For NASA's Hubble Successor, Failure Isn't an Option

Lee Feinberg came to NASA in 1991 as a young optical engineer on the first Hubble repair mission. His first task was to hire a company to fix the deformities in the glass telescope, a problem that led to a repair visit by astronauts and a major headache for administrators on the ground.

"The feeling we had was that NASA's credibility was at stake with the Hubble repair mission," said Feinberg. "We knew that failure was not an option. We worked incredibly hard to get it right."

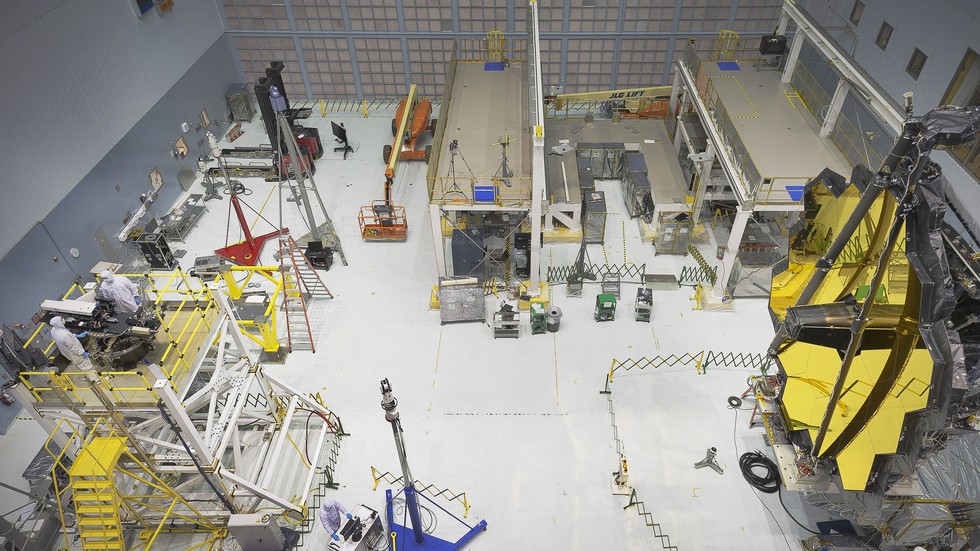

Today Feinberg is the optical telescope manager for the James Webb Space Telescope, an $8.7 billion instrument that was assembled for the first time this week at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

The launch isn't until October 2018, but there's one big difference between Hubble and Webb. For Webb, there will be no dramatic rescue mission. The space telescope will be parked at the L2 point, which is a million miles away from Earth. So the pressure is on at Goddard and its contractors to make sure the Webb doesn't end up like Hubble. NASA engineers will fold up the entire instrument into the cargo bay of a French Ariane rocket, send it aloft, then after reaching its parking spot, unfurl its tennis court-sized solar umbrella to protect the delicate instruments.

Everything has got to work perfectly — no goofs allowed this time.

RELATED: Covers Off! Say Hello to Our Future Mega-Space Telescope

"I'm getting that same passion, the same long hours and teamwork, that's what I'm feeling on Webb," Feinberg said. "That's what it's going to take to build something this sophisticated and send it to L2."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Feinberg wrote a research paper on the failures of the Hubble, which was also built at Goddard. He said that managers at the time didn't rely on outside reviewers to double-check their work.

NASA managers on Hubble "ignored the second instrument, but the data was staring them in the face. (Today) we have test criteria and an independent team and peer reviews of the data. It assures ourselves that if there are issues we review them."

The Webb telescope will be bigger and better than Hubble by more than tenfold, according to NASA, with seven times more light collecting surface.

By capturing images of infrared light that is farther away (and therefore longer ago in time) than visible light, it will be able to see objects that formed just after the Big Bang.

It will also be able to zoom in on the planets orbiting stars, such as the possible "Earth-like" exoplanet discovered recently around neighboring Proxima Centauri.

"We would like to know how did we get here from the Big Bang," said John Mather, science director for the Webb. "First stars and galaxies came and we have supercomputer simulations, but we don't know how. So you have to go and look. Astronomy has always been an observational science."

Mather said the Webb telescope will "look at everything from Mars outward."

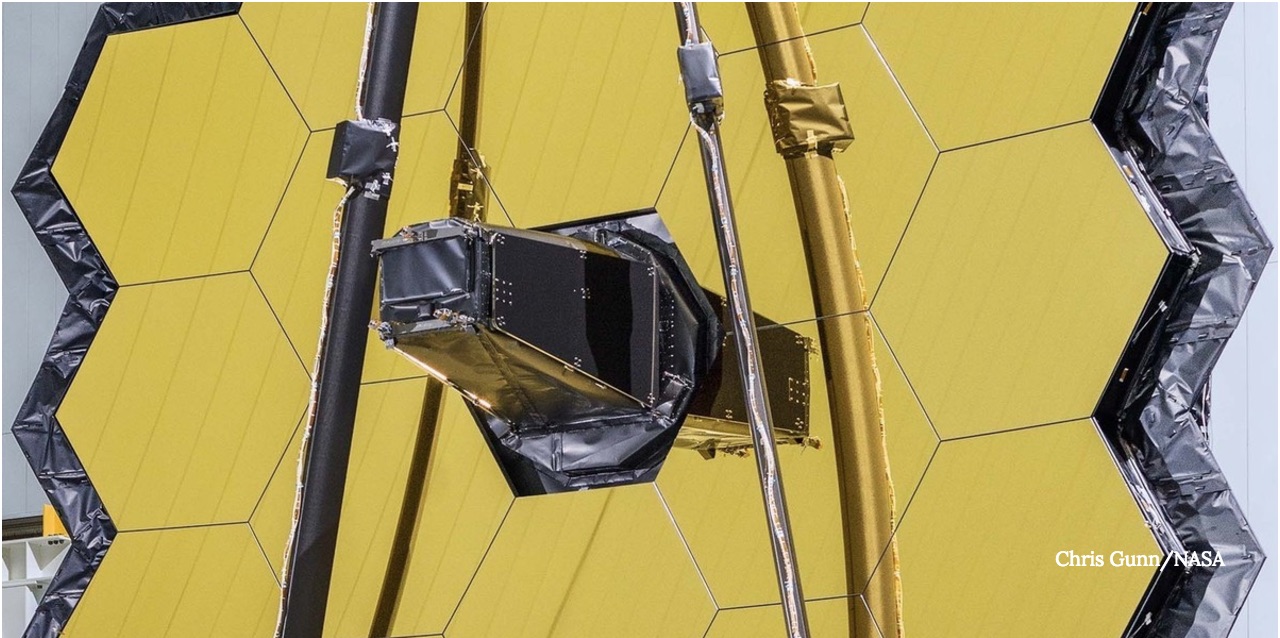

The Webb is an engineering marvel composed of 18 hexagonal mirrors that can adjust themselves to form a smooth collecting surface. The mirrors are covered in thin layers of gold and beryllium to reflect and collect certain wavelengths of infrared light.

Inside the huge clean room at Goddard, the Webb telescope looks like a gold-plated Pilgrim's hat tipped on its side. Now that the telescope is assembled, it will begin several months of shake, vibration and acoustic testing at Goddard to make sure it can handle the rigors of its launch from French Guiana.

RELATED: Sunny Side Up: James Webb Telescope Passes Sunshield Tests

In February 2017, it will head to a giant freeze chamber at the Johnson Space Center where it will be cooled down to 50 degrees kelvin for more tests. Researchers like Feinberg want to know if Webb can operate at those outer space temperatures and still collect data that hundreds of astronomers and astrophysicists are drooling to get their hands on.

Mather and other NASA officials gathered at Goddard on Wednesday to showcase the telescope. He said that the Webb is likely to be the last space telescope that won't be assembled in space in modular pieces.

If something goes wrong on Webb, there's not even a grappling ring for an astronaut to grab onto.

"We don't want to mess with this one. It is a really cold telescope. The solar panels to protect the telescope have sharp edges and astronauts don't like being around sharp edges."

Mather echoed Feinberg's lesson from Hubble. "If you really care something about something you have to measure it twice," he said. "We built our entire program around that."

Even though the Webb telescope has gone through a period of cost overruns during the first several years of construction, NASA administrator Charles Bolden said that it's been on budget and on time for the past six years. He said that he doesn't believe a new president would cancel it.

PHOTOS: NASA's Next-Generation Telescope: Ace Comet Hunter?

"We think we have an incredibly good story to tell," Bolden said. "The James Webb Space Telescope has stood the test of time. We spent a tremendous amount of money up front. Most was spent making technology that did not exist when this telescope was conceived."

Bolden was one of the astronauts that originally deployed Hubble in the early 1990s. He's led the agency since 2009, but he's not likely to remain at NASA by the time the Webb telescope launches in 2018.

For the engineers on the team, the next two years will be nerve-wracking, but also exciting.

"Things are going smooth at this point because we've done so much preparation. But we have to execute," Feinberg said. "At the end of the day, if you have a really good test program, you feel confident. You don't want to be sitting there when you are ready to launch this thing that you have any regrets."

Originally published on Seeker.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Eric Niiler is a science and climate reporter at The Wall Street Journal, as well as a writing lecturer at Johns Hopkins Advanced Academic Programs and a contributor to many other places such as National Geographic, the Washington Post, and more. He also has an interest in artificial intelligence and its applications in scientific and medical research. Eric has a master's degree in Science and Medical Journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor's degree in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.