Europe succeeded in placing a methane-sniffing spacecraft in orbit around Mars today (Oct. 19), but it's still unclear if that probe's piggyback lander made it safely down to the planet's surface as planned.

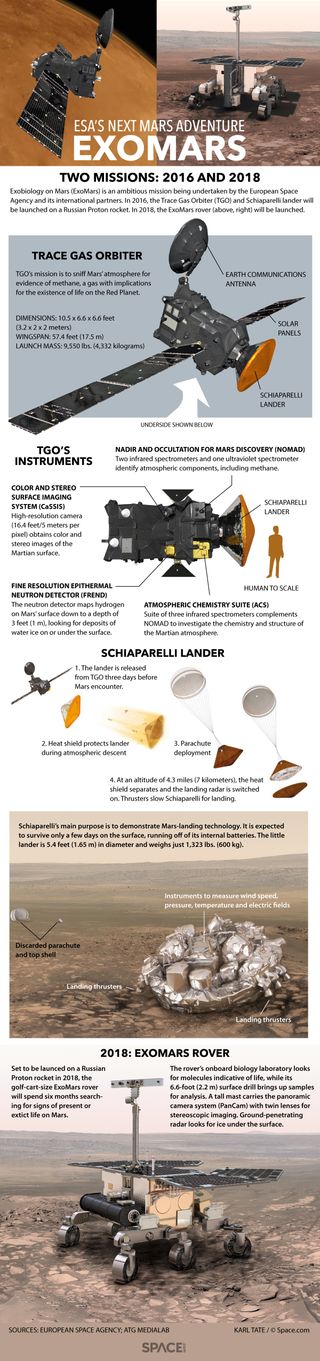

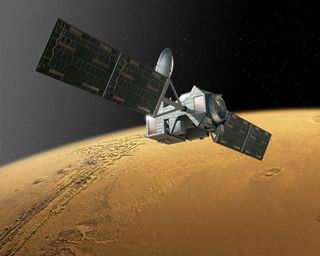

The Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), part of the European-Russian ExoMars 2016 mission, slipped into orbit around the Red Planet late this morning after completing a crucial engine burn, European Space Agency (ESA) officials said.

"It's all good," ExoMars Flight Operations Director Michel Denis said at a news conference this afternoon. "It's a good spacecraft at the right place, and we have a mission around Mars." [Europe's ExoMars 2016 Landing: Complete Coverage]

But that's just half of the story.

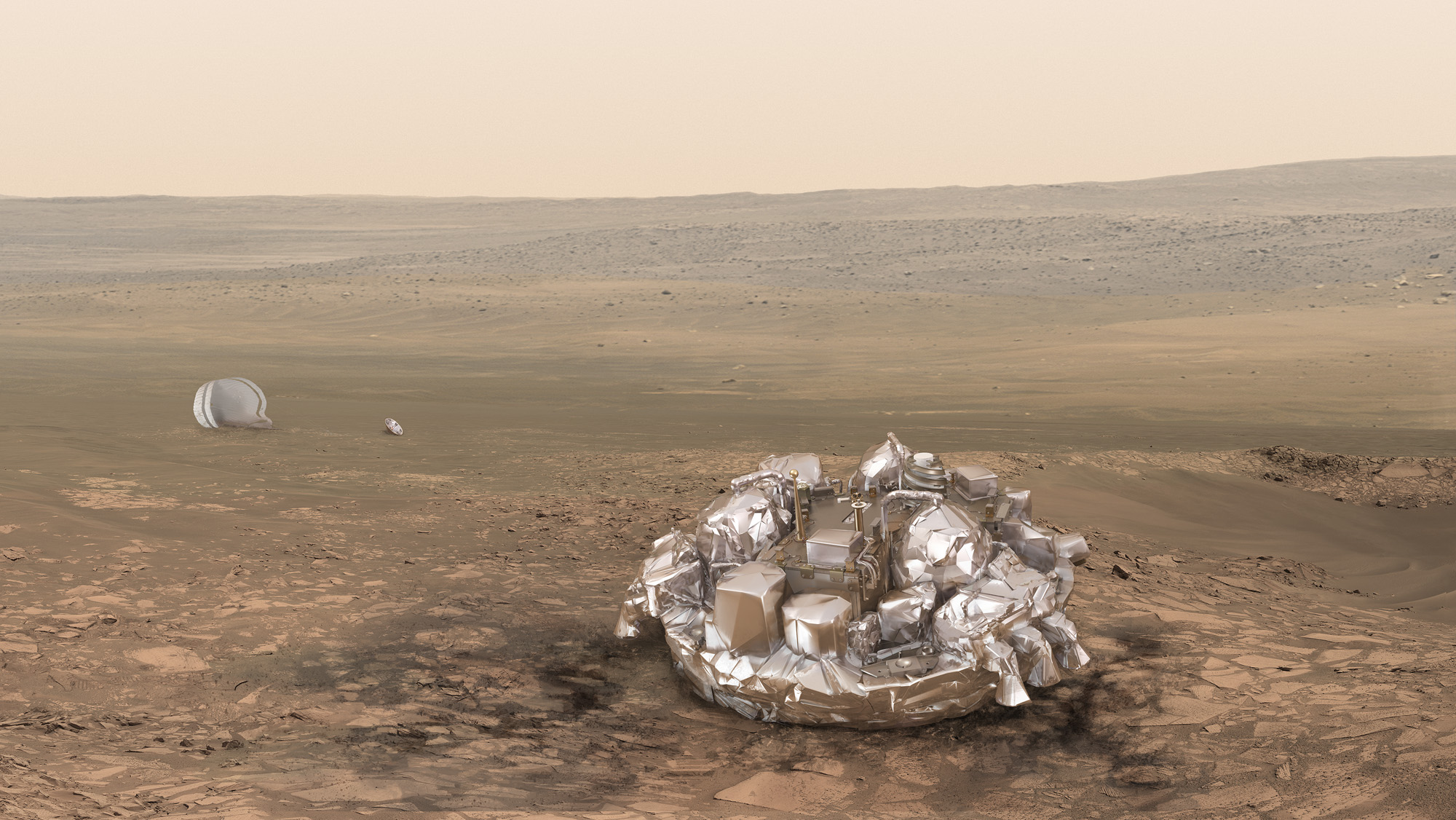

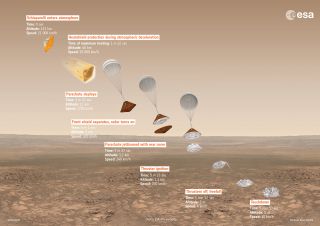

ExoMars 2016's lander, called Schiaparelli, hit the Martian atmosphere as expected at 10:42 a.m. EDT (1442 GMT); however, mission team members are still waiting for a signal to confirm that the craft survived its touchdown six minutes later.

Schiaparelli's signal came in loud and clear as the lander streaked through the Martian atmosphere but stopped shortly before the lander was scheduled to hit the ground, said Paolo Ferri, head of ESA's mission operations department.

"It's clear that these are not good signs, but we will need more information, and that's what's going to happen tonight," Ferri said. "I'm quite confident that tomorrow morning we will know" what happened, he added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If Schiaparelli did stick its landing, the maneuver would mark the first fully successful Mars touchdown by Europe or Russia — by any entity other than NASA, as a matter of fact.

Tag-teaming Mars

Schiaparelli and TGO launched together in March, lifting off atop a Russian Proton rocket from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

The two spacecraft represent the first phase of the two-part ExoMars program, which is led by ESA with Russia's space agency, Roscosmos, as chief partner. The second phase of ExoMars will launch a life-hunting rover in 2020, if all goes according to plan.

Europe is spending 1.3 billion euros ($1.43 billion at current exchange rates) on the ExoMars program, ESA officials have said.

Schiaparelli and TGO traveled together until Sunday (Oct. 16), when they separated ahead of their divergent Mars arrivals.

Schiaparelli reached the Red Planet first, hitting the thin Martian atmosphere at the blistering speed of 13,050 mph (21,000 km/h). Mission team members tracked the lander's progress this far, but they weren't able follow it all the way down to the surface.

"Initial signals [from Schiaparelli] were received via the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) as Schiaparelli descended to the surface of Mars, but no signal indicating touchdown yet," ESA officials wrote in a blog post this morning, referring to an array of dishes near Pune, India.

"This is not unexpected due to the very faint nature of the signal received at GMRT," they added. "A clearer assessment of the situation will come when ESA's Mars Express [orbiter] will have relayed the recording of Schiaparelli's entry, descent and landing."

But the data from Mars Express — which has been circling the Red Planet since 2003 — were inconclusive, ESA officials later said, so Schiaparelli's fate remains uncertain. The situation should clear up by tomorrow, after mission team members have had more time to search for signals coming from the lander using GMRT, Mars Express and two other orbiters — NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) spacecraft.

Schiaparelli came down in the Meridiani Planum, a highland region just south of the Martian equator. NASA's Opportunity rover touched down in Meridiani Planum back in January 2004 and is still going strong today.

But Schiaparelli won't come close to Opportunity's longevity, even if the probe survived today's touchdown intact: The ExoMars 2016 lander is powered by nonrechargeable batteries that should die in just a few days, ESA officials have said. That's because Schiaparelli is a landing demonstrator whose primary purpose is proving out technology required to get the ExoMars 2020 rover down on Mars safely.

The data Schiaparelli gathers would therefore be limited. The lander does feature a meteorological station to measure temperature, wind speed, humidity and other weather conditions on the Martian surface. Schiaparelli also was programmed to do some science work during its brief descent through the planet's atmosphere — for example, measuring air density, pressure and temperature from an altitude of 81 miles (130 km) down to the planet's surface, ESA officials said.

The plan also called for Schiaparelli to capture 15 black-and-white images as it fell. The lander's camera was not designed to take photos from the surface. [How Europe's ExoMars Missions Work (Infographic)]

Searching for signs of life

But TGO did its job, and the probe settled into a highly elliptical orbit around the Red Planet at 11:24 a.m. EDT (1524 GMT), ESA officials said. TGO's current four-day orbital path takes the spacecraft as close as 186 miles (300 km) to Mars and as far away as 60,000 miles (96,000 km), if the mission team's pre-arrival calculations reflect reality.

But TGO won't stay in this orbit forever. In March 2017, the spacecraft will begin a yearlong "aerobraking" campaign, shifting into a circular, 250-mile-high (400 km) orbit by zipping through the Martian atmosphere at high altitudes. (This will create drag that slows TGO and lowers its orbit.)

By March 2018, TGO should be ready to start its science mission, which involves searching the Martian atmosphere for methane and other gases that could be signs of alien life. (While methane can be produced by geological processes, the vast majority of the methane in Earth's atmosphere was generated by living organisms.)

TGO will also hunt for deposits of water ice on or just below the Martian surface and serve as a communications relay for Opportunity, NASA's Curiosity rover and the ExoMars 2020 rover, ESA officials have said. TGO's mission is scheduled to end in December 2022.

Exploring Mars

The arrival of TGO brings the tally of active spacecraft at Mars up to eight. Two of them are surface craft — Opportunity and Curiosity — while the other six are orbiters: NASA's Mars Odyssey, MRO and MAVEN; Mars Express; India's Mars Orbiter Mission; and TGO.

Schiaparelli could still be added to this list, though its inclusion would last just a few days (until its batteries run out). And more robotic explorers are headed to the Red Planet in the near future. NASA plans to launch a lander called InSight in 2018, to probe the interior structure of Mars. And two life-hunting rovers should follow in 2020: the ExoMars vehicle and NASA's 2020 Mars rover.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.