How 'Hidden Figures' Came Together: Interview with Author Margot Shetterly

Growing up in Hampton, Virginia, author Margot Shetterly took for granted that scientists and mathematicians would as often as not be female and nonwhite. But after leaving the town, home to NASA's Langley Research Center, where her father worked, she realized that was far from the case.

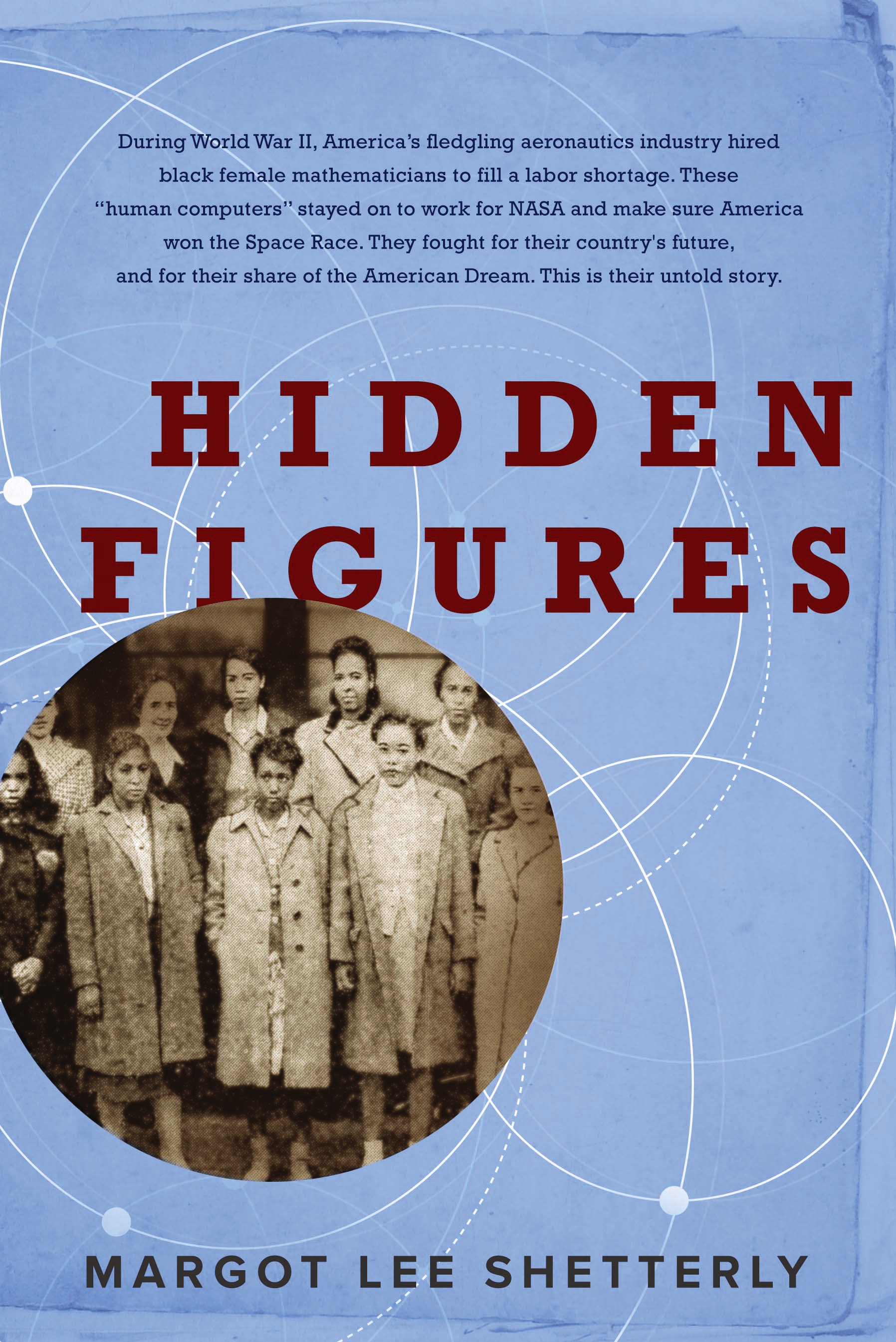

Shetterly's new book, "Hidden Figures" (William Morrow, 2016) follows the black women at Langley who were first hired during World War II as "computers," scratching out complex computations for the center's aeronautical and rocket research before the days of electronic computing. In those days, it was known as Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory, and it was run by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). As the years passed and the center evolved, the West Wing Computers — the East Wing consisted of white women — became engineers, (electronic) computer programmers, the first black managers at Langley and trajectory whizzes whose work propelled the first American, John Glenn, into orbit in 1962.

The book focuses on Katherine Johnson, a brilliant mathematician who famously double-checked the calculations for Glenn's launch trajectory (and for whom a Langley research facility was recently named), and three other women whose lives and work tie together the history of spaceflight, civil rights and the evolution of the American dream — all in one little Virginia city. [On the Set of "Hidden Figures": 2017 Movie Based on the Book]

Space.com talked with Shetterly about her new book, the challenges of uncovering that history and why human computers are suddenly looming large in the public consciousness.

Space.com: Was it challenging to track down the history of Langley's woman computers?

Margot Shetterly: One [challenge] was trying to figure out exactly how the segregated group of black women came to Langley. Really trying to track down when it happened, who was there, where they were originally sent to work, because they had to be in a segregated office.

At the end of the day, what I concluded is that it was — not quite a handshake deal, but that everyone kind of quietly agreed this was going to happen, and it happened. It wasn't like something that happens with a lot of fanfare. Tracking that down, it was really like — there's an article in the black newspaper The [Norfolk] Journal and Guide, which announced the first woman going there, and then all of a sudden their names started appearing in the Langley newsletter.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: How did you choose which women to focus on for your narrative?

Shetterly: You couldn't tell this as a single person's story. This is the story of broad success of women overall, and African-American women specifically, in a job category that it's simply assumed where they don't exist. During a time of Jim Crow segregation, during a time when women frequently weren't even allowed to have credit cards in their own names, here were these women — large numbers of women — doing very high-level mathematical work at one of the highest scientific institutions in the world at that time. I wanted it to be a story that could show that broad group, but at the same time, in order to make it interesting, to make it a story as opposed to a history textbook, you have to choose the people with the most compelling stories.

Space.com: So whom did you follow?

Shetterly: Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson and Christine Darden — each of them represented a certain slice of the narrative in terms of the development of women in the workplace over that time. They each faced different things along the way.

They all had different kinds of work; we were able to look at both the aeronautical work and the space work that the center was doing, and they all had different connections to the larger world … Dorothy Vaughan, who was the first black supervisor at what became NASA by being made a section head of the segregated group of black women, had also worked as a teacher at one of the high schools that became a fundamental part of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case. Here's this woman, she's connected to two of the most amazing parts of the 20th Century. [Engineer] Mary Jackson was from Hampton and had this family history that really came out of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Each of the women, in addition to the work they did and in addition to the compelling personal stories, ended their careers at the research center, so I was able to follow them out to the end of their careers.

They also had some significant links to the larger world: The idea that Katherine Johnson worked in the antique shop at The Greenbriar, which is this old war emblem, the luxury bomb shelter for Congress — I just couldn't believe it.

Space.com: Can you talk about how you incorporated scientific details into the story?

Shetterly: I'm not a scientist or a mathematician. So it really did take a lot of self-study and reading research reports and reading textbooks and looking at videos on YouTube, which were very helpful, to put together the work that the people did. I think I have to have a greater level of technical command of the topics than what actually made it into the book … This is a book for the general audience, and most general readers are probably not that interested in Reynolds numbers or differential equations.

At the same time, there were other parts — for example, really understanding what they were doing with the wind tunnels and what makes things fly. It's interesting, because you're asking yourself this question that you take for granted. You get on a plane, it moves through the air, it lands safely, you don't think about it. And so having to actually slow down and think about the physics and the math and the understanding of the concept behind it was really enjoyable, and I learned lot. Even though I would certainly not call this a technical book, I've enjoyed talking with lots of the ex-NASA people about this stuff — but it had to be put into a form that the general reader wouldn't get stumped or just put the book down because they thought it was too much.

Space.com: Was your research and writing process more one of writing as much as possible and editing things out, then?

Shetterly: I wrote so many drafts of this book. I think that a lot of the early drafts were really a way for me to suss out what really happened. There were so many things that I needed to understand; the kind of work that was done at Langley, the kind of research — I spent a lot of time going through the NASA technical report server. Just an amazing gift. Taxpayer dollars so well spent that anyone with a computer can go into the database and they can find the research reports from NASA and the NACA going back to the founding of the agency. You can literally see the progression of aeronautical research and development from the 1920s until today. It is remarkable. There were so many great resources that allowed me to put too much meat on the bones and then carve back so that what was always leading was the women and their stories and their perspective, with the history and the science being pulled by their stories.

My obligation as a writer is to try and uncover all of the aspects of the history, and put all of those things in the footnotes and make sure everything is really documented. That was something that was also really important to me from the very beginning: not just writing the story, but making sure that I had left as much as possible a comprehensive trail of breadcrumbs of where to find this information. There were a lot of times when I'd dig into boxes at the National Archive and instead of those lovely preserving archive boxes it'd be some cardboard box that had obviously gotten wet and nobody had looked at the papers since they'd got thrown in there in 1946 or something. My publisher has given me permission to publish notes and make them available on my website, and so I'm trying to figure out when I can actually get that done. If there are other people who are interested in this history who want to use those resources, that would just be incredible to me. [Best Spaceflight and Space History Books]

Space.com: What do you hope people get out of this book?

Shetterly: I really hope that this goes a long way to helping all of us change our perception about what a scientist looks like, what a mathematician looks like, who's capable of doing that work at the highest level. This is a discussion that we're having at a very high level and across many different disciplines: education, and the private sector and government. How do we fill the need for technology workers, people who have computer skills and math and science skills? How do we get a more diverse science workforce? These are all issues — I would look at these documents that were from the 50s and 60s and 70s, and you'd swear they were written two weeks ago, because the issues are the same.

And the other thing is, even though it's a story that's being told from the point of view of African-American women, I hope people see this as really a very American story. It's the space race, it's the Cold War, it's the women's movement, the civil rights movement, World War II — all of these grand, sweeping changes and upheavals and forces that defined the 20th century that we've all studied in school and we all still talk about, and we're all still fighting about in a lot of ways, and it's attached to this group of African-American women. So just because the protagonist is different, doesn't mean that it's less of a capital-H American History.

I do believe that it is possible to see this as a great, sweeping American epic, which is one of my favorite things.

Space.com: Why are there so many stories about early NASA computers coming out right now?

Shetterly: That is a great question. I don't know why. Perhaps it is because a lot of these women are from the World War II generation and they are passing away. People are interested in capturing these stories before it really is too late … I think perhaps it's because there's an urgency to collect the stories of people from this generation. And I think also it's because this whole thing of women in STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics], and minorities in STEM, is so top-of-mind right now.

Here are lots of examples over history of women working as mathematicians and really providing the raw calculations that allowed us to fuel stupendous growth in technology and scientific knowledge. A lot of this came out of the needs of World War II, then the Cold War, then the space race — does it take a national emergency for us to tap into all of the talent? Is there a way to do it without precipitating a national emergency? I don't know. ['Rise of the Rocket Girls' (US 2016): Book Excerpt]

Space.com: Are you considering any follow-up book on this part of NASA history?

Shetterly: I actually have two book ideas that came out of this that don't have to do with space, but that sort of — I kind of see this as a midcentury African-American trilogy. They came from the same period of time and ask a lot of similar questions about social mobility and work.

But I do think that there are — you could probably write more books just on the Langley research center. I was surprised how little I knew about the significant contributions to aviation that had happened right there in Hampton, Virginia. Now every single time I get on a plane and see the delta swept-back wings, and I see the winglets, and I see the upright tail, I'm looking at all these things and I'm seeing the research reports in which those ideas were hatched. And that story — we know about the Wright brothers, but there were a lot of fascinating, larger-than-life personalities that helped build airplanes, the aeronautics industry, which we all take for granted today.

I think there could be another 50 books, and each one would be absolutely fascinating.

This interview has been edited for length.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.