telescope observations, scientists announced the possible detection of icy water plumes erupting from the surface of Europa. Another study, in 2012, had reported the possible detection of plumes from Europa, but the findings of both studies are far from certain.

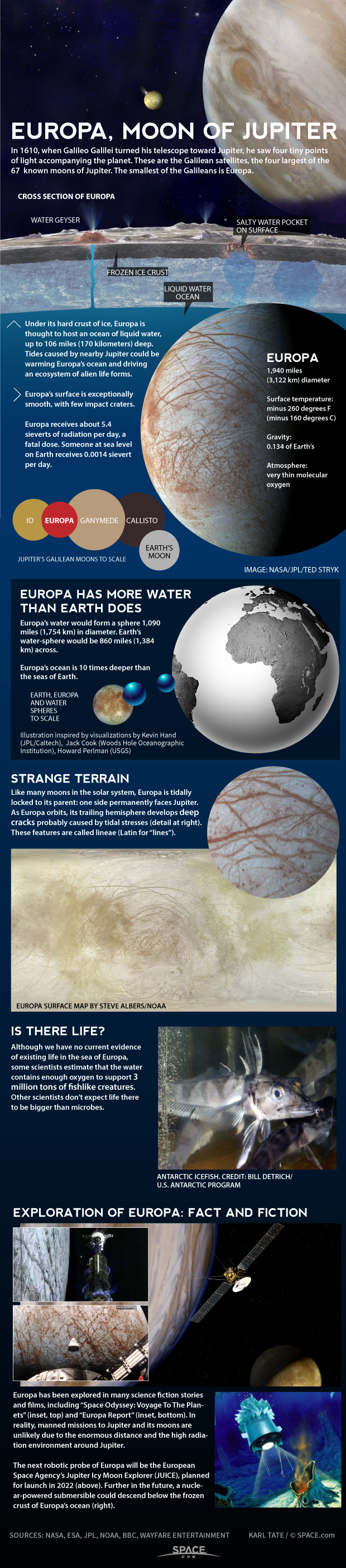

Europa harbors a liquid water ocean deep below its thick, icy crust, and scientists think it's possible that subsurface heat sources could create an environment fit for life. NASA's Europa mission will evaluate the moon's potential to host life. During a news conference yesterday, NASA scientists discussed whether the probe would be able to study the plumes and look for signs of life there. [Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's Icy Moon Revealed]

A hospitable world?

At first blush, Europa might not seem like a place that could support life. It's too far from the sun for liquid water to form on its surface, and it has a very thin, tenuous atmosphere. Its surface is also exposed to high levels of radiation from Jupiter.

But scientists think that, below its icy crust, Europa hosts an ocean, kept in liquid form by the addition of salts and perhaps due to internal geologic processes that generate heat. In fact, if those processes generate enough heat, it's possible that Europa could host the kind of life observed under ice sheets on Earth, or around hot water vents at the bottom of Earth's ocean.

"On Earth, life is found wherever there is energy, water and nutrients," Paul Hertz, director of NASA's Astrophysics Division, said at the news conference. "So we have a special interest in any place that possesses those characteristics. Europa might be such a place."

William Sparks is lead author of the study reporting the discovery of the plumes, and an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI). He called Europa "a truly compelling astrobiological target in the solar system."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If there are plumes emerging from Europa, it is significant, because it means we may be able to explore that ocean for organic chemicals, or even signs of life, without having to drill through unknown miles of ice," he said.

Although that may be a possibility in the far future, the upcoming mission to send a probe to orbit Europa (set to launch in the 2020s) was not designed to search for life, said Curt Nieber, a Europa program scientist for NASA. (This mission is officially unnamed but is unofficially called the "Europa Clipper.") Instead, the mission is designed to focus on determining whether Europa is habitable — that is, to confirm or deny those ideas about Europa's ocean being able to host life.

"We know how to measure habitability; we have a lot of experience with that," Nieber said. "We have a lot of instruments that are very robust and mature, and good at doing that. [But] when it comes to finding life, we don't have as much experience. And we actually have an ongoing and vigorous debate in the scientific community as to the best way of going about detecting life on a mission such as this."

Those debates will inform future missions to search for signs of life, perhaps on another icy moon or Mars, Nieber said.

Plume science

The scientists speaking at the news conference emphasized that there is still significant uncertainty associated with both these new observations and the 2012 findings that also reported evidence of plumes on Europa. Nieber said more information about the plumes is needed, either from current observatories or from the Europa orbiter itself, before specific plans will be made for the orbital mission to study the plumes.

"I think one of the biggest unknowns we have with these putative plumes is understanding their timing," Nieber said. "And I think the more observations we can get with Hubble and with [the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018], the better … we can construct a schedule for when we search for these plumes at close range with the Europa flyby mission."

But he also noted that the nine instruments currently selected for the mission can be used as a "very powerful plume hunter," although that is not the primary purpose of any of the instruments.

The instruments selected for the mission will be able to study Europa in ultraviolet, visible and infrared wavelengths. The new observations were taken in the ultraviolet, right at the edge of the range that the Hubble telescope can see, Sparks said. A wide range of wavelengths will make the instruments capable of looking for specific chemicals, such as water.

The instruments also will be able to see in what Nieber called "heat vision," meaning they will see the vents from which the plumes escape Europa's interior; those vents should be much warmer than the surrounding surface ice.

He said the mission team also considered the possibility of including a deployable probe on the Europa mission. This probe would disconnect from the primary probe to complete a unique mission, such as dropping down to the surface.

Nieber said the team decided that the science value of a deployable instrument was "not worth the risk.". With the nine instruments selected for the mission, "we feel we already have the ability to aggressively investigate those plumes," he added. [Water Plumes on Europa: The Discovery in Images]

Into the plume

A drop-down probe may not be necessary for the Europa mission to get its own sample of the material being spewed by one of these plumes. Built into the orbital plan for the mission is the ability to change course, so if scientists were to identify a plume and wanted to send the probe toward it, it would be possible to redirect the probe in about one or two weeks, Nieber said.

A fly-through of a plume would "certainly be a high priority for the Europa mission," he said. The instruments on board include compositional instruments that could "ingest samples of the plume material and analyze them," Nieber said. "[By] doing that, we can get an idea of what materials are inside the plumes and inside the dust and the ice particles," he added.

(Sparks noted that any life-forms that might survive under the surface of Europa would most likely be killed or destroyed in the plumes, due to the exposure to very cold temperatures and high radiation levels. So, even if the Europa mission were equipped to study life, the plumes would only contain remnants of life that would have to be analyzed.)

NASA's Cassini probe, which is studying the Saturn system, has flown through the active plumes on Saturn's icy moon Enceladus.

These fly-throughs have "revealed a tremendous amount of information about the ocean that is present beneath Enceladus' ice shelf, and we would kill to have that kind of information and data for Europa," Nieber said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter