Harvard's 'Computers': The Women Who Measured the Stars

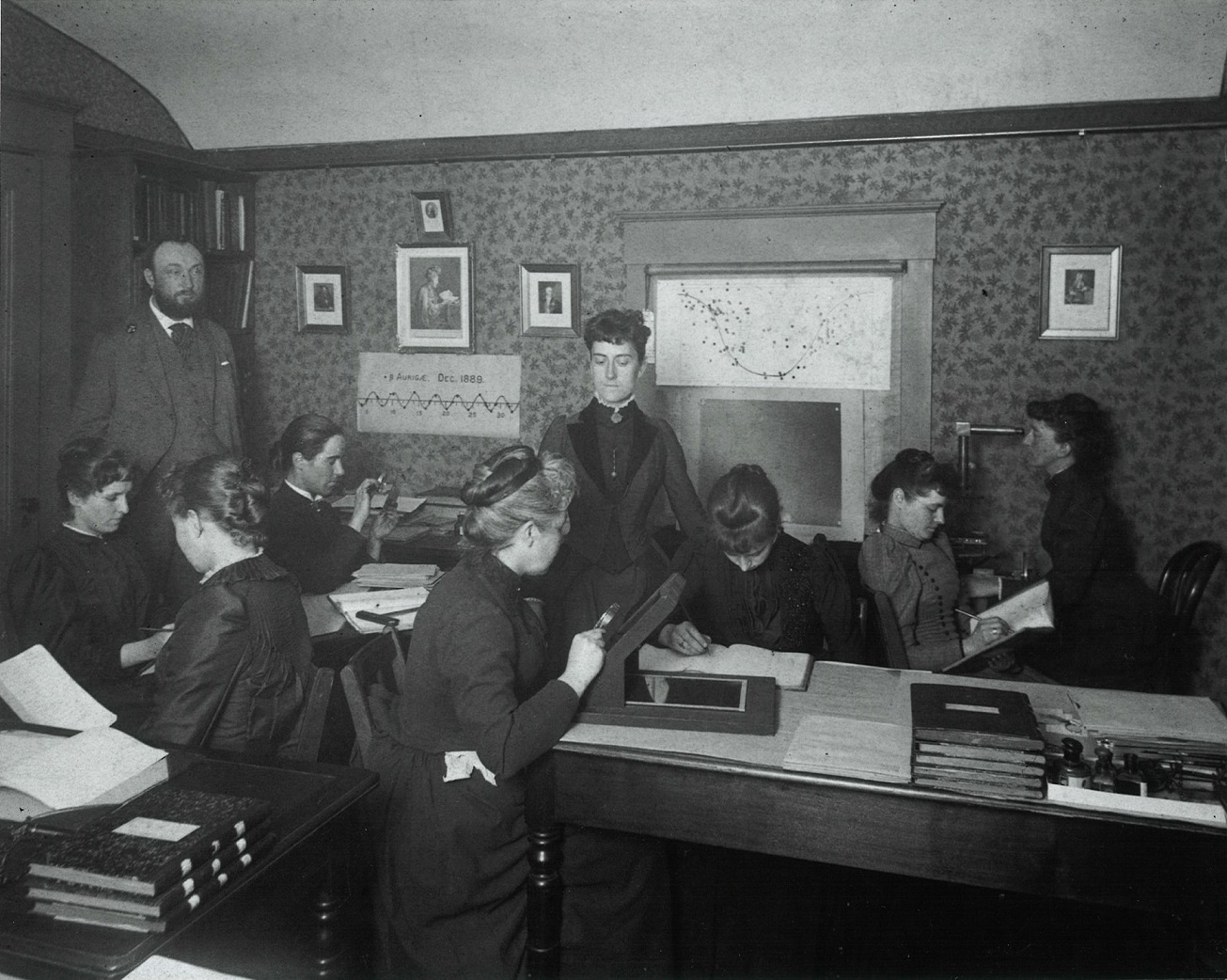

Before modern devices such as laptops and mobile phones were invented, a "computer" was a person who did calculations. At the Harvard College Observatory, between the late 19th century and early 20thcentury, several dozen women were "computers" who helped lay out some of the fundamental assumptions of astronomy.

Their job was to look over photographic plates of the night sky and compare the positions of stars between one plate and another. The computers were mainly hired by Edward Charles Pickering, who was director of the observatory from 1877 to 1918. According to Smithsonian magazine, Pickering expanded astrophotography shortly after the new plate technology was made easily available. He was initially caught short, however, when the number of plates produced exceeded the number of people he had on staff to analyze the images.

Because looking at plates for hours on end was considered boring and unspecialized work, Pickering turned to women to perform the duties. At the time, women were rarely employed outside of the home and were believed to be best suited to managing households. While Pickering's employment was a jump forward for these women, they remained mainly in clerical roles – showing that women's status in astronomy had a long way to go in the early 20th century.

Tough work

Harvard's first female computers began work around 1875, although the date is not fixed precisely in a timeline from Harvard's photographic plate website. "Before then, women, like Eliza Quincy, daughter of founder Josiah Quincy, were only given volunteer status as observers, though several women had applied to work as student assistants," Harvard wrote. "The first women computers hired [were] R.T. Rogers, R.G. Saunders and Anna Winlock."

The women worked full days for six days a week, being paid between 25 cents and 50 cents an hour. This was far less than what a man would have been paid, and in some cases the women hired were not specialists in astronomy. All told, a few dozen women (reported as anywhere between 40 and 80) were hired over the decades and were informally known as "Pickering's Harem" – a term that today would be considered derogatory.

In other ways, however, Pickering helped to pioneer modern astronomy. At the time, most observations were done mainly by humans looking through telescopes. Pickering, the Smithsonian wrote, believed that the human eye would get tired over time and may not make accurate measurements. Photographs would provide the opportunity to look at swatches of the sky repeatedly, and could help establish such fundamentals such as which stars were brighter than other ones.

One of the first computers was Pickering's maid (and a former teacher), according to the American Museum of Natural History. Williamina Fleming is today best known for finding the Horsehead Nebula and also for classifying the stars depending on their temperature. Thanks to her, the first Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra was published in 1890 showing the brightness, star type and position of more than 10,000 stars, according to Harvard.

Some of the women were specialists, however, such as Annie Jump Cannon. She had a college background in physics and astronomy. Among her contributions was creating the stellar classification system still used today. From hottest to coolest types of stars, the system uses seven letters to organize stars into groups: O, B, A, F, G, K, M. The sun is considered a G star, while M stars are considered red dwarfs and O stars considered blue giants. Cannon created a phrase to make the system easy to remember: "Oh! Be A Fine Girl – Kiss Me!"

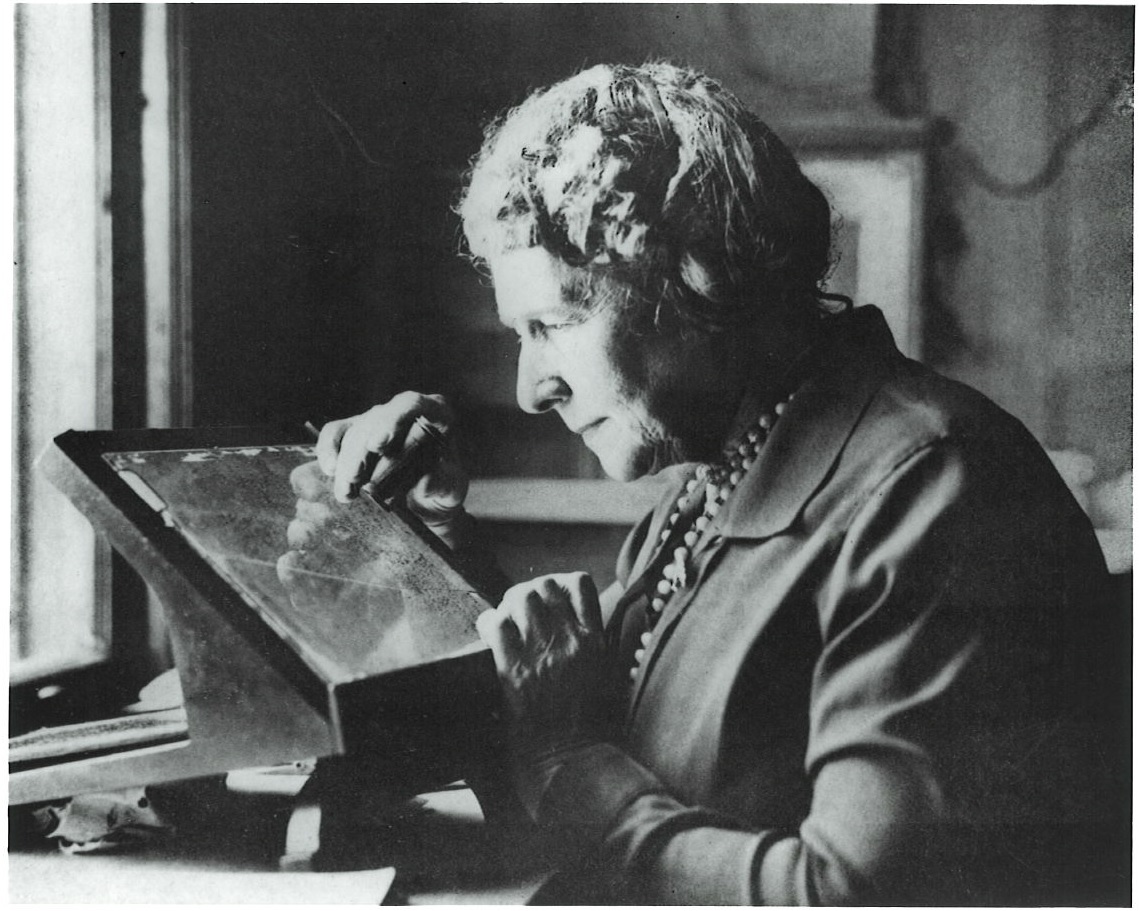

Henrietta Swan Leavitt also had studied astronomy at Harvard, and was hired in 1907 to look at variable stars. According to Harvard, she commonly would place one photographic plate on top of another to see how the brightness in certain stars changed between exposures. She found roughly 2,400 variable stars, and also discovered Cepheid variables. These are stars that have a consistent luminosity, which makes them handy "measuring sticks" to figure out the universe's expanse.

Legacy of the Harvard computers

Leavitt's use of Cepheid variables ended up being highly useful for Edwin Hubble, who used them in 1924 to establish that the Andromeda Galaxy (more officially known as M31) is actually a galaxy of its own some 2.5 million light-years outside of the Milky Way. Five years later, he published work showing that the universe is expanding, based in part on observations that certain stars were "redshifting" (moving farther away from us, which stretches their light spectrum closer to red.)

Although not a "computer," Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved a noteworthy feat in 1925: she was the first person to get a doctorate in astronomy from Harvard, although her degree was officially issued from Harvard's affiliate female institution, Radcliffe College, Harvard wrote. (Women were accepted into Harvard only in 1977).

Payne-Gaposchkin discovered that the sun's atmosphere is mostly hydrogen, which went against the established thinking of the time that the sun and the Earth shared a similar composition. Payne-Gaposchkin went on to become the first female full professor in Harvard's faculty of arts and science, then the first female chair at Harvard – in astronomy.

Pickering appointed Cannon curator of astronomical photographs in 1911, although the Harvard president of the time wouldn't let her be put in the staff catalog. Her appointment was finally made official in 1938. She won multiple awards for her work before retiring in 1940. She died in 1941.

The photography plate collection program at Harvard continued until 1992, except for a shutdown for a few years in the 1950s known as the "Menzel Gap" (after its director at the time, who stopped it due to budgetary concerns). By the 1990s, photographic plates were rapidly being supplanted by more advanced technologies, such as the CCDs that are commonly used in digital cameras today. The plate archive, however, remains available for astronomical research and is also being digitized.

Additional resource

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.